Even so, recent discoveries showed a surprising adaptability spiced with a few unexpected crafts and building skills. Mesolithic archaeology is also packed with rare artifacts, mysteries, and murder. The most intriguing contribution could be the mysterious key to the history of Stonehenge.

10 Rare Squares

The Cheddar caves in Somerset are an important archaeological site. There, the track record of great discoveries includes the world’s oldest scientifically dated graveyard (10,200 to 10,400 years old). This cache of skeletons was found in 1914 in Aveline’s Hole. When simple engravings were found in Long Hole Cave in 2005, the discovery paled in comparison but only to the untrained eye. The art consisted of three seemingly insignificant squares. In truth, the geometric trio was rare. Only twice before did something similar show up in Britain. The Cheddar panels also resembled others found across Europe, which roughly dated to the same time. Most likely created with stone tools, the squares could be as old as 10,000 years. This means they were created right after the last ice age. Scientists love studying this time due to cultural and environmental shifts. The Cheddar caves were clearly important to Mesolithic communities. The squares could add a little context to this ancient fascination with the place, but first, the meaning of the panels must be deciphered.[1]

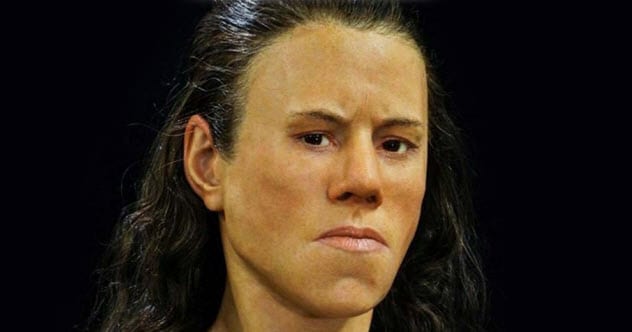

9 Face Of A Teenager

When a community buried one of their own in a cave in Greece, they could never have guessed that people would see 9,000 years later the way she had looked during her lifetime. Nobody knows her story, but the woman was around 18 years old when she died of an unknown cause. Archaeologists found her grave in the 1990s and nicknamed her “Avgi.” Her discovery was not a complete surprise. She rested in a place called Theopetra, an archaeological site with a history of finds from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic periods. In the girl’s cave alone, artifacts covering a slice of 45,000 years have been recovered. Recently, doctors and professionals from many fields have come together to reconstruct Avgi’s face. After carefully sculpting the muscles back onto a replica of her skull, things like skin, hair, and eye color were based on regional genetics.[2] Once completed, researchers got their first good look at a Mesolithic teenager. Avgi had a long face, prominent jaw, and close-set eyes. Her dark looks were also very Mediterranean.

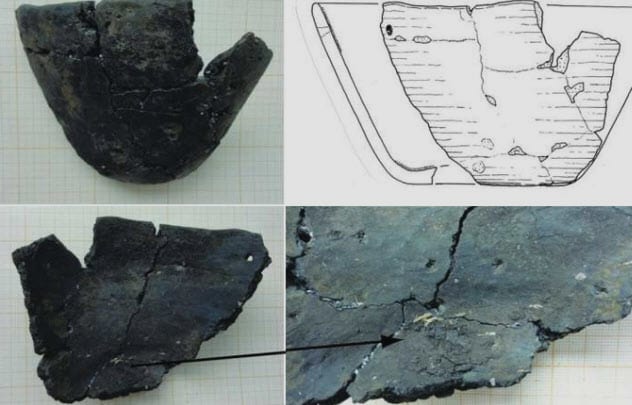

8 They Ate Caviar

A ceramic bowl proved that the Mesolithic menu was not brutish. At least, not in Germany. Contrary to the popular portrayal that people’s culinary skills were restricted to roasting a carcass, a 2018 study found that ancient Germans cooked very well. The vessel was tested for proteins, and the results were something right out of a high-class restaurant—poached caviar. Residue analysis soon revealed what the chef had whipped up that day. The 6,000-year-old meal consisted of fresh carp roe with herbs. Traces of fish stock suggested that the recipe called for the roe to be cooked in this extract (water in which fish was boiled). A crust of some kind was also found. When viewed through an electron microscope, the material was identified as leaves. The type could not be determined with certainty. If not herbs, researchers feel they served a simpler purpose as a kind of cover to keep the food warm.[3] Either way, it shows that Mesolithic cooks were far from primitive. If anything, they prepared meals nearly as well as today.

7 Oldest Thames Carpentry

MI6’s headquarters hug the River Thames in south London. In 2011, they sent an armed response to confront what somebody reported as a group bearing rocket launchers in front of the building. Instead, the security team found excited archaeologists with tripods. While puttering about in the silt, the researchers had discovered the Thames’s most ancient wooden structure. Not only was the age significant, but it also came offering a mystery. The trees were chopped down between 4790–4490 BC when the silt-flooded area was probably dry land. The heavy timbers suggested a permanent residence when people were nomadic hunter-gatherers. They certainly did not make a habit of raising solid structures.[4] Unfortunately, the purpose of the building was lost. The timbers could not reveal the type, either, although it was likely domestic. Researchers suspect that the location was important, perhaps in a religious way, or maybe the area was so rich in natural resources that a permanent home was not a bad move.

6 Snake Stones

In 2016, archaeologists visited Ukraine to excavate an ancient site. Called Kamyana Mohyla I, it was filled with sandstone. Two rocks had strange shapes, which turned out to be artificial. The stones were crafted to resemble snake heads. The older one had a yellow hue and measured 13 centimeters (5 in) by 6.8 centimeters (3 in). Apart from a flattened bottom, the rock was triangular, with eyes and a mouth line. Luckily, it was found near a hearth. Researchers used the fireplace’s organic material to date the figurine to 8300–7500 BC. The younger head also turned up next to a fireplace, which aged it to around 7400 BC.[5] This stony reptile’s head was flat and round with something of a neck and two slits for eyes. This one was also smaller, measuring 8.5 centimeters (3 in) by 5.8 centimeters (2 in). Interestingly, just a short distance away from the site, a fish stone head turned up. Although researchers suspect that the art was ritual, there could be a simpler explanation. Maybe the carvers just wiled away some free time by the fireplace.

5 The Underwater Monolith

A project in 2015 mapped the seafloor around Sicily. To everyone’s surprise, they found what resembled a man-made object at a depth of 40 meters (131 ft) at the Pantelleria Vecchia Bank. Although broken in two, the monolith reached 12 meters (39 ft), was a single stone, and did not match those around it. It also had three large holes, all with similar diameters. One reached all the way through the rock. If this was caused by nature, the process is unknown to science. A better explanation would be that somebody made the artifact, most likely locals from the Mesolithic. One theory suggested that the monolith was a coastal lighthouse with a torch inside the deepest hole. The exact time it was crafted remains as mysterious as its true purpose, but it was probably over 9,500 years ago.[6] Sometime after this date, sea levels rose all over the world. The event drowned an archipelago between Sicily and Tunisia where researchers suspect that the builders originally came from. It remains unknown how a hunter-gatherer society made a monolith that required advanced building skills.

4 A Mesolithic Murder

Around 50 years ago, a skull and burned bone were found in Poland. The 8,000-year-old remains turned up next to a river, together with flint tools that suggested the man was a hunter. After investigating the scorched bone and the badly shattered head, researchers concluded that the twentysomething was the victim of cannibals. In 2018, a new study discovered the real story. It was not much of an improvement. Evidence showed that the man had been murdered. During an altercation, somebody had delivered a devastating blow to his forehead. Despite the horrific impact, he did not die immediately.[7] Scans detected healing around the edges of the fractures. Judging by the progress of the recovery, the man had suffered a drawn-out death that lasted over a week. This solidly ousted the cannibalism theory. The unfortunate man’s remains carry the distinction of being the only healing bones found in Mesolithic Poland. The era included both burials and burnings. A fiery funeral could be why the bone found with the skull showed scorch marks.

3 An Eco Home

A surprising find turned up near Stonehenge in 2015. About 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) away from the famous monument, researchers found what could pass for an eco home (in Mesolithic terms). Around 6,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers found a spot where a massive tree fell over. Showing surprising innovation, they kept the base as a wall and tiled the surface with flint. The hole left by the toppled tree was given a cobbled floor. Some distance away, a wooden pole was staked to support a roof. The latter was probably made of grass or skin. Unexpectedly, the family had a sophisticated way to keep warm. Big stones were heated in a fireplace (located well away from the roof) and placed near the beds to provide warmth. The wooden post dated to 4336–4246 BC, which could change the backstory of Stonehenge.[8] Many feel that the monument’s Neolithic builders arrived from the continent to find an empty landscape. But this home suggested that they encountered a local Mesolithic community.

2 Oldest British Journey

Blick Mead is an ancient camp near Stonehenge. When archaeologists found a 7,000-year-old dog’s tooth at the site, it revealed the country’s earliest journey. Analysis of the canine’s enamel showed that it drank water from the Vale of York region. To reach Blick Mead, the dog and his Mesolithic owner traveled some 402 kilometers (250 mi). As the campsite’s history is vague, the discovery was a big one. Together with other artifacts found earlier, it is now believed that people made a beeline for Blick Mead in ancient times. Not just a few times, either. For some reason, travelers took on grueling distances to reach the camp—a trend that lasted nearly 4,000 years (7900–4000 BC). This unusual attraction to a location is a first for Europe. The popularity could have meant that the site was a meeting place to share information, trade, and find marriage partners. Researchers believe that Blick Mead is a piece of Stonehenge’s puzzling origins, although the two do not yet fit together.[9]

1 Remarkable Climate Survivors

When the last ice age ended, the climate was volatile. The first people to move back into Britain were a Mesolithic group who left behind Star Carr, a priceless archaeological site. Found in the 1940s, the location produced Britain’s oldest house and some of the most ancient carpentry ever discovered. A 2018 study revealed that the mysterious villagers were more amazing than already believed. Past arguments insisted that the dramatic climate shifts that happened around 11,000 years ago acted like a human cull in Northern Britain. The pioneers at Star Carr soundly thrashed that theory. Their community suffered two killer episodes of cold weather around 9,300 and 11,100 years ago. It was not just a chilly season, either. Instead, temperatures plummeted abruptly and stayed low for as long as 100 years at a time. Researchers expected severe repercussions at Star Carr. Instead, evidence showed that the people slowed down slightly during the first winter. After that, they aced it. They successfully exploited their environment for food, constructed timber structures, and kept their society stable during very dangerous times.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages