Genes are not just honest faces that bring delightful news. Some are the footprints of epidemics and human cruelty, while others dispel theories into the depths of new mysteries. DNA can get downright disturbing when it comes to its origins and how it affects the human mind.

10 Mysterious Tame Horses

The first domesticated horses remain a mystery. The prevailing belief was that 5,500 years ago in Kazakhstan, a few animals were lassoed and made to wear a saddle. Horsemanship among the Botai culture, the people credited with horse domestication, is not a fallacy. Ancient remains at Botai locations include equine teeth of animals that wore some sort of bridle and fat from horse meat and milk. These animals were thought to be the first tame herd. But recent DNA tests of 88 ancient and living horses shattered two beliefs. The first proved that modern animals carried too little Botai influence to have come from Kazakhstan. This, in turn, revealed an unknown domesticated ancestor stock. For the time being, scientists cannot even guess their particulars. The second belief involved Earth’s last remaining wild horses—Przewalski’s horses. The Mongolian breed was thought to have originated in the wild, but the results showed they never did. Instead, they sprang from the already-domesticated Botai herds before turning feral. Interestingly, the DNA also revealed that the Botai horses had fetching white coats with spots.[1]

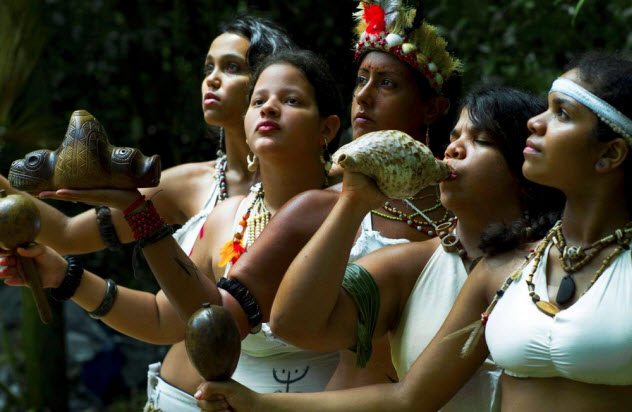

9 An Exiled Nation That Stayed

Before the Spanish destroyed the Inca, the Inca told the Spanish how they destroyed the people of Chachapoyas. The latter resisted the Inca when they invaded the Chachapoyas region of Peru. According to Spanish records, the locals were driven from the area in the 15th century. But in 2017, scientists took samples from people in Chachapoyas and found the Inca claim to be a bit gilded. Among those who had their DNA pinched and poked were living descendants of the Chachapoyas. The Inca may have conquered but did not scatter the Chachapoyas people completely. Another unusual trait appeared in the study. The Chachapoyas population remained genetically distinct, suggesting a refusal to intermingle with the Europeans or the Inca. The genetic tests came after a linguist traveled to Chachapoyas and found a few individuals still spoke Quechua, a language thought to be extinct locally.[2] Quechua, spoken by millions elsewhere, existed before Columbus arrived. The rare Chachapoyas dialect most closely matched Quechua from Ecuador. However, DNA showed no mutual link that could explain this.

8 Great-Great-Grandson Of Neanderthal

When an ancient human bone was discovered in Romania, the man’s ancestry was interesting. Named Oase 1, the jawbone was unearthed in 2002 from one of the Pestera cu Oase caves. The genome rescued from the relic was incomplete but enough to show nearly 10 percent of Neanderthal DNA. Today, people always measure beneath 4 percent. This made Oase 1 an unprecedented individual. That humans and Neanderthals interbred is well-known. But when and how much are elusive points. The man, who lived thousands of years ago, showed that the interspecies romance started soon after humans arrived in Europe. This development was not only unexpected but also killed the theory of a later merger. Either way, the ancient Romanian is a rare find—somebody genetically close to the phenomenon. With that much foreign genome, he could have had a Neanderthal ancestor as early as a great-great-grandparent. Oase 1 is as extinct as somebody can be. The Neanderthals bowed out as a species 39,000 years ago, and his human lineage has no match among the living.[3]

7 The Agent Behind Cocoliztli

Between 1545–1550, Mexico and Guatemala lived in fear. A devastating illness, eventually referred to as the cocoliztli epidemic, claimed countless lives. Suspicious historians turned to the Spaniards, who landed in Mesoamerica right before the outbreak. The natural assumption was that Spanish ships had brought a disease to which locals had no resistance. To see if the stowaway was smallpox or measles, scientists recently visited a Mexican cemetery that was abandoned after the epidemic. Located in Oaxaca, remains from 29 graves were analyzed by software, particularly to search for any germ DNA. Surprisingly, there was no trace of the usual suspects. Instead, it identified the deadly Salmonella bacterium in 10 individuals. The bug’s genome was reconstructed, and it turned out to be the subspecies S. paratyphi C. This type brings enteric fever, which includes typhoid. Salmonella poisoning is spread through infected food and water. Globally, an estimated 222,000 typhoid-related deaths are reported each year. The 10 ancient patients are the first evidence of Salmonella from the New World and a rare chance to observe the history of the disease.[4]

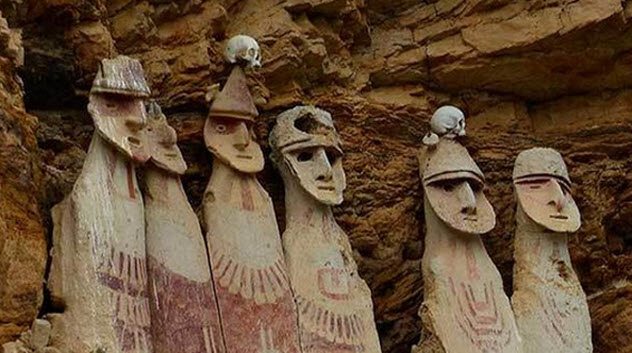

6 Taino DNA

European explorers are no longer blamed for the cocoliztli epidemic. The Caribbean is a different story. In the 15th century, Christopher Columbus parked his ships and the indigenous inhabitants, known as Tainos, suffered greatly. Those who were not carted off as slaves faced first-contact epidemics and wholesale slaughter. The impact was so severe that modern historians declared the Taino population extinct. This sidelined many people who live in the Caribbean. They stuck up their hands and said, “Hey, living Tainos right here.” To settle matters, DNA was required from an islander who lived before Columbus arrived. In 2018, a study proved that the Caribbean people did not imagine their heritage. From the Bahamas came the tooth of a woman who had died a thousand years ago, which made her the perfect candidate. Her undeniable Taino DNA matched living populations in the Caribbean, most commonly in Puerto Rico.[5] Apart from proving they survived, the woman’s genes also suggested that their roots came from South America and that their communities remained interconnected. This explains why no inbreeding was detected, something scientists expected from her small home island.

5 The Minoans’ Ethnicity

About a century ago, Sir Arthur Evans went to the island of Crete. There, the archaeologist found the breathtaking Minoan palace of Knossos. When Evans noticed the Egyptian-resembling art, he speculated that the Minoan culture had originated in Africa. The idea stuck. A lot about the Minoans remain mysterious, but they are credited with the first advanced civilization in Europe (2700 BC–1420 BC). In 2013, researchers dusted off a few Minoan skeletons and harvested their 4,000-year-old DNA. The samples were then compared to individuals from Africa and all over Europe, both ancient and still breathing. However, the results killed the long-standing Evans theory. The Minoans were not from Egypt or elsewhere in Africa. They were European. In the past, they most resembled Stone Age Europeans. The living population most similar are the islanders of Crete. Among them, the closest were from the Lassithi Plateau where the skeletons were found.[6] This proved that the Minoans were homegrown. They definitely had contact with Africa, which explains how the Egyptian flavor crept into their art.

4 Matriarchs Of Chaco Canyon

In the dry southwest of North America, another mysterious culture flourished. Between AD 800–1130, they built impressive homes in Chaco Canyon. Several discoveries returned life to the long-gone people, but researchers still lack the complete picture. To make things more difficult, the society was remarkably complex. Previous finds showed that the Chaco inhabitants had an elite class, but little was known about how an individual achieved such status. The biggest building, Pueblo Bonito, harbored a crypt with nine people who, in life, had dwelt in the upper crust. Their bodies accumulated over 330 years (AD 800–1130). In 2017, their genetic material was sequenced in the hope of understanding what set them apart as elites. A revealing link surfaced.[7] They were family and shared identical mitochondrial DNA, 37 genes passed on only by the mother. The elite group’s sequential generations represented an unbroken female line. For this reason, researchers believe the dynasty that ruled Chaco inherited power exclusively through the mother.

3 Death Of A King

In 2013, a journalist won a grim lot at auction—several old leaves stained with blood. Many gory relics are linked to the famous. In this case, it was King Albert I, an enthusiastic mountaineer. In 1934, the Belgian monarch fancied a mountain near a village called Marche-les-Dames. The 58-year-old set off alone, and his body was eventually discovered at the bottom of a cliff. The king was popular, and souvenir hunters descended on the place where he died. The area was stripped bare. In 2016, the journalist who purchased the leaves had them tested. DNA was provided by two living family members of Albert I—the German baroness Anna Maria Freifrau von Haxthausen and another king, Simeon II of Bulgaria. It was a match.[8] The authenticity of the blood was established, but the cause of death will likely never be known. Rumors of assassination wrestle with claims of an accident or suicide. However, the presence of blood disproved one conspiracy theory—that the king was murdered elsewhere and later moved by his killers to where he was found.

2 Cheddar Man

There is nothing cheesy about Cheddar Man. In fact, his face is rather startling. The skeleton was found in 1903 at Cheddar Gorge. He died young—in his twenties—but 10,000 years later, he represents Britain’s oldest human remains. Given that fact, researchers were curious to meet this “first citizen” and, in 2018, decided to reconstruct his skull. Taking it a step further, they also analyzed his genome to add eye and skin color. The ancient Briton’s DNA revealed a vivid contrast between the two. He had blue eyes set in a face that was dark brown to black. Cheddar Man’s hair was also dark with a slight curl. Modern beholders are bound to stare. But during his lifetime, the man’s looks were commonplace in western Europe. A landmass connected Europe with Britain, and Cheddar Man likely came from migrants who resettled the island 11,000 years ago. This population was eventually absorbed by pale-skinned farmers thought to have arrived 6,000 years ago from the Middle East. Interestingly, when his mitochondrial DNA was compared with people living in Cheddar village today, a match turned up in two residents.[9]

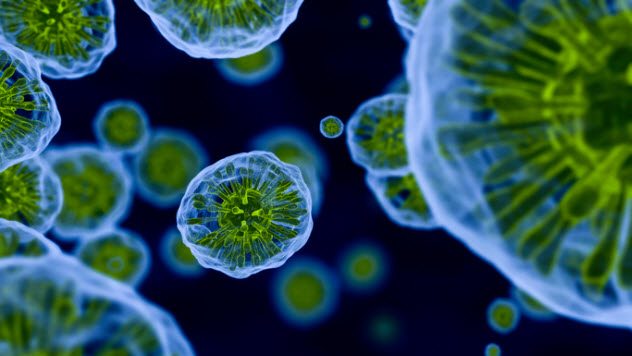

1 The Mind Virus

A study published in 2018 held some disturbing news—humans may have to thank a virus for conscious thought. This may seem groundless to begin with, but between 40–80 percent of the human genome consists of DNA left behind by archaic viruses. This process is usually harmless and even beneficial. Viral genes play a critical role in human embryo development and the immune system. The showstopper is the Arc gene. This genetic parasite, or virus, climbed into the brains of four-legged animals a long time ago. It merged its code with the host genome and remains active in human brains today. When a synapse fires, Arc mails its genetic information between nerve cells. The very act is viral, and the packages it sends around also resemble viruses. It is not known how Arc invaded people and animals or what happens once its genetic “mail” enters another cell. But Arc’s behavior maintains both communication between nerves and how they adapt, processes which are at the root of conscious thought. It may sound creepy to have a living ancient virus in one’s brain. But without it, synapses shrink and cognition is affected. When defective, the Arc gene has been connected to neurological disorders, including autism.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages