10Sitting atop a pillar . . . for years

In the late Roman Empire, Christianity became the official state religion. Despite the turnaround from being forbidden and often punished by death to becoming the only tolerated religion, many Christians felt uneasy with the Empire. Rome spent centuries as the epitome of evil in Christian tales, and suspicions about the Empire did not disappear overnight. Many Christians felt that Roman society was still overly sinful. In response to these social changes, many Christians took up ascetic practices to separate themselves from wider society. One of the most extreme practices to come out of this period was that of “pillar sitting.”[1] Essentially, a Christian would choose to spend much (if not most) of his life atop a raised platform—separating himself from the world. His survival would be at the mercy of the elements, and the charity of the community. According to tradition, the first such pillar sitter was a man named Simeon Stylites the Elder. He took up this practice in the Syrian city of Aleppo in the early fifth century. Afterward, others who followed in his footsteps were called “Stylites” (after the Greek word for pillar, “stylos”). The practice was quite popular and well-known for several centuries in the Eastern portion of the Roman Empire, and the later Byzantine Empire. However, it never caught on in Western Europe, with only one such account of a Stylite performance taking place in France.

9Dwelling in Caves . . . On the Side of a Sheer Cliff

In ancient times, the region that is present-day Afghanistan was a thriving center for Buddhism. The village of Bamyan in central Afghanistan was known for having been the site of giant Buddhist rock-cut carvings that stood for centuries. While these massive carvings were unfortunately destroyed by the Taliban in 2001, the region is still home to other Buddhist architecture. Namely, Bamyan is home to hundreds of caves that ancient Buddhists carved into the surrounding cliffside and used as dwellings. These rock-cut caves in the hills behind the village offered monks quiet, isolated spaces where they could engage in meditation without being disturbed by worldly affairs.[2] Much like the Stylites, these monks also lived off the charity of the village and religious pilgrims, often spending extended periods in the caves. What gives this practice that extra layer of challenge is that many of these caves were elevated hundreds of feet from the ground. Reaching them was no easy task, and leaving was just as perilous. Even the present-day inhabitants of these caves point out the difficulties of reaching the higher ones.

8Isolating Oneself in a Room . . . For Life

During the Middle-Ages, thousands of Christian men and women entered into monastic orders. While the orders varied in their practices, one of the more notable ones for this list is that of the anchorite or anchoress. While some monks and nuns lived in small, isolated communities, these men and women walled themselves up inside small rooms where they would spend the rest of their lives.[3] Fortunately, these cells were usually built with a tiny window to the outside world. This window let people from their community deliver food and check up on them. Often, these cells were built adjacent to the local church so that the hermit would have some contact with the locals. Ironically, the men and women living these extreme lives often acquired reputations and became popular. A good example is Julian of Norwich, a 14th-century anchoress in England. Locals and pilgrims alike flocked to her cell to seek her spiritual counsel and guidance.

7Walking over Burning Coals . . . While Carrying a Burning Hot Pot

Firewalking over hot coals is a practice found across the globe. Numerous cultures employ firewalking in one form or another, often as a rite of passage. However, among Hindus of certain parts of South India, firewalking is often part of an elaborate ritual vow. Devotees ask for something from a deity and promise to do something in return. In this case, that something in return is walking across burning coals while carrying burning pots. The most well-known of the firewalking rituals occur at the temples to the Goddess Mariamman in South India.[4] Before the ritual begins, pilgrims bring pots of clay or other fire resistant substances. The pots are filled with hot coals, kindling, or burning oil. The devotees then carry the pots in their hands or on their heads across the burning coals. In some cases, the practitioner also has to carry the pot throughout their village before they even reach the coals at the end of their run. Depending on the number of firewalkers, the ritual can go on for hours. One source reported that sometimes the heat from the ceremony reaches such extreme temperatures that the walls of the nearby temple need to be continually doused in water to cool down. One can only imagine the rigors for the people taking part.

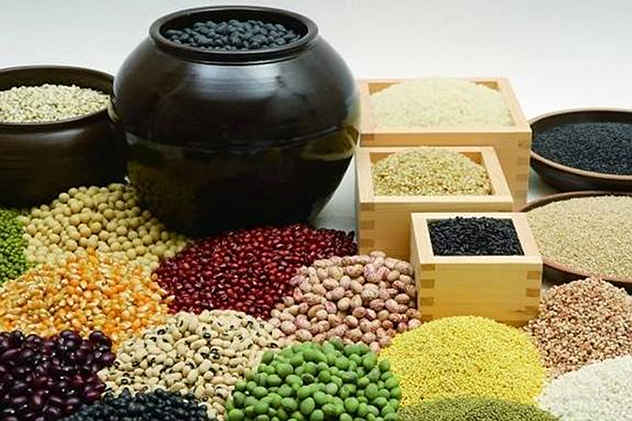

6Avoiding Staple Foods . . . Until You Stop Eating All Together

According to Daoist philosophy, it is possible for humans to obtain immortality. While many texts and their interpreters disagree on the means and the ultimate form of immortality, they do agree that a person can achieve immortality through transforming their body. This process of bodily transformation is often translated as “inner alchemy” and involves various rigorous disciplines and practices. One of the most well-known practices associated with inner alchemy is bigu, or “grain avoidance.” Grain avoidance usually refers to the five grains of traditional Chinese agriculture. However, grain avoidance was also interpreted to apply to any staple food.[5] The rationale behind this form of fasting had to do with Daoist understandings of the body. It was believed that food, rather than extending life, reduced it. Ideally, a specialist would learn to live without food, and thus live forever. The practice would take part in lengthy stages. In the first stages, the specialist would slowly cut all grains from their diet. Following this, the more extreme devotees would keep cutting different foods until they stopped eating altogether.

5Circling the Temple . . . While Rolling across the Ground

A common Hindu devotional practice is to circle a temple or religious icon in a clock-wise manner. Having your right side always facing the center of the temple is considered a sign of respect. In some cases, it is not uncommon for pilgrims to circumambulate a temple numerous times under the scorching daytime sun to prove their devotion.[6] A more extreme version of this practice also occurs at the temples of Mariamman in South India. There, rather than walk the circumference of the temple, pilgrims will vow to do so by rolling on the ground. This includes rolling through crowds, over dirt and debris, and any other obstacle that might come up. Both men and women perform this practice, with men often stripping down to a single garment covering their waist. As an added level of rigor, certain devotees circle the temple up to one-hundred-and-eight times in a single session.

4Sacrificial Initiation Rituals . . . Where You Play the Sacrifice

The ancient Iranian god Mithra held an unusually widespread following. Not only was the deity worshipped before and during the Zoroastrian period of ancient Iran, but he was also exported to the Roman Empire. Roman soldiers stationed on the front, or campaigning against the Persian Empire, were likely the first European devotees. Sanctuaries dedicated to the god have since been found across Europe. Roman rituals surrounding Mithra were different than their Persian counterparts. They reflected the rough lives of the soldiers who joined these male-exclusive cults and were suitably challenging. Namely, entering the cult and moving up into its higher grades of membership required devotees to pass a series of initiation rites. While some of these rites seem similar to the hazing at modern fraternities, others were much more psychologically intense.[7] One of these ceremonies involved a ritual meal. This may have included eating the flesh of a ritually slaughtered bull, but it also required acting where one of the members played the part of the bull. The member would be blindfolded and paraded around the hall before being ceremonially “slaughtered.” It is not clear from ancient sources whether the men playing the bulls knew their part would involve a symbolic death, or if it was a surprise with their lives being spared at the last minute.

3Living as a Vegetarian . . . Without Being Able to Prepare or Harvest Your Own Food

From the third century to the fifteenth, Manichaeism was one of the world’s major religions. However, the religion has since gone extinct. Today, it only exists in textbooks and artifacts. Fortunately, scholars have been able to assemble a fairly complete picture of the religion and its practices. Similar to Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, Manichaeism was divided between everyday laypeople and a clergy who lived monastic lifestyles. Like Christian monastics, these men and women took vows of poverty, service, and celibacy. However, while Christian monastics would consume wine during Mass, and even enjoy beer and cheese on occasion, Manichaeans had no such luxury.[8] Apart from being strict vegetarians, Manichaean monks were forbidden from working the land or performing any activity which would provide for themselves. As such, they required the constant support of laypeople to survive. Curiously, laypeople had a motivation to feed their clergy other than the good deed of keeping them alive. Manichaeans believed feeding these men and women helped remove sins from the community. They also believed that all things in nature had living souls inside them. When the clergy ate the food they were given, they were effectively liberating the souls inside that meal.

2Celebrating the Urs Festival in Ajmer . . . By Shoving a Knife in Your Eye

Urs is a six-day festival celebrated by Sufis in a number of cities, the most famous taking place in Ajmer. The festival commemorates the death anniversary of Moinuddin Chishti, a Sufi saint and founder of an order that bears his name. Though the saint is a local figure, pilgrims from all over the world flock to the festival to take part in the celebrations and witness the challenges that many devotees put themselves through. Over the course of the six days, devout men will perform a series of grueling acts. These include walking seventy-five miles to a visit a shrine, piercing their skin with hooks, and gouging their eyes with swords and skewers. These shocking acts are not meant to be masochistic. On the contrary, they are selfless demonstrations of their faith and commitment to their order.[9] For the curious, it should be noted that these acts of self-torture are not something the faint of heart will want to witness.

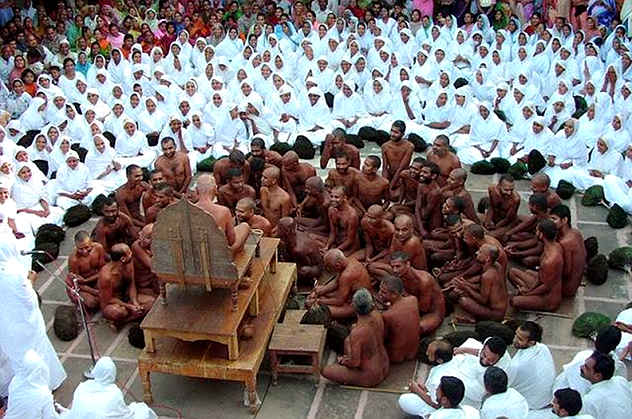

1Living under the Open Sky . . . Without Ever Wearing Clothes

Jainism is an ancient religion still practiced today in parts of India and among ex-pats across the globe. While most Jains follow certain codes of conduct, such as vegetarianism and pacifism, the monks of their communities maintain even more rigorous lifestyles. Jain monastics are divided into two orders, the Svetambara and the Digambara. Both follow similar codes and expectations, such as abstaining from violence, lying, marriage, certain foods, and any “harmful” activities (such as killing so much as an insect). The main difference is how these codes are interpreted and put into practice. While the Svetambara consistently travel and beg for charity, the Digambara push themselves to the extreme limit of human survival.[10] Digambara monks are easily recognizable from their Svetambara peers due to their utter lack of clothing. These male-exclusive monastics vow to never wear garments (save for perhaps a beaded necklace) and live fully exposed to the elements. They live outside the entire year, migrating by foot from region to region to escape seasonal weather changes that would make their lives impossible. When it comes to begging, they are not even permitted to carry bowls but must eat instead from their cupped hands. Alicia Sarkar is a Bengali-Canadian writer and researcher. She spends her time diving into the weird and forgotten parts of history.