10The Liver Jar

When an uncle died, a family that wishes to remain anonymous inherited a lump of stone. For the next 20 years, the terracotta pot did garden duty as an ornament, occasionally forgotten in the shed. One day, somebody realized the capsule-shaped rock had a rather Egyptian face. Removing the Pharaoh-resembling relic from its perch on a Dorset patio, it was taken for evaluation. Surprisingly, what the family thought was just a decorative ornament, turned out to be a 3,000-year-old artifact from ancient Egypt. The face, despite sporting the iconic headdress, was not a Pharaoh, but the god Imseti. The deity had the unglamorous task of protecting livers removed from corpses until the dead would need it back in the afterlife. The 13-inch-high vessel was designed to hold the organ. Called a Canoptic funerary jar, the internal organs of the deceased were placed in several such pots. It remains unknown how such an old Egyptian Canopic jar (thankfully lacking a liver) came into the possession of the said uncle in England.

9The Janus Cup

Another human-faced relic was forgotten in a box for nearly a lifetime. John Webber from Dorchester, England, was given the cup by his grandfather. The senior Webber was a scrap metal dealer who bought and sold mostly bronze and brass. Believing that it was wrought from those metals, his young grandson stowed it away under his bed. In his 70s, John Webber rediscovered the small gift from his grandfather while he was preparing to move house. Realizing that the 5½-inch (14 cm) cup was not brass or bronze, he approached the British Museum. The experts there were baffled and declared they had never seen anything like it before. It featured the double-faced Roman god Janus, his forehead decorated with braids and twisting snakes. On their suggestion, Webber shelled out a stiff amount to have the metal tested at a laboratory. It turned out to be gold dating back to 3rd-4th century B.C. and that the artifact was forged in the ancient Persian empire of Achaemenid. The ancient god of gates certainly opened a lucrative door for Webber—it recently sold for $100,000 at an auction.

8The Pizza Base

A different sort of pizza base raked in a million pounds for Sotheby’s, the auction house. Near the bathrooms of Ask Pizzeria in North Yorkshire, a wooden stand patiently awaited rediscovery. Eventually, someone thought to send a photo of the giltwood carving to Mario Tavella, Sotheby’s furniture expert. He immediately recognized the decorative theme of naked youths and garlands as the missing base of a cabinet he had personally been searching almost 20 years for. The 17th-century Roman baroque cabinet lost its stand sometime after World War II, and hopes of ever finding it again waned with every passing decade. The fully assembled cabinet shows an elaborate motif of a crowd being blessed in Rome by the Pope. Why the base initially vanished or how it ended up being owned by a couple in the restaurant business might never be discovered. One clue to its origins comes from similar stands, near-identical pieces in Denmark believed to have been gifts from Pope Clement IX.

7The Ding Bowl

A family from New York state decided in 2007 to visit a yard sale near their home. Browsing the items on offer, they noticed a $3 bowl. There was nothing spectacular about the white, unassuming vessel but they bought it anyway. Not knowing the immensity of what had just occurred, they took it back home and displayed it in the living room for years. At one point, they became curious about its age and origins. The assessment report returned with a shock. The five-inch diameter vessel with its simple, leafy design was a 1,000-year-old Chinese artifact worth up to $300,000. Called a “Ding” bowl, it is one of the finest examples of Northern Song Dynasty ceramics, and exceptionally rare. The well-preserved antique matches only one other in size, shape, and decoration, and that bowl arrived at the British Museum sixty years ago. The family was in for a second shock when Sotheby’s auctioned off the item. Despite being valued at $300,000, four bidders tenaciously fought for the Ding bowl until a London dealer won it for $2.2 million.

6The Sleeping Lady

Art historian Gergely Barki wanted to cheer up his bored daughter when he switched to a channel showing the movie Stuart Little. It was Christmas Day in 2008. The decision led to the highlight of his career. While watching, his experienced eye caught a painting hanging in the background of the movie set. It turned out to be a missing Hungarian masterpiece. As Barki followed the trail, it became clear that the painting, Róbert Berény’s Sleeping Lady with Black Vase, passed through the hands of several owners, never realizing its worth. In the middle 1990s, an art collector paid $40 for the work after discovering it at a charity auction in San Diego, probably as a donated piece. A Hollywood set designer bought it from the collector for $500, and by the time Barki contacted her about ten years later, it was hanging in her home. A Berény can demand around $120,000 today. The art deco painting depicts the artist’s second wife Eta, who was an accomplished cellist. Before vanishing, it was last seen in Hungary when it was sold at an exhibition in 1928.

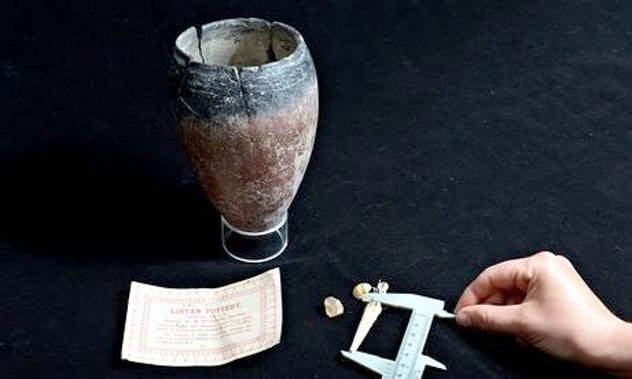

5The Petrie Pot

In the 1950s, a man owed a taxi driver some fare. Instead of counting out the bills, he handed the driver a little pot. A card attached explained it was “Libyan Pottery” from 3,000 B.C. and was discovered by Professor WM Flinders Petrie, in 1894-5. The English taxi driver, Charles Funnel, accepted. The black and red vessel was only rediscovered in 2014, when a grandson, Guy Funnel, was clearing his father’s garage in Cornwall. Recognizing the 19th-century archaeologist’s name on the cardboard label, he contacted the Petrie Museum in London. It was a rare pot with a fascinating history. It was not Libyan, but Egyptian, one of the few times when the ace archaeologist made such a blunder and said so in public later on. The card is valuable because it shows how artifacts were distributed to individuals on a systematic scale not guessed at before. Commercially printed, it remains the only one ever found. The unidentified taxi passenger might have been Joseph Milne, a museum curator from Oxford who met Petrie in the 1890s. Milne owned a bowl from the same grave that produced the Funnel pot.

4Roman Mortarium

Ray Taylor was in his garden when he happened upon a flat bowl. The Alcester resident examined the clay vessel and thought he would treat the local birds to a bath. Feathery visitors used the bird bath for the next few years until Taylor’s daughter saw similar artifacts on display at the Roman Alcester Heritage Museum at Globe House. Acting on her suggestion that he take the piece to the museum, Taylor was amazed to learn his improvised water bowl was a 2,000-year-old Roman artifact. It was identified as an A.D. 2nd-3rd-century mortarium, a tool that much served the same purpose as a modern mortar and pestle. Ingredients such as herbs and spices would have been ground to a finer quality inside of it. A mortaria pottery production center once existed in Mancetter, close to Atherstone, and that is likely where this utensil was fired. The fact that it is complete and in good condition makes it extraordinary. Most such finds were discarded in Roman times as broken trash. After finally understanding the rarity and worth of what he had found, Taylor kindly donated it to the Warwickshire Museum.

3The Leicester Stone

When a garden ornament went up for sale in Leicester, one customer immediately saw what the owner could not—potential. James Balme, archaeologist and TV presenter, could not identify with certainty what the pillar-resembling item was. However, instinct told him the heavy stone was not merely a lawn trinket, and so he purchased it. After cleaning it, Balme realized the markings on the artifact resembled a complex enough pattern to perhaps represent writing. Only the front side is adorned in this manner. The 55-65 pound (25-30 kg) sandstone block tapers more narrowly towards the top and is about 18 inches (46cm) high and 5.5 inches (14cm) thick. What it was used for remains an uncracked mystery, but Balme speculated it might be a keystone from a ceiling or archway. Who carved it and when are two more questions needing solid answers. While not a done deal, it is possible that it was masoned sometime between the 5th-11th centuries during the Anglo-Saxon period. During that time, different cultures created notably complex stone art.

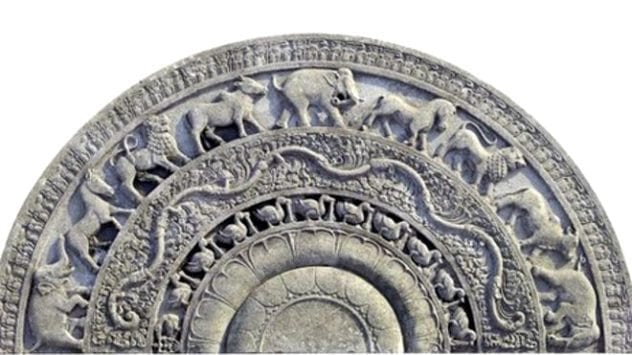

2The Devon Moonstone

In 1950, a four-year-old girl moved into a Sussex home her family had bought from a Sri Lankan tea farmer. On the property was a hefty stone weighing almost a ton. They took it with them whenever they moved. Kept in the garden, they remained blissfully unaware of the true nature of the exquisitely carved 4ft by 8ft (1.2 – 1.5 m) slab. By the time the girl was grown and married, she still had the stone she used to play with. Now living in Dorset, Mrs. Hickmott invited an auctioneer from Bonhams to have a look at the curious surface bearing Brahim cows, elephants, birds, horses, and lions. Used to mark the end of her garden path, the granite relic was eventually identified as a Sandakada Pahana, a Sri Lankan moonstone. It is very similar to moonstones at temples built during Sri Lanka’s Anuradhapura era (400 B.C.-A.D. 1000). Archaeologists from its native country cannot decide if the artifact is authentic, nor can they find any record of its removal from the Anuradhapura district where records were kept since 1890. To find a moonstone outside of Sri Lanka is highly unusual and Bonhams estimated its worth at more than £30,000 ($47,500).

1Blenheim Sarcophagus

In 2016, an antiques expert was strolling through the gardens of Blenheim Palace in England when he noticed a flower pot. Rather, something large and ornate that was being used as a tulip bed. Drawn closer by the familiarity of the scene depicted on the marble surface, he noticed exquisitely carved figures. Dionysus, Hercules, and Ariadne were shown in a festive mood, along with animals. He informed Blenheim Palace, the ancestral home of the Dukes of Marlborough, that their rock garden feature was, in fact, an ancient coffin. The partial Roman sarcophagus is lacking its bottom, sides, and back. Even so, it remains an impressive fragment—it weighs around 550 pounds (250 kg), stretches six ft (1.8 m) long, 2.5 ft (80 cm) high, and has a thickness of about 6 inches (15 cm). It took six months of careful restoration to reveal the elite artwork. Regrettably, the sculptor is unknown, and there is no way to know who the 1,700-year-old casket was for. The expert who identified it also assessed its worth at about $121,000, but Blenheim Palace decided not to sell the antique that landed in the gardens sometime during the 19th century. It can now be seen inside one of the hallways. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages