Although potential dangers related to personal privacy have caused controversy about the use of these technologies, it seems clear that these ten cutting-edge innovations in the future of forensic science also promise enormous benefits to authorities, victims, victims’ families, and society in general.

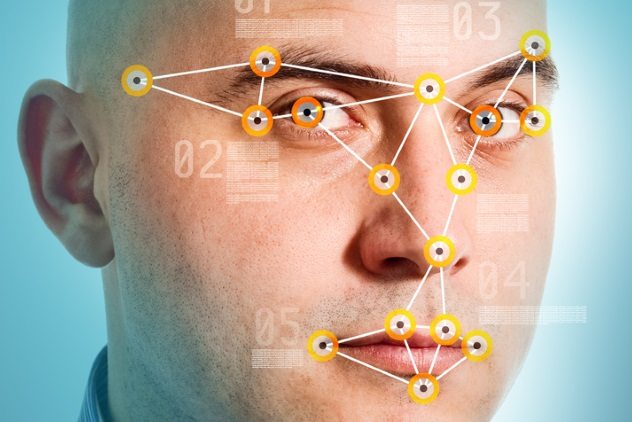

10 Facial Recognition Algorithm

Smartphones and other mobile devices equipped with facial recognition software can already identify individuals under ideal conditions, such as having a good-quality photo of the person in a database with which to compare in real time, but such conditions often don’t exist. In addition, people’s faces change over time, and donning a pair of sunglasses or growing a beard can prevent the technology from making a match between the photos. Videos, which offer a series of images, should, in theory, provide a better chance for forensic science to identify a suspect, but that doesn’t always happen, as the case of the Boston Marathon bombing proves: In a test of three facial recognition systems, only one identified Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, and none of them recognized Tamerlan Tsarnaev, who wore sunglasses. Animetrics may have the answer to these problems. The company has developed software that converts 2-D images into “simulated 3-D models of a person’s face” in about a second, and the software’s users can alter a suspect’s attitude or position. The resulting “headshot image” can be analyzed by all facial recognition algorithms. On a sophisticated laptop, the headshot can be matched against as many as one million faces. For smartphones, the algorithms must be scaled down, which makes them less effective. Experts are confident that the limitations of smartphones can be offset in the future by using the cloud to compute the algorithms. Then, the technology will fit into the palm of a police officer’s hand, allowing almost instantaneous identification of suspects.[1]

9 Fingerprint Analysis

Although computers expedite database searches for fingerprints on file that may match one obtained at a crime scene, an analyst makes the final judgement as to whether the print that’s on hand is of adequate quality to proclaim a match. If a matching print isn’t in the database, no match can be made, no matter the quality of the fingerprint from the crime scene. But, even if no match is made, or two analysts differ in their opinions that a match has occurred, the fingerprint may still have evidentiary value. Annemieke van Dam of the University of Amsterdam’s Academic Medical Center points out that fingerprints consist, in part, of “proteins and fats secreted from our skin,” which “could reveal a host of information about the person who left them,” including his or her diet. In the future, van Dam predicts, fingerprints may even identify whether the person who left them is a meat-eater or a vegetarian. Other researchers have found that fingerprints can also show whether the person who left them behind handled a condom and, if so, its brand. Van Dam is confident that, in the future, such fingerprint analysis results will be commonplace. That’s not all. In the future, fingerprints’ DNA could be used to develop a suspect’s “genetic profile,” allowing investigators to acquire a good idea of the subject’s physical appearance.[2]

8 Hair And Eye Color Prediction

A forensic procedure known as pheontyping allows investigators to predict a suspect’s hair and eye color, which means police need not depend on whether the person’s DNA profile is already stored in a database. Using 24 DNA variants that predict eye and hair color and six genetic markers, the HIrisPlex system can predict blonde hair 69.5 percent of the time, brown hair 78.5 percent of the time, red hair 80 percent of the time, and black hair 87.5 percent of the time. The system can also differentiate between brown-eyed, black-haired people of European and non-European origin in 86 percent of cases. Tests indicate that geographic ancestry doesn’t affect results. Although this tool isn’t widely used as yet, it’s likely to become an important instrument of forensic investigation in the near future.[3]

7 Microbiomic Identification

Plenty of microscopic organisms live in and on our skin and hair. In the future, these communities of microorganisms, known as microbiomes, may help police catch criminals. Although microbiomes outnumber our own cells 20 to one, no two people’s microbiomes are identical, and the communities remain stable over time, except after sex. Although pubic hair recovered from sexual assault suspects may not contain the roots in which the suspect’s own DNA resides, the microbiomes in the hair may help to convict him. This microbial DNA differs in males and females, since different microbial communities live on and in the pubic hair of men and women. Since these communities are unique to each individual, they identify whether a particular suspect committed an assault. Following sex, the microbiomes in both the male and the female appear to transfer from one party to the other, making the normally stable communities of microorganisms more like one another, indicating that a sexual act occurred between a particular man and woman. Although this cutting-edge technology isn’t ready for use in the courtroom yet, because it must first be shown “to have low false positive and false negative rates,” scientists predict its use in convicting perpetrators of sexual assault will soon become routine, supplying investigators and prosecutors with an effective new tool against sexual assault.[4]

6 Tattoo Matching

The use of a database containing poor-quality images of tattoos photographed by security cameras, suspects wearing disguises, and overreliance on key words to conduct database searches have hampered investigations of crimes. TattooID, a new computer program, has improved this situation. The software is efficient because it identifies key points (“essential common points”) between the database image of a tattoo and the surveillance videotape image or police photo of a suspect’s tattoo, the same way other programs compare fingerprint images to determine matches. The program could also identify specific gang members, who often wear a common tattoo.[5]

5 Morphometrics

In the future, morphometrics (the measurement of body shapes) may be used to identify the skeletal remains of missing children, something which is extremely challenging for current forensic experts. The breakthrough came with scientists’ recent understanding that, “Children’s faces attain the shapes they will have in adulthood much earlier than previously thought,” according to Associate Professor Dr. Ann Ross of North Carolina State University’s anthropology department. Skull shape allows anthropologists to distinguish various geographical population groups. Now, these scientists will be able to apply this procedure to younger individuals than ever before. In one case, Ross was able to determine the Mesoamerican origin of a ten-year-old boy’s remains, making his facial reconstruction possible. Before this breakthrough, it was thought that only the skeletal remains of people 18 or older could be identified.[6]

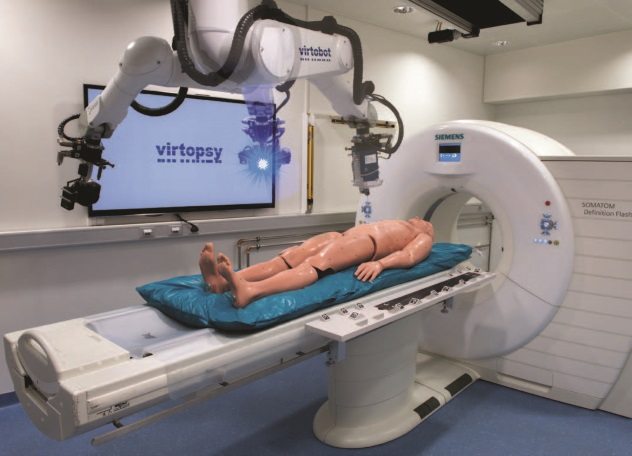

4 Virtual Autopsy

For religious, personal, or other reasons, spouses or families sometimes do not want their murdered loved one’s remains to be autopsied, even when the procedure could provide information valuable to the apprehension of the deceased relative’s killer. Although, in such cases, courts often overrule the spouse’s or family’s decision not to permit the autopsy, such orders intensify relatives’ anguish. In the future, it may no longer be necessary to conduct physical autopsies, now that virtual autopsies have become possible. Virtual autopsies are noninvasive, damaging neither the body nor forensic evidence. Instead, 3-D models are used, and computer acquisition of data allows an immediate second opinion, should it be needed. The procedure is not widely used at present because it is fairly expensive, but the cost is expected to decrease as virtual autopsies are more frequently conducted in the future. Virtual autopsies have the added benefit of being always available once they have been performed. In cases involving bite marks, 3-D images from the virtual autopsy can be compared to a suspect’s own dental records, if such records exist, and can help prosecutors to better understand victims’ injuries. Dr. Michael J. Thali, professor and chair of the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Zurich, said that virtual autopsies will make imaging “the gold standard in the future examination of forensic evidence.”[7]

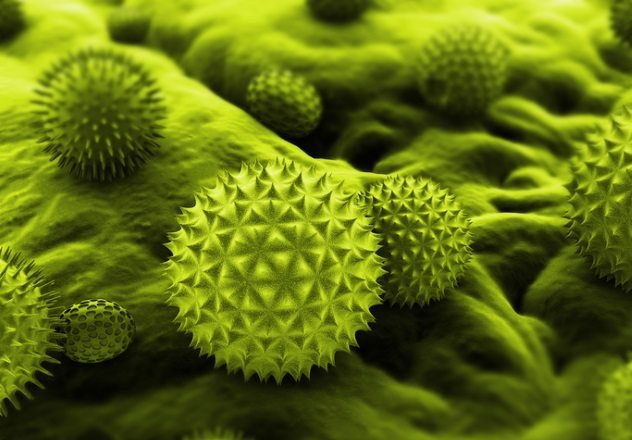

3 Pollen Biomarkers

Palynology, the study of pollen, has become one of the latest disciplines added to the growing field of forensic science. Pollen is everywhere flowering plants exist, including deserts and caves, and flowers blossom at various times. These two factors establish a specific “signature” for pollen grains, making them biomarkers linked to specific times and places. A new pollen identification technique will lead to the use of palynology to solve crimes that otherwise might have gone unsolved. Although pollen has already been used to determine where death originally occurred for bodies found in common graves in Bosnia and to link a robber to his crime in New Zealand, it hasn’t yet been widely employed in solving crimes, nor have all of its applications been applied. It may be useful in missing persons cases and in charting a criminal’s travel history. The procedure is limited by the fact that there aren’t many palynologists (only one works full-time in the US) and that the sheer number of flower species (400,000) throughout the world makes identification difficult. The use of DNA barcoding and sequencing, although expensive, can increase the accuracy of identifying a particular type of pollen, and it’s likely that pollen biomarkers will become widely used in the future of forensic science.[8]

2 Vehicle Systems Forensics

Two parts of motor vehicles, the infotainment system and the telematic system, are potential sites for forensic evidence. The former system allows drivers or passengers to connect their smartphones using Bluetooth technology or to play music. The latter system isn’t visible. A “small box,” it houses technology which interacts with websites such Facebook or Pandora. Once drivers or passengers use their smartphones in a vehicle, their cars or trucks retain data from the devices even after they’ve been disconnected from their infotainment systems, since phone calls, contacts, and SMS messages are all synced to their vehicles. If connecting using a cable file system, file names, time stamps, and various other metadata are also collected and saved to some extent, usually even if users deny the system access to such data. Thanks to nearly 70 interconnected electronic control units (ECUs) scattered throughout vehicles, such data as where and when a car door is open as well as information about airbags, seat belts, and taillights are collected and stored, making vehicles susceptible to remote control. ECUs also control acceleration and braking. Now and in the future, all this information can provide valuable forensic evidence against perpetrators of crimes, indicating the places their vehicles traveled, senders’ and recipients’ telephone calls and text messages, websites accessed, times and places at which doors were opened, and times when vehicles accelerated or slowed. In hot pursuits, suspects’ vehicles could even be remotely controlled by pursuing police officers.[9]

1 Portable Police Labs

According to forensic scientist Peter Massey, “The goal [of forensic science research] is to bring the laboratory out to the crime scene.” Portable forensic labs will negate the need for sending specimens and data to distant facilities. Test results will be immediate, rather than delayed. A number of new techniques will help to facilitate this new wave of field forensics. For example, Raman spectroscopy allows investigators in the field to determine whether a suspicious powder is explosive, eliminating the need to use bleach to destroy such substances—along with potential evidence. For years, forensic laboratories had to use big, heavy equipment to identify drugs through the use of various gases, liquids, and solids, but now, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy can accomplish the same task in less time, without the need for such materials. “Handheld electronic sniffers” may replace canine units dedicated to the detection of drugs, and “flashlight detectors” may replace breathalyzers and field sobriety tests for alcohol-impaired driving. Near-infrared light scanners image human veins, which can also help police to identify a potential suspect during an investigation. Portable forensics labs could also be equipped with devices capable of transmitting data obtained through the use of facial recognition software and fingerprint scans to government databases for comparison with stored files of such information. These technologies are already used by the FBI and in several states, Massey said, but, in the future, their employment should become more widespread. The University of New Haven’s Marvin K. Peterson Library hosted Massey’s lecture, and its librarian, Hanko Dobi, agreed with Massey: “It’s great how the crime scene is now becoming the real laboratory.”[10]