Hard for humans to pronounce, with a deep glottal stop after the first “A”, the Aalaag conquered Earth easily to set the stage for Gordon R. Dickson’s 1987 novel, Way of the Pilgrim. Considered within their own ethos, the Aalaag are extremely just masters — mistreatment of their human “cattle” by one of their kind is a serious offense. But they demand obedience and a rigid code of conduct that rankles the human spirit. Actually, the Aalaag are a conquered race themselves, fleeing from some unnamed but awesomely powerful enemy that took their home worlds. They are in essence warriors, tall and proud, each with a collection of personal arms and possessing a Spartan outlook on their condition. Every single Aalaag views duty as the highest virtue, and all duty is directed towards one day regaining their lost worlds. The races they themselves conquer are used to exploit resources in support of this ultimate goal. Our hero is Shane Evert, a gifted linguist who leads a translator-courier corp in the service of the alien leader, First Captain Lyt Ahn. The book title refers to the use of a Pilgrim as a universal motif of the human condition, which becomes a symbol for the nascent resistance movement. Absorbing, warmly human — at times captivating — the novel is Dickson at his finest, and that is a high level of writing indeed.

Forget about the absolutely wretched John Travolta movie. Forget about whatever you think of L. Ron Hubbard as the founder of Scientology. Just read his mammoth (1,066 paperback pages) 1982 novel Battlefield Earth. It is rollicking space opera the way space opera is supposed to be. The Psychlos don’t just conquer planets. They don’t just conquer galaxies. They conquer universes. Only they have the secret to instantaneous teleportation. And one of their biggest operations is the Intergalactic Mining Company, which knocks natives back to the Stone Age and then systematically strips their planet of all available ore, almost down to the very core. Oh, and the Psychlos find cruelty to be “delicious.” The crooked — even by their standards — Security Head of Earth is named Terl and he is scheming to get rich by “training” native humans to do some illegal mining for him. Superb characterization of both aliens and humans in a story that moves so briskly, you’ll forget you are reading. A tip of the hat must be made to the Selachees, another alien race in the book that is unique and crucial to the outcome.

Alan Dean Foster has penned a number of works set in the Human-Thranx (Humanx) Commonwealth, but most deal with well-known characters such as Flinx and Pip, with the Thranx being in the background if appearing at all. One novel, however, thoroughly explored the culture of the Thranx while detailing how humans came to partner with them. That would be 1982’s Nor Crystal Tears, which in large part is written from the Thranx viewpoint. Everything just seems to fit in this novel — by the end of it, you are so much pulling for the insectoid Thranx to form an alliance with humans that you would immediately recognize any instance of Foster not treating a Thranx as a Thranx (even though there is plenty of room for individualism within the species). But he handles the race perfectly. And I happen to really like praying mantises.

Specifically, the Martians in Fredric Brown’s 1955 novel Martians, Go Home. They literally are little green men, but what they truly are — first, foremost, and always — are assholes. Being an asshole seems to be their major occupation. They invade Earth by the millions literally overnight, speaking English with something like a Brooklyn accent, and proceed to make utter nuisances of themselves. With disastrous, even fatal, results. They can teleport anywhere, and although they can’t be touched, they are substantial enough to where you can’t see through them — auto and plane crashes by the thousands. They like nothing better than to tell you who your wife is sleeping with, give national defense secrets to other countries, comment of human shortcomings — anything to be as big a pain in the ass as possible. This book is almost universally considered a classic of the genre, and I haven’t met anyone who read it and didn’t like it. Speaker for the Dead is Orson Scott Card’s 1986 sequel to his justifiably world-famous novel Ender’s Game (a deserved entry on JFrater’s list of science fiction for people who don’t read science fiction). Both novels won both the Hugo and Nebula awards — the first time anyone has accomplished such a back-to-back feat. Speaker is much different in tone, backdrop and subject material, even though Ender is still the major character. Almost certainly many people will disagree with listing pequinos as a classic alien race — arguing instead for the Buggers or even Jane — but it is the rich depiction of the “piggy” society that gets the nod here. Especially because, much to Ender’s chagrin, once again the difficulties of interspecies communication are at the forefront as humans attempt (in vain) to understand the pequinos without disrupting their natural development. Very touching in places, and a must for any sci-fi reader interested in comparative religion. Before that scares you off, I am most decidedly NOT interested in such, but loved the book anyway. If nothing else, the concepts of framling (humans from other planets), ramen (non-humans whom we communicate with as though they were human), and varelse (non-humans with whom no communication is possible, such as intelligent viruses) should be remembered at the inevitable time when we come into contact with interstellar beings.

Widely included in university science fiction courses everywhere, Arthur C. Clarke’s 1953 classic Childhood’s End depicts yet another conqueror of Earth — but a benign one, in many ways. The Overlords make life better for everyone and end many of our persistent woes, all while sitting aloof in their gigantic starships positioned over major cities. Mankind adapts, as is his nature. But the Overlords will not reveal themselves for fifty years and the reason why incorporates the Jungian concept of racial memory. No spoiler coming, but this inclusion is probably why so many professors love to teach the novel. Anyway, of course there is a secret to why the Overlords are doing what they do. What happens when that is revealed might best be described as “poignant.”

Larry Niven didn’t need the money but Jerry Pournelle did. Doesn’t really matter, because both guys are science fiction authors whether they’re eating Hamburger Helper or fillet mignon. Together they are one of the most successful collaborations the field has ever seen. 1985’s Footfall is an excellent example. People who don’t read science fiction were reading Niven/Pournelle novels in college during the 80’s while waiting for the next Heinlein to come out. Anyway, anyone who has read the book has to think of the Fithp as elephants. As humans are a culture of individuals, as ants are a colony culture, the Fithp are a herd culture. Excellent treatment of that basic premise — and being herd creatures, they do not understand the concept of diplomatic compromise… you either dominate or you submit. In particular, the internal politics of an intelligent herd engaged in difficult conquest are handled with admirable skill.

Ok. So a guy publishes a novelette and it wins the Nebula — mere months after the guy publically denounces the awards themselves! Then it wins the Hugo. Along with the John W. Campbell award because, after all, the guy is new. So he’s the first person ever to win all three of those awards in one year. Big deal? Sort of. Along came Hollywood and a somewhat underrated film starring Dennis Quaid and Louis Gossett, Jr. (Gossett got a Best Actor nomination, even though the film wasn’t really a hit.) Suddenly, Barry B. Longyear is a major player in science fiction as a result of 1979’s Enemy Mine. Drac and humans are at war. One human fighter pilot and one alien fighter pilot are marooned on a world where existence is difficult to say the least. They are forced to pool resources just to stay alive. Problem is, the Dracs are hermaphrodites and Jeriba doesn’t need a partner to reproduce. Spoiler alert next sentence: An untimely death and our human is forced to raise the alien progeny as his own. Both the book and the movie are essentially the story of one human and one alien interacting, with a beginning and an ending tacked onto either end. If you’re in the right frame of mind, you’ll cry. You will absolutely know the Drac, especially if you have both seen the movie and read the book. The Drac are included here because they fit the criteria; I own many Longyear books mainly as a result of the sheer pathos in Enemy Mine, but find the majority of his stuff barely readable.

H. Beam Piper solidified his place in science fiction history with the publication of 1962’s Little Fuzzy. The adjectives most used in reviews of this book might well be “delightful” and “charming” and one can’t blame the reviewers for that. Cute and cuddly, the Fuzzies are. But the novel explores a rather important theme: how do we define sapience? Is this lifeform just a critter, over which we can claim dominion, or a thinking creature in its own right, in which case exploitation — and even murder — rears its ugly head? Sequels followed, not always written by the originator — none are as enjoyable as the original.

It’s problematical whether Keith Laumer is best known for his Bolo series of works or what he has done with his James Bond-ish assistant diplomat character Jame Retief. Probably the latter. Lots of stories and novels over several decades. Regardless, these tongue-in-cheek tales of derring-do and human ingenuity in the face of human diplomatic incompetence have sold quite well for many years. In most of them, there is an insidious plot behind whatever the current weird aliens are doing that is being masterminded by the Groaci. No slouches at the diplomatic bargaining table, the Groaci are nonetheless almost incapable of dealing squarely. The books are pun-filled and light-hearted, but the Groaci are badass unless put on a leash. Almost not included on the list, as they are rather a two-dimensional race. Fun, nonetheless.

Poul Anderson is undoubtedly one of the deans of American science fiction — his word count alone contains way too many commas. Many of those words were as a result of cranking out short story after short story for the magazines back in the day. He had sort of a “Future History” — a term associated with Robert A. Heinlein which see, — but Anderson’s future history was rather a disjointed one. Many of his stories were set in the backdrop of the so-called “Polesotechic League” which spanned 4,000 years of human interstellar exploration. The League is a thinly-veiled (if veiled at all) allegory of 19th-century robber-baron capitalism. So what about the Ythri? 1978’s The Earth Book Of Stormgate violates a criterion: it’s a story collection, not a novel. But Hloch of the Stormgate Choth introduces each story as a scholar/historian. And the interwoven stories themselves, combined with Hloch’s notes, definitely give the reader a sense of Ythrian culture. The best way to include that race in this list — and they are worthy of inclusion — is via the Earth Book (although Ythrians also appear in other works by Anderson).

Hard to explain these guys without spoiling everything, but I’ll try. Well over half of Robert A. Heinlein’s 1954 “juvenile” SF novel The Star Beast has played out before the word Hroshii ever appears. But, they’re plenty powerful — and disinclined to negotiate. They’re looking for someone, and they simply will not take no for an answer. The someone they are looking for has a little trouble taking no for an answer, as well. Not truly disobedient, and with no desire to cause harm, just kind of literal-minded in following instructions and always a little hungry. “Lummox” is so a person and more than that, s/he’s a friend!

Pretty danged human for being essentially giant spiders. Canadian author Robert J. Sawyer, who is probably today’s foremost purveyor of “hard” science fiction, introduced us to this race in 2000’s Calculating God. Even though the events in the novel deal with the Forhilnors coming to Earth and interacting with a human paleontologist, it could be said that the aliens are simply bystanders… Sawyer uses that encounter to tackle really mind-blowing concepts of creation, cosmology, and why life exists at all. Nevertheless, the reader would love to have Hollus as a dinner guest and would be proud to have that [person] as a friend. Satisfies the criterion of knowing what those folks are really like. But as a digression: Take three good friends. One is a fundamentalist assured of his salvation. The second is an agnostic who feels he believes in God but doesn’t quite know what that means. The third is an atheist who looks strictly to chemical processes. Remember, they are all good friends. Calculating God is the book they should discuss around a campfire.

If you don’t know David Gerrold, you nonetheless probably know one thing he did — he wrote the Star Trek episode “The Trouble With Tribbles.” His output includes a number of short stories and novels of varying quality. But in 1983 he published A Matter For Men, volume one in what became known as “The War Against The Chtorr.” Although the “worms” are the most visible face of the Chtorr, what we have here is nothing less than the attempt of an entire biosphere to conquer Earth. Several books resulted, and happily some of the latter ones are just as good as the first. They really have to be read in order, though, as the Chtorran infestation multiplies and human reaction changes accordingly. This comes close to violating a criterion — it would be stretching it to call a Chtorran worm a “person”… even with absolutely zero speciesism. A God maybe, but not a person.

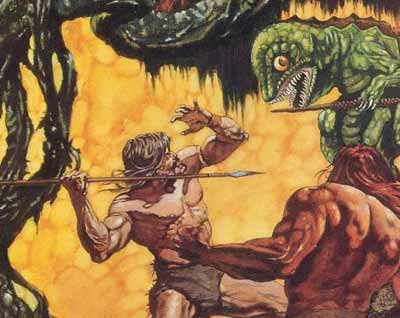

Another rather well-known race, and here’s hoping someone with a real budget will get around to making a movie of Harry Harrison’s 1984 masterpiece West of Eden. It spawned a few sequels (with the usual slight lowering of quality) and is a stunning example of meticulous alien-creation. Although, the Yilane aren’t truly aliens in one sense of the word… this is an alternate evolution of Earth story. Humans are at the hunter-gatherer stage. The Yilane are 4-foot tall, erect intelligent reptiles descended from dinosaurs. Theirs is a matriarchal society whose technology is based almost exclusively on the manipulation of the biological sciences. They literally grow plants and animals that are modified to perform such diverse functions as microscopes, boats, and living blankets. The Yilane are tropical whereas the humans are temperate. But impending climate changes push the two societies towards one another and conflict erupts. Kerrick, the human protagonist, is uniquely situated — he was captured by the Yilane at an early age and raised among them. This upbringing is the true beauty of the book: it allows the author to show the reader the awesomely rich Yilane culture without having to rely heavily on exposition. As Kerrick learns, so do we. And quite an education it happens to be, as readers end up truly knowing a completely alien culture — without any sacrifice in good storytelling whatsoever. Harrison is rather erratic in the quality of his various works — some are horrible, many are craftsman-like, a handful are quite good — but he undoubtedly triumphed with this one. Contributor: Grubthrower