These artifacts open unseen glimpses into expeditions and little-known military traditions. Even more enticing, they allow the living to meet incredible prehistoric guests. Newly revealed images can also show doomed men, the start of movements, or moments too graphic to have been displayed in the past. Of course, newly presented artifacts aren’t without their controversies. Just to make things interesting, some of the most precious finds are also the most disputed, with background stories that don’t always add up.

10 Nightingale’s Amulets

Florence Nightingale became famous for caring for the Crimean War wounded and opening the first nursing school in 1860. Five years before she traveled to Istanbul to nurse soldiers, Nightingale visited Egypt. The 1849 trip was purely recreational.[1] The letters she wrote to her sister provide a look at Nightingale outside of her usual historical arena. They reveal an adventurous woman who ended up rather disappointed. She had gone to Egypt hoping to find treasure. The dazzle quickly faded when all she was given were a few amulets. She sent them to her sibling, Parthenope, along with letters in which Nightingale described some of the items as “rubbish.” Not every trinket was a waste of her time. The Lady of the Lamp bought four official seals, one of which had belonged to Pharaoh Rameses the Great who was Nightingale’s hero. She told her sister to give away the rubbish if she wanted. However, the items remained with the family, who recently donated everything to the World Museum in Liverpool for an exhibition. The collection included the unfavored artifacts and her precious seals, which Nightingale mercifully never realized were forgeries.

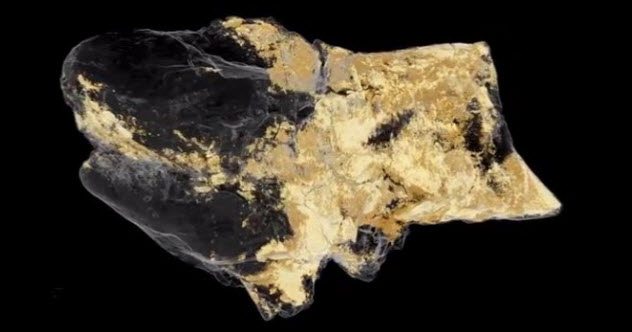

9 A Dinosaur Brain

In 2016, scientists made it public that a dinosaur’s brain had been found. Although it’s not the usual sort of stuff found by fossil hunters, one bone seeker picked up an odd pebble in Sussex in 2004. It turned out to be the fossilized gray matter of a 133-million-year-old dinosaur. Not only was it the first confirmed dinosaur brain tissue but it also came from a particularly large herbivore that was over 12 meters (40 ft) long. Researchers believe that the organ shrank after death but was still remarkably small in life. In fact, during the Iguanodon-like animal’s life, it filled only half the entire brain case.[2] Under the microscope, the remarkable find showed things that scientists have never seen before—dino meninges (the tissue film that envelopes the brain), collagen, blood vessels, and possibly neural tissue from the cortex that contained capillaries. The structure was similar to that of crocodile and bird brains, which strengthened their theoretical evolutionary bond with dinosaurs. The brain, likely pickled in a swamp or bog, allowed an unprecedented look at dinosaur brain biology, intelligence, and behavior.

8 Khroma

Thousands of years ago, a baby mammoth died from anthrax. Its body remained preserved in Siberian ice until 2009 when it was discovered in the Yakutia region. Named Khroma, it was loaned to France the following year to be exhibited for the first time. The mummified mammoth, with its fur intact, went through its own kind of quarantine. A living jet-setting animal would just have to wait at a quarantine facility, but Khroma was taken to Grenoble as soon as it landed in France. There, at a special facility, the woolly calf was thoroughly zapped with gamma rays. Russian news reports claimed that anthrax had killed it. The treatment made sure that the lethal bacteria would not be part of the exhibition.[3] Cleared of any crowd-decimating pathogens, Khroma went on display at the Musee Crozatier. The 1.6-meter-long (5 ft) calf could be viewed in its own chilly cryogenic chamber. The Ice Age kid may not be the first mammoth found in Siberia, but it is likely the most ancient. Tests suggested that it could be 32,000–50,000 years old.

7 The Military Art Of Quilting

The last thing one might connect to warfare is a group of soldiers absorbed in their own quilting projects. Yet, male needlework is a tradition that spans centuries, wars, and continents. In 2017, pieces created by soldiers were shown in the US for the first time. The 29 quilts included creations from England, the United States, and Austria. Others were made during Prussian conflicts, the Napoleonic Wars, and British wars in India and South Africa. What is so remarkable is that the creators were men, not traditionally taught to sew, who forged masterpieces from any rag they could get. Pieces of uniforms, fabric leftovers, and even blankets were blended with dexterity and flair. One of the most complex is an interwoven wonder of 25,000 pieces. Another is a magnificent altar cloth that was made by 138 men.[4] Although common back in the day, fewer than 100 quilts survive and each is unique. At first, they were mistakenly thought to be the product of bored soldiers recovering in hospitals. Subsequent research proved that the quilts came from bored soldiers everywhere, including in the trenches and prisoner-of-war camps. Quilts were also made by those who wanted to commemorate friends lost in battle.

6 The Infanticide Painting

Infanticide (the act of killing a baby) was captured on canvas by artist Joseph Highmore. Painted 300 years ago, the stark image shows a woman strangling a struggling infant as an angel tries to stop her. Highmore was known for his sympathy toward vulnerable and exploited women. During the 1700s in London, children born from rape or mothers abandoned by their partners were a social disgrace from which no woman could bounce back. Such pregnancies were often hidden and the newborns killed. The painting shows one such desperate girl, stopped in time by the angel of mercy who points toward a building. This structure, the Foundling Hospital, still exists. Newly created by the time Highmore (who was also a benefactor) painted it, the hospital was opened by a sea captain after he found a murdered infant in a gutter.[5] The orphanage offered women the chance to abandon infants safely, and some left tokens to later reclaim their children. The Angel of Mercy was deemed too graphic to display, even by the hospital. But in 2017, the institution finally showed the painting in its museum, on one of the walls for which Highmore intended it centuries ago.

5 Little Foot

Paleoanthropologist Ron Clarke was working in the Sterkfontein Caves in South Africa when he found bones. Among rocky rubble where miners once blasted the area were several more bones. Together, they formed the dainty foot of an ancient human ancestor called Australopithecus. This particular cousin is rare to begin with, but what made the find so spectacular was that the skeleton was virtually complete. However, things were not as easy as brushing all the bones into a dustpan and taking them home. It took Clarke and his team a painstaking 20 years to find, clean, preserve, and reassemble the individual. Little Foot, as it became affectionately known, died 3.6 million years ago. This makes the fossil the oldest, most complete ancestor ever found. The hominid will add valuable understanding to how the scarce Australopithecus looked and moved. Late in 2017, the University of Witswatersrand opened its doors and unveiled the skeleton to the public for the first time.[6]

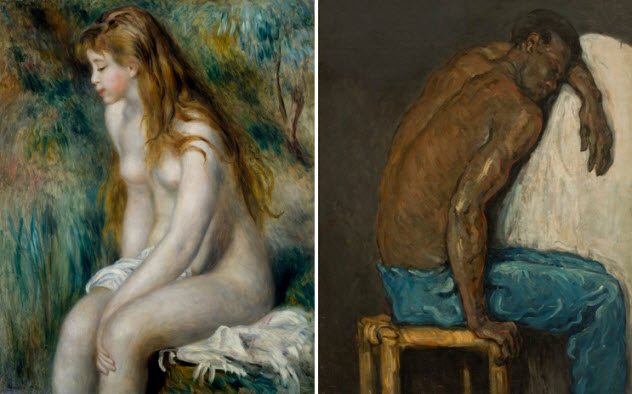

4 Monet’s Secret Collection

A firm favorite of coffee mug makers and poster producers, the French painter Claude Monet produced appealing work that still sells whatever it gets slapped on. But he did something unusual during his time. By 1890, Monet was a wealthy man, thanks to his talent with a paintbrush. But few know that he was also a serious art collector. It may sound like nothing. But during Monet’s lifetime, artists were more interested in the creations of others as inspiration than as future financial investments. Similar to his family life, Monet fiercely kept his private collection out of the public eye. He also kept no records of what he collected.[7] This made a planned 2017 exhibition of his secret batch somewhat difficult. The Musee Marmottan Monet in Paris diligently investigated all possibilities. In the end, the museum identified an inventory of 120 paintings and sculptures. He owned masterpieces from Delacroix, Corot, and Cezanne. He also collected from two personal friends, Manet and Renoir (who painted Monet’s family). Some of the works were by Pissarro and Signac, which busted the myth that Monet was against neo-Impressionists.

3 Scott’s Lost Photos

Captain Robert Scott died in 1912 during the return leg of his journey from the South Pole. His expedition is better known for tragic events, such as the four people who perished with him. In 2011, the great-nephew of one of those men published photos taken by Scott. This album was thought to be lost for over 50 years. Thus far, the expedition’s narrative had been based on images taken by another photographer, written records, and sketches. However, Scott tasked himself with the main photographic record.[8] Finally available to the public, these images reveal moments through Scott’s eyes. One photo shows a content-looking Captain Oates. However, when he developed frostbite while returning from the South Pole with Scott, Oates committed suicide. Another photo of a train of ponies being led over a hill was the last to show some of the men alive. All the ponies died. Less tragic moments show Dr. Edward Wilson, whose descendant released the snaps, sketching the mountains. The hut at Cape Evans, dogs, impressive scenery, and team members all capture the preparations, teamwork, and scientific studies that often become forgotten in the more dramatic elements of Scott’s story.

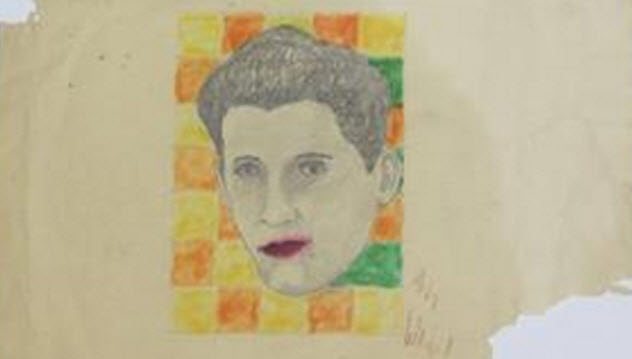

2 Warhol’s Childhood Art

In 2010, a businessman visiting Las Vegas bought five paintings for $5. At some point, Andy Fields decided to reframe one of the pictures. It was then that he discovered a sketch hidden in the back. Drawn in a childish hand was a man’s head against a background of blocks. The face was identified as Rudy Vallee, a singer from the 1930s. The portrait was believed to have been drawn by Andy Warhol when he was 11 years old and suffering from chorea. He drew Vallee in pencil before adding the pop art nuances that eventually became his signature style. Most apparent were the bright red lips, and in this case, Vallee wore real lipstick. The blocks, done with green and orange felt-tip pens, were another pop art motif. Warhol’s work is globally recognized as a dramatic shift in the history of art, and the sketch represents the roots of this movement. The world received its first view of Warhol’s earliest-known creation in 2012 when it was displayed at a Bristol gallery. At that time, the colorful picture was valued at approximately $2 million. But here’s where it gets interesting. Shortly after the headlines erupted about this newly discovered childhood sketch worth millions, some experts on the artist’s work began to deny that it was a Warhol. They said that it didn’t look like his work and pointed to inconsistencies in the story of how the sketch was made and found. Supposedly, Fields had contacted the Andy Warhol Authentication Board and they said that the work was not by Warhol. Even Warhol’s own brother claimed the sketch was a fake. But the most convincing piece of evidence? Warhol was 11 years old in 1939. Felt-tip pens had not yet been invented, so how did Warhol sketch Rudy Vallee in 1939 with felt-tip pens?[9]

1 Bones Of Saint Peter

A box with human bone fragments is somewhat of an embarrassment to the Vatican. Said to be the mortal remains of Peter—apostle, saint, and first pope—the box was opened during mass for the first time in 2013. In St. Peter’s Square, Pope Francis held the relics aloft and revealed eight bones tied to an ivory base. Though he handled the container with respect, Pope Francis did not say anything. This is because the Vatican is not wholly convinced that Saint Peter is in the box. The 2.5-centimeter-long (1 in) pieces were unearthed in the 1940s from a tomb under St. Peter’s Basilica. They belonged to a man in his sixties. In 1968, an archaeologist found Greek graffiti near the grave, translated it as “Peter is here,” and subsequently convinced Pope Paul VI that they might have found the saint. Other archaeologists did not agree with the interpretation, and neither did the Vatican at large. While conceding that the relics could belong to St. Peter, Vatican officials go no further than to say that the bones are only “traditionally recognized” as the saint’s.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages