The frosty wonder can also move in nanoseconds, hide things for millions of years, and become the material of choice in a nuclear disaster. Ice is celebrated in a big way all over the world—from China to Norway, where festivals bring out the true splendor and weirdness of this natural wonder.

10 Long-Lasting Ice Pop

A hot day can melt an ice pop so fast that you end up licking your hand more than the snack. In 2018, a British firm announced the answer. They called it the world’s first “non-melting ice lolly.” In truth, it does melt. To be more positive, it lasts hours longer than ordinary ones. The company, Bompas & Parr, is known for quirky foodstuffs like flavored fireworks. Their solution to the irritating ice pop drip was clever. In World War II, Geoffrey Pyke invented pykrete, ice that contains wood pulp and sawdust. Pike envisioned that aircraft carriers could be build from the material. Winston Churchill supported him. But when the project cost too much and was shut down, Pike committed suicide. He could not have foreseen his invention’s influence on the non-melting lolly. The pykrete inspired the snack’s main design for heat tolerance—strands of fruit fibers. Although it sounds simple, the ice pop took a year to develop and was rolled out to the public in apple flavor. Thanks to the fiber content, this ice pop is a little more chewy than ordinary ones.[1]

9 The Giant Spinning Disk

In Maine, winter 2019 left a treat in the Presumpscot River. Near a bend in the river churned a disk of ice. It was hefty, measuring 100 meters (330 ft) in diameter. Slowly spinning in a counterclockwise direction, the swirl was unusual but not unique. The right circumstances will spawn one right there and then. A large eddy, usually where a river kinks, traps pieces of ice. The one in Maine probably began with ice fragments tracing the egg-like rotation of the eddy. As pieces kept arriving from upstream, the swirling and knocking against the shoreline crushed the ice together. It froze into a solid plate. As it kept turning with the eddy and chafed against the banks, the disk became circular.[2] Presumpscot River likely has produced similar ice wheels in the past, and in 1993, the same thing happened in North Dakota. The Sheyenne River produced a disk (smaller than the one in Maine) when ice collected at an eddy.

8 Destruction Of Larsen B

Larsen B was an ice shelf in Antarctica. Noteworthy for its stability, the structure was around 10,000 years old. In 2002, it collapsed within weeks. Around 3,250 square kilometers (1,250 mi2) of ice tumbled into the sea, the first time that this volume had vanished so quickly. The only clue was a dramatic one. Over 2,000 lakes had sprung up all over the shelf during the months before. These meltwater lakes are normal for the summer season when ice melts and collect in basins. As one reservoir can hold over a million tons of water, researchers wondered if their combined weight caused Larsen B to break apart. In 2016, the theory was tested. With melt season approaching, several basins on the McMurdo Ice Shelf were rigged with measuring equipment. The data showed that lakes filling with melt caused the shelf to bend.[3] McMurdo survived the season. But during a hypothetical test, the shelf “broke” when the lakes were slightly bigger and closer together. This was pretty much the smoking gun for Larsen B.

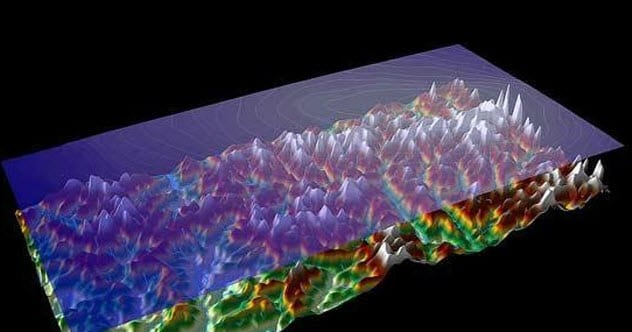

7 Frozen Mountain Range

Antarctica’s biggest mountain range is the Gamburtsevs. It’s about the same size as the European Alps, but nobody had ever seen the giant in the flesh, so to speak. The whole thing is covered by a layer of ice as thick as 3,050 meters (10,000 ft). The frozen blanket is why the 100-million-year-old mountains look baby fresh. At that age, they should have been severely eroded. This natural process probably hit a pause button when ice enveloped the region, including the then-young Gamburtsevs. During a four-week project that ended in 2009, scientists zipped over the range in planes. Radar measured everything below and revealed a stunning geography. The mountaintops were 2,700 meters (8,850 ft) above sea level. Deep valleys flowed with rivers and lakes. Curiously, at certain points, the water flowed uphill. Heavy pressure from the ice overhead helped the liquid to move against gravity. At higher elevations, however, the water froze and provided the layer of ice that preserved the Gamburtsevs.[4]

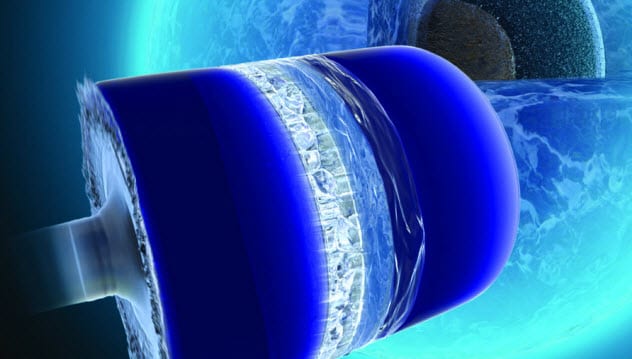

6 Fukushima’s Ice Wall

In 2011, an earthquake and tsunami wrecked a nuclear plant in Japan. The consequences continue to this day. One of the worst is water contamination. In 2017, the government devised a plan to stop radioactive water leaking from the Fukushima plant from reaching groundwater. They constructed an underground wall made entirely of permafrost. Running 30 meters (100 ft) deep and 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) long, the project cost $320 million.[5] From the start, the ice barrier has had its critics. Soon, it became obvious that the wall slowed down the contamination, but it did not seal anything. Radioactivity continued to contaminate a frightening 500 tons of water every day. The good news was that about 300 could be pumped out to be purified. Before the ice wall was installed, the daily amount was worse. However, the venture remains expensive. The permafrost hedge requires $9.5 million per year to maintain. For now, it remains the best solution for a plant so irradiated that not even robots can enter to clean up the uranium trapped inside.

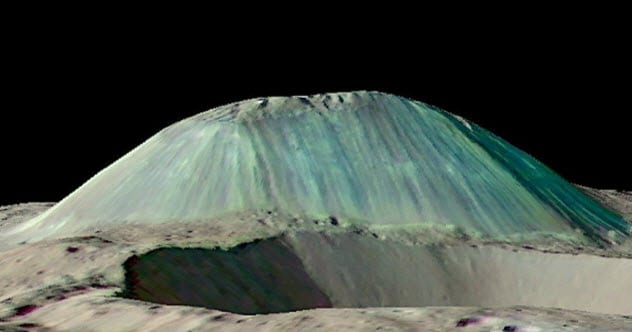

5 Ice Volcano

Ceres is an odd duck. From the 1800s to modern times, astronomers changed its classification three times. It was discovered as a planet and then demoted to an asteroid before its recent upgrade to a dwarf planet. This chameleon is noteworthy for something else—the first evidence of cryovolcanism. This occurs when volcanoes made of ice spew boiling salt water instead of hot lava. Scientists suspected that cryovolcanoes existed in the solar system, but they had never found one. In 2016, NASA’S Dawn spacecraft investigated the 965-kilometer-wide (600 mi) Ceres. Of particular interest was Ahuna Mons, a massive mountain standing 3,962 meters (13,000 ft) tall and measuring 17.7 kilometers (11 mi) wide at the base. Finding such a gargantuan cone on a small planet was weird. Even stranger, it stood alone. But the shape and the isolation were healthy signs of a volcano. (Only volcanic activity can create lone mountains.) To boot, Ahuna Mons was made entirely of ice. It even had a volcanic dome, flanks, and summit similar to Earth’s volcanoes. Everything points to Ahuna Mons being the first recorded cryovolcano.[6]

4 Ice Instruments

The 2018 Ice Music Festival in Norway happened on a stage carved entirely from ice. Musicians also played instruments fashioned from the frozen waters of Lake Finse as well as a local glacier. Things like drums, woodwinds, guitars, trumpets, and harps are made to resemble—and sound like—the real things. The festival also created the world’s first ice double bass and saxophone with two openings. As far as music goes, people are often surprised by how similar the ice instruments sound to traditional ones. The most notable difference is volume. The frosty pieces whistle, thump, and toot in softer tones. Musicians also face an unusual challenge. Playing with gloves hampers the quality of the music, so none are worn. Handling an ice guitar in extremely cold conditions is enough to suck the feeling from anyone’s fingers. During a performance, musicians take turns to warm their hands or play. The most mysterious fact about the ice instruments concerns their origins. When carved from natural ice, they produce musically accurate sounds. Instruments that come from artificial ice (the freezer type) have no acoustic properties.[7]

3 The Harbin Festival

Every winter, China hosts a spectacular festival. The theme is all about ice. In 2019, 10 million visitors were expected to arrive at the 35th annual Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival. For two months, people explored massive ice and snow sculptures. They included buildings like castles and the Colosseum constructed with giant ice bricks. However, the real magic happened at night. The replicas were lit from inside with different colors, giving a fantasy feel that almost distracted tourists from the extreme cold. There was no chance for sightseers to get bored. The ice creations covered 743,000 square meters (8 million ft2) of the city of Harbin. Building the wonderland required around 113,000 cubic meters (4 million ft3) of material. This achievement was made within days by an army of workers in the thousands who carved the large blocks. Apart from the icy architecture, the festival also hosted subzero swimming, mass weddings, and snow sculpture competitions.[8]

2 Green Icebergs

The Southern Ocean has a lot of icebergs, but some of them are green. Impressively green. Scientists first boarded one in 1988 near East Antarctica. More surprising than the color was the clarity. The ice looked like solid glass without bubbles. This type of ice hails from ancient glaciers, but those are usually blue. At first, the green wonders seemed like a quirk of nature. When researchers searched for the reason behind the hue, it became clear that the icebergs could play an important role in dispersing ocean nutrients. The green ice did not come from glaciers on land. Instead, they calved from the undersides of floating ice shelves. A recent study found that the Amery Ice Shelf (where the 1988 iceberg was found) was packed with iron. The iron came from rocks crushed into a powder as glaciers snailed over them. Eventually, they end up in shelves and oxidize in seawater.[9] Iron oxide particles turn green when light shines through them. The icebergs probably disperse iron to phytoplankton, helping them survive in remote places where they normally could not.

1 Ice VII

In 2018, the world’s quickest ice was found inside diamonds. Discovered deep underground, Ice VII grows at over 1,600 kilometers per hour (1,000 mph). Laboratory tests revealed a few characteristics about the speedy stuff. It formed when high pressure and temperatures were both present. The ice could also freeze almost all at once or work its way down from the surface. The two variations confused scientists until they discovered that Ice VII does not freeze water in the usual way. Normally, heat must be reduced before a liquid can turn solid. This makes ice expand slowly as it cools its way into growth. Ice VII first blooms inside molecule clusters. This bypasses the heat problem, allowing the ice to spread in nanoseconds. Whether it explodes all over the place or works downward from the surface depends on temperature differences between the water and ice crystals.[10] This type of ice could help to find extraterrestrial life, ironically by eliminating the dead worlds. The pressure needed to create Ice VII is several thousand atmospheres—too much to allow life. Any alien world with this kind of pressure is likely to be barren. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages

![]()