All the same, bank robberies are very real events in which people can (and do) lose their lives, not to mention the aftereffects on those who survive. The following list takes a historical look at both the early days of bank robbery in the United States as well as inexplicably bizarre and shocking heists that have been largely forgotten.

10 Reconstruction Era

During the Civil War, bank heists were not considered to be robberies but acts of war. Case in point: the St. Albans Raid, which was carried out in Vermont by Confederate soldiers in 1864. Such acts were viewed not only as revenge on the North but as strategic war tactics that pulled Union soldiers from the front lines while simultaneously lining the pockets of an impecunious Confederacy. That all changed on February 13, 1866, when a group of horsemen rode into Liberty, Missouri. On that snowy afternoon, ten to 13 “bushwhacking desperados” raided the Clay County Savings Association, leaving one college student dead.[2] In time, the James-Younger Gang would be implicated for the deadly heist, along with an innumerable amount of other fatal robberies. The heist has been noted as the first successful daylight bank robbery during peacetime in American history. As we will see, it most certainly wasn’t the first bank robbery, period. While Jesse James set his sights on anything and everything—banks, trains, stagecoaches, etc—former Confederate soldiers still held a passionate and unremitting disdain toward the North. This resulted in a series of robberies aimed at banks that held the funds of former Union soldiers. The Northfield Bank in Minnesota, for example, was specifically targeted due to their client Adelbert Ames, a despised former Union general.

9 Age Is Just A Number

In 2018, the Pyramid Federal Credit Union in Tucson was robbed at gunpoint by a career criminal the state of Arizona would not soon forget. The suspect, Robert Francis Krebs, is undoubtedly a rarity in his line of work, given his ripe old age of 80.[2] After serving more than 30 years in prison for a 1981 bank robbery in which two employees were left handcuffed in a vault, the geriatric bandit was destined to return to his favorite pastime. Surprisingly, the title for “America’s oldest bank robber” actually goes to J.L. Hunter “Red” Rountree, who committed his last heist in 2003 at the age of 91. He died in prison the following year. Though it’s safe to assume there is a scarcity of gun-wielding great-grandpas, there has been an increase in the United States of robberies conducted by minors. According to FBI statistics, nearly 18,000 boys and about 1,900 girls younger than 18 were arrested for robbery in 2008, amounting to a 38-percent increase in less than a decade. In 1981, a midtown Manhattan bank was robbed at the hands of a nine-year-old boy. In a risibly creative defense, the child’s attorney argued that he was influenced by television and that he was “only playing” when he aimed the toy gun at the bank teller: “Robert is a victim of shows that are on television, depicting violence and breaking the law.”

8 The Monk

The journey of one of Ireland’s most infamous criminals began at an early age. From jumping over counters in banks to racking up more than 30 convictions before his 18th birthday, Gerry “The Monk” Hutch is credited—albeit disputably—with pulling off two of the biggest heists Ireland has ever seen. In 1987, at the age of 24, Hutch and his crew robbed a Securicor van for £1.7 million, making him enemy number one for the Gardai (the state police force of the Irish Republic). Such a flattering title, however, did little to deter Hutch, despite the fact that the Gardai preferred shooting armed robbers as opposed to apprehending them. The Monk’s biggest score would come in 1995, when he made off with IR£3 million from Brinks Allied in Dublin. Throughout the years, the Gardai did everything in their power to capture Hutch, and even then, prosecuting the criminal mastermind seemed fruitless given the lack of evidence.[3] Eager for a conviction and with little to go on, the Criminal Assets Bureau (CAB) targeted Hutch for money laundering in 1999. Hutch eventually reached a settlement with the CAB. These days, he lives a more quiet life as a businessman with a taxi fleet and property interests.

7 Gladbeck

The Deutsche Bank robbery in Gladbeck will forever be the epitome of abysmal failure pertaining to the handling of a hostage crisis. It all began in West Germany on August 16, 1988, when Dieter Degowski and Hans-Jurgen Rosner held the bank’s employees captive in what has now become known as “The Gladbeck Hostage Drama.” Over the next three days, the antics of the murderous duo became a public spectacle with the help of eager reporters determined to make a name for themselves. The media’s extraordinary access to the crime in progress not only hindered police involvement but indisputably allowed the incident to escalate. While millions watched on television, the two men gave impromptu interviews as if they were movie stars, all while holding guns to the heads of their quivering hostages. Fifty-four hours after the start of the madness, Degowski and Rosner were in custody, while victims Emanuele di Giorgi, 15, and Silke Bischoff, 18, lay dead in the street.[4] One police officer had also been killed. It became evident, only after the horrifying end result, that the journalists clearly overstepped their boundaries. Their involvement and behavior were deemed “unethical,” spurring the German Press Council to rewrite their own guidelines. Due to this, reporters in Germany are no longer allowed to interview hostage takers, negotiate on their behalf, or intervene in any crime in progress—guidelines that were too little, too late for three people.

6 Hasty Getaway

At 10:30 AM on August 13, 1909, two men entered the Santa Clara Valley Bank armed with revolvers. Staring down the barrels of their guns, the cashier had no choice but to hand over $7,000 in gold to the unmasked bandits. Just as swiftly as they arrived, they were gone, out the front door and into an awaiting car. Nevertheless, the feeling of jubilation was fleeting, given that the automobile broke down 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) out of town. Taking off on foot, the two men and their getaway driver were soon overtaken by a posse led by the sheriff, chief of police, and a pissed off mob of citizens. That hot August morning in 1909 became the first bank robbery in which the culprits used an automobile as a means of escape.[5] Two years later on December 21, 1911, the Bonnot Gang would employ the automobile for their expedited route to freedom. The notorious band of anarchist murderers and thieves struck terror into the hearts of Parisians, killing anyone who stood in their way. Seeing as the automobile was a guaranteed method to elude authorities, who relied on horses, the men were determined to get their hands on a vehicle. Their opportunity arrived on a desolate open road far from society when a De Dion-Bouton limousine crossed their path. As mercilessly as was to be expected, the men executed both the driver and the passenger before heading into town to pull off the perfect heist. In spite of being pursued by authorities and locals much like in Santa Clara, the revving engine of the limousine, along with the Bonnot Gang’s firepower, allowed them their lives and freedom, both of which would be short-lived. This incident is considered the first successful use of a getaway car in a bank robbery.

5 16-Millimeter

With fantasies of getting rich, Steven Ray Thomas and Wanda DiCenzi calmly walked into the St. Clair Savings & Loan Co. with nothing but a measly, yet convincing, starter pistol. It was April 12, 1957, when Thomas, 24, and DiCenzi, 18, made off with $2,376 to an awaiting getaway car driven by 18-year-old Rose O’Donnell. The brazen holdup would have been nearly flawless, had it not been for the hidden 16-millimeter camera capturing the culprits on film for the world to see. Before then, surveillance technology was primarily for military use and unheard-of in public settings, thus making the crime the first bank robbery ever captured on film. Less than 24 hours later, the Cleveland bank heist became international news, with still shots of Thomas and DiCenzi plastered on the front pages of newspapers throughout the United States. In a panic, Thomas fled town, making it to Indianapolis before coming to the realization that his hopes of a successful escape were futile. Collapsing to the pressure of their inevitable capture, all three voluntarily surrendered to authorities within days of the robbery. Following Thomas’s sentencing in October 1957, headlines read “Star Gets 10-to-25.” Meanwhile, both women were given probation. Ironically, the camera that opened the door for a new kind of law enforcement had been installed the day before the robbery.[6]

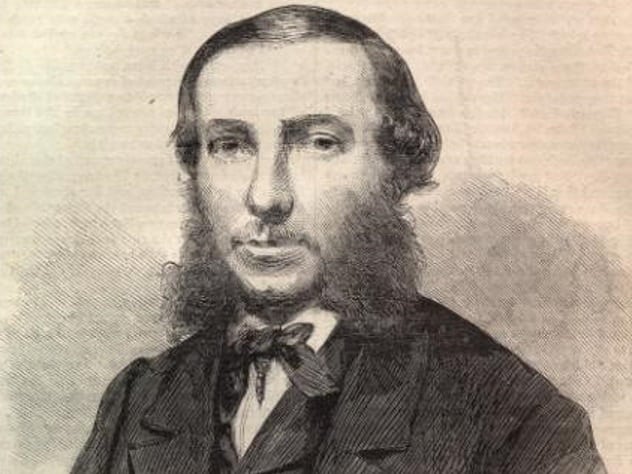

4 Edward Green

On December 15, 1863, in Malden, Massachusetts, a bitter drunkard with heavy debts walked into the Malden Bank to exchange a torn dollar bill for a new one. Noticing that he and the bank teller, 17-year-old Frank E. Converse, were the only ones present, Edward Green formulated a plan to end his financial troubles. Green returned home, retrieved his pistol, and immediately headed back to the bank. Without a moment’s notice, he raised his gun and shot the young man in the center of his head at point-blank range. Following the ruthless murder, Green made off with $5,000, spurring a nationwide manhunt. The crime would go unsolved for some time. By early winter the following year, locals took notice that Green had begun to pay off his debts. Chatter throughout the community ultimately led to an investigation. Authorities ascertained that he had paid off a two-year debt of $700. An examination of the bills Green used later revealed that they were from the Malden Bank, sealing his fate. Upon his arrest, Edward Green confessed to murdering the teenager and robbing the bank. Two years later, on April 13, 1866, the murderous drunk met his fate at the gallows, becoming the first armed bank robber to be hanged in the United States.[7]

3 False Imprisonment

On the night of August 31, 1798, an unbelievable sum of $162,821 was stolen from the Bank of Pennsylvania at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia. Police immediately suspected blacksmith Pat Lyon as the culprit, given that he had changed the locks to the iron vault the day prior. When word reached Lyon that he was the prime suspect, he immediately turned himself in to authorities in order to clear his name. During a lengthy interrogation, the blacksmith spoke about his own suspicions concerning a “stranger” loitering around the bank the day before the heist. With the police certain that it was an inside job, Lyon was arrested and sent to the Walnut Street Prison. Interestingly enough, the stranger Lyon spoke about was arrested soon after. The conspirator, Isaac Davis, was able to gain access to the inside of the bank with the help of his accomplice, Thomas Cunningham, who slept in Carpenter’s Hall the night of the robbery. Within days of their thievery, Cunningham succumbed to yellow fever, leaving all the loot in Davis’s possession. What would have been the perfect heist—a deceased accomplice and another man taking the fall—ended in a comically pea-brained fashion; Davis had the bright idea to deposit the stolen money into the very bank he’d robbed it from. Upon his foreseeable arrest, the harebrained burglar gave a full confession and made a deal to return all the money with the promise of a pardon. Soon after, Davis was once again a free man. Meanwhile, Pat Lyon remained in prison. After he’d spent nearly three months imprisoned in harsh conditions, law officers grudgingly agreed to release him. A grand jury officially cleared Lyon the following year, and in 1805, he won a civil case for false imprisonment and was awarded $12,000. In the end, the Bank of Pennsylvania at Carpenters’ Hall will be remembered as being the first bank robbery in the United States of America.[8]

2 Postwar Japan

On January 26, 1948, a man identifying himself as a health inspector entered the Imperial Bank in Tokyo and deceived 16 people into drinking poison. Within minutes, the unsuspecting victims were writhing on the floor as the callous killer raided the bank, stealing cash and checks. By the end of the heist, 12 had succumbed to the toxic effects.[9] It took six grueling months for police to make an arrest. Their suspect, Sadamichi Hirasawa, matched the description of the murderer, his handwriting was similar to an endorsement on a stolen check, he had a record of unexplained bank deposits, and, ultimately, he confessed. Over the years, however, Hirasawa gained a growing number of supporters who maintained that the United States was behind the brutal plot. Many believed that the culprit was a member of the Japanese army—which was protected by US military authorities. Theories circulated that the robbery was a ploy in order to conduct experiments for the military’s germ warfare unit. The unfounded notion only strengthened following Hirasawa’s recanting of his confession. Despite incessant legal battles for his release, 18 petitions for a new trial were rejected, along with five for a pardon. After 32 years on death row, Hirasawa died of pneumonia in 1987 at the age of 95.

1 Bizarre Phenomenon

“The party has just begun!” exclaimed Jan-Erik Olsson after discharging a submachine gun into the ceiling at Sveriges Kreditbanken in Stockholm, Sweden. It was August 23, 1973, when the brazen robber took four bank employees hostage. The incident would ultimately bring to light a condition that would baffle psychiatric experts for years to come. The demands were straightforward: more than $700,000 in Swedish and foreign currency, a getaway car, and the release of a fellow bank robber and cop killer, Clark Olofsson. Within hours, the demands were met. In the meanttime, the hostages, cramped up in a vault, began forging a bond with Olsson as well as Olofsson, who was permitted inside the bank. By the following day, everyone was on a first-name basis. Perhaps it was the compassion the men showed toward their captives, such as draping a wool coat over a shivering Kristin Enmark, consoling a petrified Birgitta Lundblad, and allowing Elisabeth Oldren to leave the vault when claustrophobia set in. In time, the hostages began fearing the police more than their captors. Five days after the ordeal began, tear gas was pumped into the vault, prompting the surrender of the two perpetrators. Standing in the vault’s doorway prior to the men’s arrest, the four hostages embraced, kissed, and shook hands with Olsson and Olofsson as tears streamed down their faces. Even after the two were imprisoned, their former hostages made jailhouse visits. According to psychiatrists, the four became emotionally indebted to their captors for being spared death. Months later, psychiatrists officially dubbed the bizarre phenomenon Stockholm Syndrome.[10] Adam is just a hubcap trying to hold on in the fast lane.