In the early 1990s the Mexico City government decided it was better for children born in prison to stay with their mothers until they were 6 rather than to be turned over to relatives or foster parents. The children are allowed to leave on weekends and holidays to visit relatives. A debate continues among Mexican academics over whether spending one’s early years in a jail causes mental problems later in life, but for the moment the law says babies must stay with their mothers. In Ohio they are trying a program called The Achieving Baby Care Success program. It began in June 2001. The 12 mothers currently participating live in a special wing of the prison. The babies sleep in identical cribs in their mothers’ cells. Between prison roll calls, mothers take their children to the in-house nursery for scheduled activities.

Victim-offender mediation, or VOM (also called victim-offender dialogue, victim-offender conferencing, victim-offender reconciliation, or restorative justice dialogue), is usually a face-to-face meeting, in the presence of a trained mediator, between the victim of a crime and the person who committed that crime. The victim gets to explain how they feel and felt, and what needs were not met as the result of the action of the offender. The offender is to repeat what he or she hears (i.e. feelings and needs) and continue to listen and repeat what the victim says she or he feels and needs. Usually this requires substantial support from the trained mediator to gain clarity about the feelings and needs and to request the offender to say these words back to the victim. Once the victim feels completely heard he or she is then ready to listen to what the offender feels and needs now and felt and needed at the time of the crime, and the victim, if he or she has been heard adequately will be ready to hear and reflect these feelings and needs back to the offender. Usually the session ends with a request from the victim to the offender, and from the offender back to the victim. The requests lead to a strategy for resolution. Pictured is the VOMA administrator Barbara Raye.

In the 1980s, boot camps as alternatives to juvenile prisons came in style. New Orleans parish opened the first one in 1984; within a few years, there were several hundred in thirty-three states. Typically, those eligible were young non-violent offenders who were facing long prison terms. They could exchange a three-to-ten year term for thirty to 180 days in boot camp. The public liked the idea of boot camps as a wholesome, effective alternative to prison. State legislatures liked the millions of dollars that the camps saved in prison spending. Some camps offered job training and high school classes along with substance abuse treatment. The states called the camps “modern shock incarceration.” Almost immediately, thousands of stories of abuse and maltreatment began to circulate in the press. Over three dozen inmates died. One horrific case occurred in Florida on January 5, 2006. A boy named Martin Anderson died within the first three hours of admission to the Florida Bay County Sheriff’s Boot Camp. After Martin collapsed after failing to run a 1.5-mile lap.

As an unprecedented number of ex-offenders is expected to be released from the nation’s prisons in coming years, corrections officials are looking for innovative ways to increase the chance that fewer of them will return. Many officials have turned to religious programs that seek to change inmates’ internal motivations as well as external behaviors. The Bush administration has strongly supported such programs, as a key focus of its Faith-Based and Community Initiative, an effort to encourage religious charities and other nonprofits to provide social services. The biggest experiment in religious prison programs may be in Florida, which operates three “faith and character-based institutions” – entire prisons that provide religious programming aimed at rehabilitation. More commonly, programs are dedicated to units within a prison, or prisoners receive help from volunteer mentors coordinated by faith-based groups.

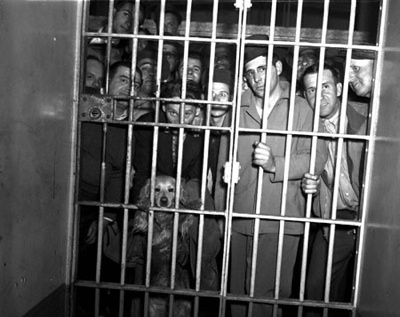

Inmates residing at the Shimane Asahi Shakai Fukki Sokushin Center (Shimane Asahi Social Rehabilitation Promotion Center) in Japan, will be participating in a program in which they will help train guide dogs for the blind, by having inmates raise the puppies with classes on dog-walking and obedience training. Similar programs are currently operating all over the United States, and these types of programs have been proven to reduce violence among inmates and foster a sense of responsibility.

From literacy to GED preparation to vocational education programs, prisons have historically attempted to offer at least some basic education to inmates in prison. Skeptics claim that, in many cases, prison education produces nothing more than “better educated criminals”. However, many studies have shown significant decreases in recidivism. A study by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Prisons found: “The more educational programs successfully completed for each six months confined, the lower the recidivism rate.”

A conjugal visit is a scheduled extended visit during which an inmate of a prison is permitted to spend several hours or days in private, usually with a legal spouse. While the parties may engage in sexual intercourse, the generally recognized basis for permitting such a visit in modern times is to preserve family bonds and increase the chances of success for a prisoner’s eventual return to life outside prison. In the United States, inmates must meet certain requirements to qualify for this privilege, for example, no violation of the rules in the last six months, history of good behavior, and so on. Those imprisoned in medium or maximum security facilities and inmates on death row are not permitted conjugal visits. New York, California, Mississippi, Washington, Connecticut, and New Mexico are the only six states that currently allow conjugal visits. There are strict rules and requirements, from behavior to sexual orientation and disease status. France and Canada allow prisoners who have earned the right to a conjugal visit to stay in decorated home-like apartments during extended visits. In Brazil, male prisoners are eligible to be granted conjugal visits for both heterosexual and homosexual relationships, while women’s conjugal visits are tightly regulated, if granted at all.

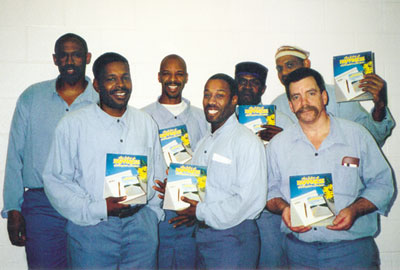

Prison contemplative programs are classes or practices — including meditation, yoga, contemplative prayer or similar —that are offered at correctional institutions for inmates and prison staff. There are many stated benefits of these programs – such a stress relief for inmates and staff – and some measured and anecdotally reported benefits in studies. These programs are gaining in acceptance in North America and Europe but are not mainstream. These programs may be part of prison religious offerings and ministry or may be wholly secular. Of those sponsored by religious organizations some are presented in non-sectarian or in non-religious formats. Contemplative practices in prison date back at least to Pennsylvania prison reforms in the late 18th century and may have analogs in older correctional history. In North America, they have been sponsored by Eastern religious traditions, Christian groups, new spiritual movements such as the Scientology-related Criminon prison program, as well as interfaith groups. Pictured above are members of the Scientology cult prison program Criminon.

Drug-dependant individuals are responsible for a disproportionately large percentage of violent crimes and property offenses, committing about half of all felonies in big U.S. cities. According to the National Institute of Justice’s Arrestee and Drug Abuse Monitoring report, roughly two-thirds of adults and more than half of juveniles arrested test positive for at least one illicit drug. A third of state prisoners and about 1 in 5 federal inmates said they committed their offenses while under the influence of drugs. Many of them turned to crime for money to support expensive drug habits. Three-quarters of chronic cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine users are arrested in the course of any given year, and only a quarter of these people received drug treatment in the past. Most return to drugs as soon as they complete their prison terms. In turn, drug abusers constitute half the people on probation and parole in America. Because so many drug addicts become involved with the criminal justice system — and take up a significant portion of America’s law-enforcement and corrections budget — prisons are a natural place to offer drug treatment. Studies prove that when people are forced into therapy, results are positive. Unfortunately, only a small proportion of inmates requesting drug treatment currently are helped. Without effective intervention, we are merely postponing the time when prisoners return to drugs and crime.

The Honor Program, conceived by prisoners and non-custody staff at a prison in California has been operating since 2000. Based on the principle of incentivizing positive behavior and holding individuals accountable for their actions, the purpose of the Honor Program is to create an atmosphere of safety, respect, and cooperation, so that prisoners can do their time in peace, while working on specific self-improvement and rehabilitative goals and projects which benefit the community. Prisoners wishing to apply for the program must commit to abstinence from drugs, gangs, and violence, and must be willing to live and work with fellow prisoners of any race. In its first year of operations, there was an 88% decrease in incidents involving weapons and an 85% decrease in violent incidents overall on “A” Facility; the Honor Program saved the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) over $200,000 during the first year alone in costs related to the management of violent and disruptive behavior. In its six years of operation, it has saved the California taxpayers hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars. Contributor: rushfan