10 Sirens And Sea Monsters

Taxidermies of sirens, mermaids, and other sea monsters were a common sight in cabinets of curiosities, and they were usually produced by assembling different parts of fish. In Ambroise Pare’s (1510–1590) Of Monsters and Marvels, the author claims that just as there are many monstrous creatures on Earth, it must not be doubted that there are equally monstrous creatures living in the sea. Sirens, mermaids, and tritons are described as being not only partly fish and partly human but also strange hybrids of fish, monkeys, and bears! Perhaps the most original among them, the monk-fish and the bishop-fish are featured in some of the most popular bestiaries of the time (those by Ambroise Pare, Conrad Gessner, and Pierre Belon). Scholar Guillaume Rondelet (1507–1566) claimed to have seen a portrait of a bishop-fish: [From] Gisbert, a German doctor to whom it was sent in Amsterdam with a text assuring him that this sea monster in a bishop’s garb had been seen in Poland in 1531 and taken to the king of said country, making certain signs to show that it much desired to return to the sea, where once brought back it threw itself in immediately.[1] Although Rondelet reported the story, he did not believe that the fish had made the sign of the cross before swimming back into the water.

9 Automata

Automata, the first robots, were real mechanical marvels, and they were much sought-after for display in cabinets of wonders. Milanese collector Manfredo Settala (1600–1680), for example, owned the automaton of a devil. He placed it at the entrance of his cabinet, where the mechanism would stick out its tongue and make loud sounds when someone entered. These masterpieces of ingenuity became very popular in the 17th and 18th centuries when the philosophical understanding of nature as a machinery encouraged artisans to try to imitate living beings artificially. Jacques de Vaucanson (1709–1782) invented a mechanical duck which could apparently digest food. (The automaton was then proved to be a hoax as already-digested food had been inserted in the machine.) Meanwhile, Swiss watchmaker Pierre Jaquet-Droz (1721-1790) built automata capable of playing musical instruments and writing.[2] In 1780, Abbot Mical built a series of mechanical talking heads in an attempt to artificially recreate human speech. The heads could utter sentences like “The king brings peace to Europe” and “Peace crowns the king with glory.” With this creation, the ecclesiastic hoped to win an annual competition at the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg.

8 Paradise Birds Without Feet

Paradise birds greatly excited the European imagination when they first reached the West through trade routes with the East. According to popular legends, these colorful creatures had no legs. Supposedly, they lived in perpetual flight, sustained by their abundant plumage, and fed off dew or air. Even Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), who established the classification system still in use today to name and rank organisms, called the bird Paradisaea apoda (“bird of paradise without feet”). When traders began to import birds of paradise in the West, their legs were amputated to make money off the myth.[3]

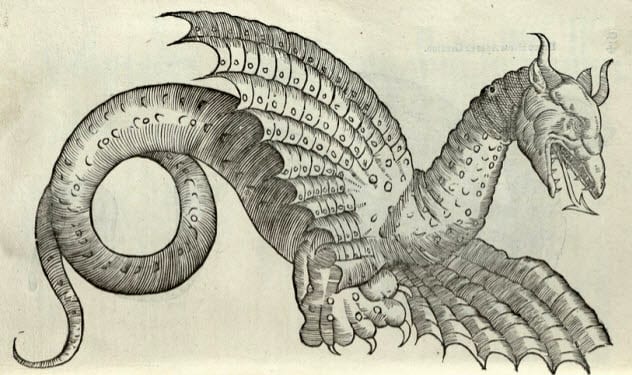

7 Aldrovandi’s Dragon

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) is one of the most famous collectors in history. Professor of natural philosophy at the University of Bologna, he assembled an immense collection of natural specimens and founded one of the first botanical gardens. Aldrovandi wrote numerous treatises of natural philosophy, including A History of Monsters and A History of Serpents and Dragons. In the latter, he detailed the discovery of a dead dragon found in the fields surrounding Bologna. The creature was a “long-necked, long-tailed, scale-covered biped with a thickened torso and a forked tongue.” Aldrovandi was particularly proud of being able to add the creature to his collection. Its oddity made it a rarity. In Aldrovandi’s words, “Serpents naturally do not have feet.”[4] Belief in the existence of dragons was not unusual in Aldrovandi’s time. In one of the most famous books of the time, Conrad Gessner’s Historiae Animalium, the author claimed that he “heard that on the edge of Germany near Styria, many flying four-legged serpents resembling lizards appeared, winged, with an incurable bite.”

6 Unicorn Horns

Unicorn horns, proudly displayed in cabinets, were most likely narwhal horns. These objects were believed to be powerful antidotes against plague, bites from serpents, and rabid dogs. It is even said that Mary Stuart (1542–1587), Queen of Scotland, would use a piece of unicorn horn to prevent her food from being poisoned. Conrad Gessner (1516–1565), the author of one of the most famous bestiaries ever made, dedicated a page to the unicorn in his Historiae Animalium.[5] Most unusually for the contemporary reader, the image and description of this fantastical being is found side by side with an entry about the common mouse. Using biblical, medieval, and mythological sources, Gessner claimed that the unicorn had wondrous properties, including curing epilepsy and purifying water. It was generally believed that unicorns would have let themselves be approached only by virgin women. Upon seeing a virgin, the animal would have rested its head in her lap. Due to this association between a virgin lady and her womb, the unicorn came to symbolize Christ in the Middle Ages.

5 Anatomical Tableaux

Misshapen or “monstrous” creatures had been present in cabinets of curiosities since their appearance. Their oddness testified to the variety of the natural world, and their rarity increased the value of the collection. Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731), the owner of a vast collection of curiosities, combined scientific exploration with entertainment and wonder in his own work. A botanist by profession, he created a method to preserve specimens that he sold to Peter the Great, the Russian monarch. This method allowed Ruysch to inject different colors into the veins of the specimens, highlighting the paths taken by blood in arteries and veins. Ruysch is famous for his dioramas,[6] which were very popular in 18th-century cabinets. In these tableaux, he created small scenes where human fetal skeletons were arranged in dramatic positions in a reconstructed natural environment. However, the natural environment was actually composed of body parts: gallstones and kidney stones for rocks, veins and arteries for trees, and lung tissue for bushes and grass. These tableaux had an allegorical theme, and they often constituted a reflection on the transitory nature of existence.

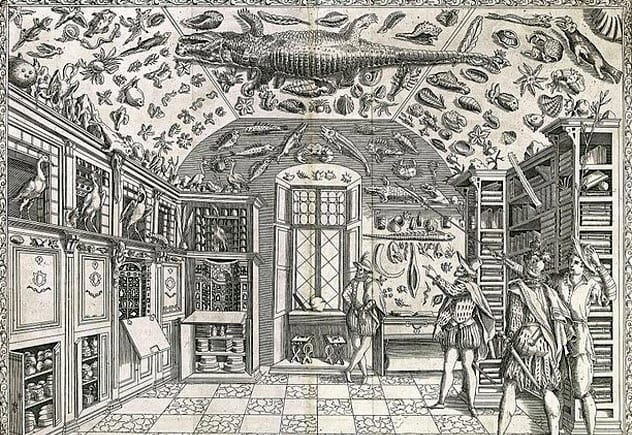

4 The Stuffed Crocodile

The stuffed crocodile was one of the most common objects in cabinets of curiosities. It was featured on the covers of two of the most famous catalogs of collections (namely the ones of Ferrante Imperato and Ole Worm). The crocodiles’ frequent appearance in cabinets is probably because they were exotic and monstrous and their amphibian existence raised questions about the natural world. In his Of Monsters and Marvels, Ambroise Pare described the paradox of the half-fish, half-terrestrial crocodile: It has such an impedite [rudimentary] tongue that it seems not to have one at all, which is the reason why it lives partly on land, partly in the water; as, being terrestrial, it takes the place of a tongue for him, and as, being aquatic, he is without a tongue. For fish, either they have no tongue at all, or they have one that is very tied and impedite.[7] Of course, always according to Pare, the crocodile also had medicinal properties. Out of it, a medicine could be made which cured blemishes on the face. Its gall was good for cataracts, and the blood could make one’s vision sharper.

3 Bestiaries

Renaissance bestiaries (early encyclopedias of animals) included common, exotic, and fantastic creatures, often drawn after narrations from the travelers to the New World. Next to a picture of the animal, the author would describe the creature, its habits, and its usefulness to humans, as many animals were thought to have medicinal properties. Although it is not always clear how much the authors believed in the existence of such animals, the fact that they were depicted and included in bestiaries lent credibility to their existence. The long tradition of bestiaries, which were already common in medieval times, is tied to the one of cabinets of curiosities. One reason was their classificatory purpose. Also, cabinet owners soon began to create their own catalogs and natural histories, small encyclopedias explaining the characteristics of the objects contained in their collections. Dutch zoologist and collector Albertus Seba is an excellent example. He commissioned beautifully accurate illustrations[8] of his specimens and published them in color in a four-volume catalog.

2 Herbaria And Mandrakes

Like bestiaries, herbaria were catalogs where natural specimens were listed and described, often with particular attention to their medicinal properties. And just like bestiaries, the limit between science, imagination, and wonder was very elusive. Perhaps the most curious among the plants often contained in such works is the mandrake, or Mandragora. Due to their resemblance to the human form, mandrakes were often depicted in the shape of little men or women in Renaissance herbaria. It was thought that, in being removed from the ground, mandrakes would scream loudly and the noise would be deathly to those who heard it. Numerous illustrations show mandrakes being removed from the ground by tying their heads to dogs while the owners wait safely in the distance. Naturalist William Turner (1509–1568), the author of the Niewe Herball, described the medicinal properties of mandrakes as follows: Of the apples of mandrake, if a man smell of them thei will make hym slepe and also if they be eaten. But they that smell to muche of the apples become dum . . . thys herbe diverse wayes taken is very jepardus for a man and may kill hym if he eat it or drynk it out of measure and have no remedy from it. [ . . . ] If Mandragora be taken out of measure, by and by slepe ensueth and a great lousing of the streyngthe with a forgetfulness.[9]

1 Decorated Nautilus Shells

These unusual nautilus shells were frequently found in cabinets of curiosities. Sometimes, the shell itself was painted, as in the specimens contained in Albertus Seba’s catalog. In other cases, the object was mounted on a richly decorated pedestal. Sometimes, these objects had a practical purpose, and they could even be used as cups.[10] The fact that nautilus shells were artificially decorated embodied a common belief behind the assembling of cabinets of curiosities—that nature could be improved through human intervention. Like the whole cabinet, the decorated shells described the interaction between the world of artifice and the world of nature and the wonders that both produce.