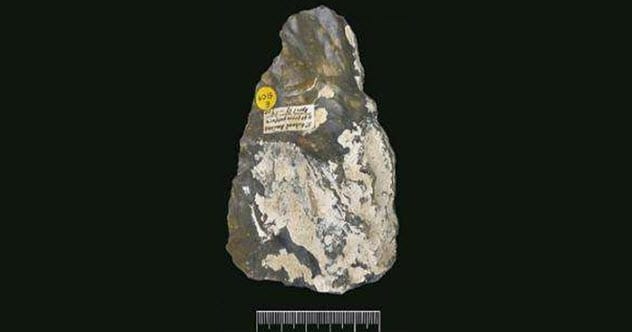

10 The Prestwich-Evans Axe

One flint tool changed scholars’ view of human evolution. In 1859, French miners found a hand axe. A pair of geologists, Joseph Prestwich and John Evans, took an interest and made the historical move of photographing an artifact before removing it from its original position. At that time, experts believed that humans had been walking the Earth for only a few thousand years. However, the axe was discovered among woolly mammoth and rhino fossils. This was the first solid evidence to push back humanity’s origins[1] to a couple of thousand years earlier. Today, the tool is believed to be around 400,000 years old. Other discoveries would eventually eclipse its age. For example, the oldest-known tools were unearthed later in Ethiopia and dated to around 2.5 million years old. But the Prestwich-Evans axe holds the honor of having broken the assumption that mankind was young and didn’t undergo evolution. After Prestwich died in 1896, the axe was included in his collection of artifacts that was donated to the Natural History Museum. In 2009, researchers rediscovered the specimen in storage and put it on display.

9 Unique Mummy Shroud

The National Museum of Scotland was busy reassessing their Egyptian collections when a senior curator found something. Sitting unopened for nearly 80 years was a paper package. It had been wrapped in the 1940s with a note mentioning that the contents originated from a tomb in Egypt. The parcel held a piece of textile. Since it hadn’t been unfolded in ages, the fibers were fragile and dry. To prevent breakage, the cloth was humidified and painstakingly opened. It took conservators nearly 24 hours to spread the material. During the process, the team began to suspect that it was a body shroud as they saw more painted details. Once fully opened, it beat every expectation[2] in the room. The artifact was indeed a funerary shroud and represented the person it had once wrapped as the god Osiris. The stunning painting was done in a style that was hard to place, similar to Roman-period Egyptian art but not quite. Hieroglyphics named the deceased as an unknown son of Montsuef, an important official who died in 9 BC. This makes his son’s unique shroud over 2,000 years old.

8 Trajan’s Unknown Statue

A statue of Roman Emperor Trajan (r. AD 98–117) received a raw deal from the moment it was discovered. During the 1980s, the bronze figure was recovered from a Roman fortress in Bulgaria. Candidiana existed from the second to the seventh centuries as part of a series of Roman stations connected by a road along the Danube in the North. Despite the statue’s elaborate decorations and worth, it was never made public. It was also badly fractured, perhaps by the barbarian attack that destroyed Candidiana. The pieces were taken to Bulgaria’s National Museum of History and forgotten.[3] For decades, the pieces were kept on the floor of the laboratory between other statues and artifacts. In 2016, somebody took notice of the shattered emperor and realized that the artwork was still unknown to the outside world. The motifs covering the surface were also rare, showing scenes from mythology that included heroes and gods of antiquity. Unfortunately, the museum has neither the funds to restore the statue to its original glory nor the space to display it.

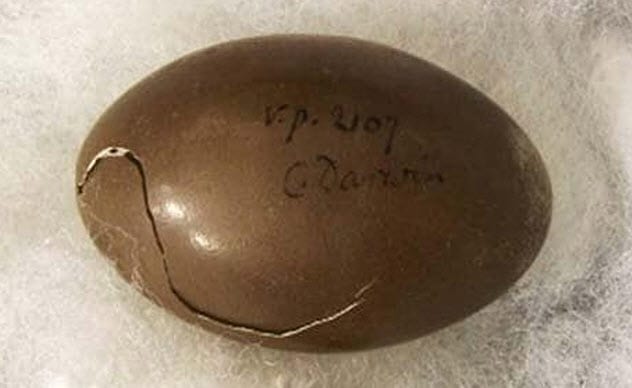

7 An Egg From The Beagle

The ship that carried Charles Darwin on his famous specimen-collecting voyage was called the HMS Beagle. The naturalist’s trip lasted from 1831–36, and among his acquisitions were 16 chocolate-colored eggs from modern-day Uruguay. The entire clutch was believed to have been lost. Meanwhile, volunteer Liz Wetton single-handedly cataloged the egg collection at Cambridge University’s Zoology Museum. Since she only worked a few hours a week sorting through thousands of eggs, it took her 10 years to reach one dark-brown specimen. On it was written “C. Darwin,” and the shell had a ragged crack.[4] Wetton thought the museum was aware of the egg, but nobody knew it was there. Curators traced its origins back to the Beagle with the help of 19th-century zoology professor Alfred Newton, who had been a friend of Darwin. Newton had written about Darwin sending him an egg belonging to the common tinamou. Remarkably, the notebook also revealed how the shell had broken. Darwin had packaged it in a box that was too small, and the shell was damaged during or after the voyage.

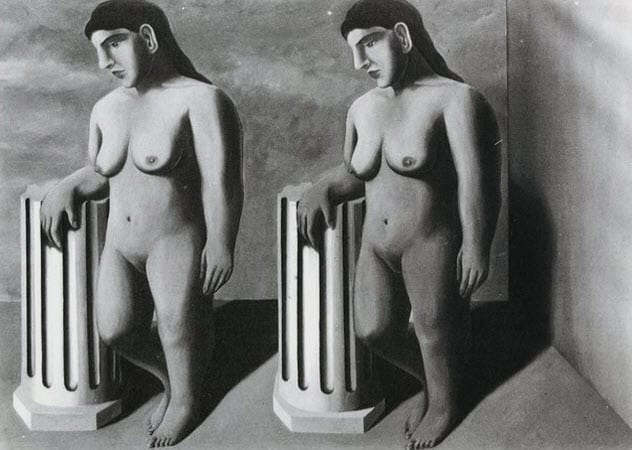

6 Pieces Of The Enchanted Pose

Belgian painter Rene Magritte is best known for his surrealist art. After an exhibition in 1927, one of his paintings vanished. The 114-centimeter (45 in) by 162-centimeter (64 in) canvas, named The Enchanted Pose, depicted a pair of neoclassical female nudes. When the work didn’t sell at the exhibition, it was returned to Magritte. After that, the trail went cold.[5] In 2013, the art world finally received a clue about what had happened to the painting. While scanning two of Magritte’s other works, experts found a quarter of The Enchanted Pose underneath each. These works were from museums in New York and Stockholm and together formed the complete left side of the missing painting. A third piece was discovered in 2016 when a conservator at the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery noticed a previously used canvas beneath another Magritte painting. An X-ray revealed the bottom-right corner of The Enchanted Pose. It appears that Magritte needed canvas for his new work, so he cut up the old. Somewhere out there, the upper-right section is still hiding.

5 Unexpected Human Remains

At the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, a display case regularly attracts visitors. Inside is a 150-year-old arrangement of lions attacking a man and his dromedary. During recent renovations, the stuffed animals were discovered to still retain parts of their skeletons. A CT scan of the mannequin revealed additional bone that was even more gruesome. The head contained a real human skull with its teeth intact. This came as a shock because the life-size figure was thought to be entirely synthetic. A look into its history revealed a shady pair who had committed this sort of act before. In 1830, French naturalist Edouard Verreaux and his brother shocked society when they stuffed an African tribesman. In the mid-1800s, Edouard was also the taxidermist who created the lion-dromedary display, which was owned by several museums before landing at the Carnegie in 1898. The skull can’t be returned to the person’s homeland since no record exists of where the Verreaux brothers acquired it. Such records might be a hindrance anyway as the brothers regularly falsified information[6] to ensure more sales.

4 The £3 Million Masterpiece

Around 150 years ago, the Swansea Museum cataloged an oil painting as the work of an unidentified artist before storing it. When it was found in 2016, an art historian recognized the style of the 17th-century Flemish painter Jacob Jordaens. On the back of the painting, a merchant’s marks that included the letter A and the coat of arms of Jordaens’s hometown, Antwerp, confirmed that the panel was manufactured between 1619 and 1621. Once a student of Peter Paul Rubens, Jordaens became famous in his own right. But this was not just another recovered painting from a master. It was a previously unknown test run of what would later become one of his most celebrated creations, Meleager and Atalanta. This makes it exceptionally rare. The picture was a bit of a painted-over mess, but restoration soon revealed a stunning scene where the mythical pair was surrounded by horses, dogs, and people. The painting adds to what is known about Jordaens’s methods and is worth a heady £3 million.[7]

3 Dead Archbishops

In 2016, the Garden Museum in London renovated a floor when workers discovered a removable concrete block. Shifting the slab revealed steps leading down to a mysterious room. One of the first things the crew saw was an archbishop’s miter resting on top of a coffin. Overall, there were 20 caskets. Nameplates and a search of the building’s history revealed that five coffins belonged to former archbishops of Canterbury. All held this position during the 17th century, and the most illustrious was Richard Bancroft. Archbishop from 1604–1610, he played a critical part in establishing the King James Bible. The museum used to be the St. Mary-at-Lambeth Church and stands near the London residence of the archbishop of Canterbury. Despite this, the crypt’s presence was still a huge surprise. To build one so near the Thames courted a proper flooding.[8] Also, during Victorian times, hundreds of coffins were removed to clear the grounds. But somehow, the high-status group in the hidden tomb was left behind.

2 Chalk Sketch Worth $10 Million

Sir Timothy Clifford, a scholar from Scotland, spent his sabbatical at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum in New York. While there in 2002, he riffled through a box of designs and found a black chalk sketch of a candelabrum. It was simply labeled as “Italian, circa 1530–1540.” Luckily, Clifford was an Italian Renaissance expert[9] and recognized that the picture, measuring 43 centimeters (17 in) by 25 centimeters (10 in), was done by none other than Michelangelo. Cooper-Hewitt had bought it along with the other boxed designs in 1942. For only $60. Before that, the dealers P&D Colnaghi had procured the chalk sketch in 1921 when Lord Amherst of Hackney’s collection was auctioned. At the time, the museum mistook the candelabrum sketch as the work of Perino del Vaga, a contemporary of Michelangelo. Perino had churned out design drawings while Michelangelo rarely had. However, the sketch has since been authenticated by other Renaissance scholars and valued at over $10 million. Clifford believes that the item was commissioned for the Medici tombs and would have stood around 2 meters (6 ft) tall if the crypt’s construction hadn’t been canceled after the sack of Rome.

1 The Mamluk Porch

An old letter in the Louvre’s archives alerted the museum to a forgotten wonder. The letter had been written by a curator from the Musee des Arts Decoratifs, another French institution, asking for assistance in identifying pieces in their possession as possible Islamic architecture. The curator mentioned a vaulted structure and included descriptive drawings and a lot number. The so-called Mamluk Porch[10] was transferred to the Louvre in 2004, numbering 300 separate blocks. Years of funding and research went into understanding its origins. In 15th-century Cairo, a Mamluk ruler built a chamber at the entrance of his home. The stones were from the walls and vault of this lobby. It was taken apart in 1887 and shipped to France for the World Fair two years later. Never exhibited, the stones were stored until the letter was found. Additional drawings made in Cairo by a French architect before the portal was dismantled helped with the reconstruction. The result was a breathtaking monument, 4 meters (13 ft) high, that was decorated with floral designs in different shades of limestone. The porch is also the first Mamluk building to be shown in any museum. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages