When the storm struck on September 8, waves measuring 4.5 meters (15 ft) covered the island of Galveston in water, and in just a few hours, winds moving at 215 kilometers (135 mi) per hour turned Texas’s largest city into a pile of rubble. After the nameless cyclone finally moved on, it left bloated bodies and shattered lives, but it also left behind survivors determined to rebuild and numerous stories about that fateful day.

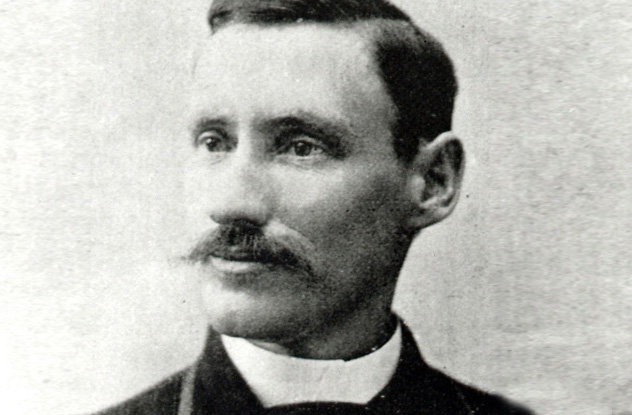

10 The Strange Tale Of Isaac Cline

The story of the Galveston Storm starts with a man named Isaac Cline. Chief of the US Weather Service Bureau in Galveston, Cline was a prominent figure in the meteorological community and championed scientific methods over instinct and intuition. However, Cline thought he knew everything there was to know about hurricanes, famously saying that it was impossible for a tropical storm to destroy the city. In fact, he was so adamant that Galveston was safe from hurricanes that he successfully opposed a motion to build a seawall that would’ve protected the island from giant waves. Isaac Cline was dead wrong, and so was everybody else in the US Weather Bureau. When American meteorologists learned about the oncoming storm, they predicted it would swing toward Florida because they thought it scientifically impossible for hurricanes to head south. Ignoring the warnings of Cuban forecasters, Cline and his associates turned a blind eye to the cyclone right until September 7. Then Isaac started getting a little nervous. For days, his brother Joseph had insisted that the storm was heading their way and demanded that Isaac call for an evacuation. The elder Cline ignored his younger sibling’s advice, but when the weather took a turn for the worse, he decided to take action. In defiance of US Weather Bureau protocol, Isaac raised the hurricane warning flags without permission from the D.C. office. However, few people took notice, and by September 8, it was too late to evacuate the city. What happened next is a matter of dispute. With the hurricane on the horizon, Cline said he jumped into his buggy and rode around town, warning everyone to take shelter. However, some historians dispute his claim as no one else reported Isaac’s actions. Either way, it was too late. When the hurricane hit, it hit hard, sending waves and debris crashing through the streets. Isaac and his staff stayed at his office, sending Washington the latest news and pleading for help until the telegraph wires went down. With nothing left to do, Isaac fought his way toward his home, trudging through the quickly rising water. When he reached his house, he found that his pregnant wife and three daughters had invited 50 neighbors to seek shelter. But Isaac’s allegedly storm-proof house was no match for the fury of nature. The hurricane flung a railroad trestle into Cline’s home, knocking it over. Isaac, his friends, and his family were dragged into the rising flood. Cline managed to save one of his children, and Joseph rescued the other two, but Isaac’s wife didn’t make it out alive. When the storm finally cleared and the city was rebuilt, Isaac moved his family to New Orleans. He lived there until his death in 1955, but he could never escape the shadow of the decisions he’d made in Galveston.

9 The Tragedy At Ritter’s Cafe

As the storm made landfall, people didn’t understand how much trouble they were in. Parents let their kids run and play in the flooded streets. Feeling invincible, businessmen continued their meetings and went to lunch with their associates. Several ended up at Ritter’s Cafe, one of Galveston’s most iconic restaurants. But as wind pounded on the walls and rain slammed against the windows, people started getting edgy. That’s when the storm ripped off the cafe’s roof. Exposed to the elements, the building’s second story filled with wind, bending the walls and collapsing the beams. Making matters worse, the second floor wasn’t a cafe but a printing shop full of giant, wooden presses. So when the first-floor roof cracked, tables, desks, and machinery plunged into the dining room below. A few diners managed to duck under a solid oak bar, but the rest of the patrons weren’t so lucky. Five were crushed to death, and another five were badly injured. Hoping to get help, a waiter ran outside looking for a doctor, only to be swept away in the floods.

8 Animals Of The Galveston Storm

Humans weren’t the only victims of the 1900 storm. Plenty of animals suffered tragic fates as well. One horse was trying to escape the winds only to have a piece of wood shoot through its body, killing it instantly. After the hurricane passed and the city was left in ruins, Galveston’s dogs literally went insane due to lack of food and water. Some animal stories ended more happily. Despite the gales, one woman held on to her pet parrot and managed to keep the bird above the rising floodwaters. Ida Smith Austin, a Presbyterian Sunday school teacher, brought her cow into her dining room. Some animals, meanwhile, figured out how to get inside buildings all by themselves. Multiple witnesses described a panicked horse that kicked down a house door and made its way upstairs. Two days later, rescuers found the animal terrified but alive. Not all the animals in Galveston were cute and cuddly critters. As water rushed down the sidewalks, people scrambled into nearby trees, hoping to wait out the storm in the branches. Wanting to escape the flood, venomous snakes also slithered up the trunks, only to find their hiding spots filled with humans. Things didn’t end well. After the storm, search parties where shocked to find stiff bodies hunched up in the trees, covered in puncture wounds.

7 The Bolivar Lighthouse

If you visit Galveston Bay, you’ll see the Port Bolivar Lighthouse, a 35-meter (116 ft) tower erected in 1873. Today, the lighthouse is dark and empty, but back in 1900, it played an important role in the seaside community. Galveston was a hotspot for European immigrants and the world’s biggest cotton port, so the lighthouse was crucial in guiding commercial ships in and out of the bay. It also saved the lives of over 100 landlubbers that terrible day in September. During the late morning, a train from Beaumont, Texas was waiting at Port Bolivar for the Galveston ferry. If everything had gone according to plan, the passengers would’ve boarded the boat and sailed across the bay, over to Galveston Island. But by this time, there was too much wind and rain, and the ferry captain couldn’t reach the shore. Realizing things were getting hairy, the engineer threw the train into reverse only to discover floodwaters had crept over the tracks. The Beaumont passengers were stranded. A train isn’t the greatest place to ride out a hurricane. Soon, water was seeping into the cars and rising up to the level of the seats. Terrified, a small group of passengers spotted the Bolivar lighthouse and decided an iron and brick building was probably safer than an unstable locomotive. The little band took off into the storm, wading through the water toward the tower. There, lighthouse keeper H.C. Claiborne and his wife were operating the broken light machinery by hand. In total, 125 people—some from the train, some from nearby homes—took shelter in the Bolivar lighthouse. When water started filling the tower, the refugees had to climb up the stairs for safety. All night long, the hurricane battered the lighthouse, causing the structure to sway back and forth. For 50 hours, the survivors were stuck inside without food and water until rescuers arrived. But at least they were alive. The 82 people who stayed on the train all died.

6 The Incredible Survival Of Mrs. Heideman

Eight months pregnant, Mrs. William Henry Heideman was hunkered down in her home when the storm ripped her house apart. Panicked, the Heideman family fled, and Mrs. Heideman escaped right before her home crumbled into the water, crushing her husband and three-year-old son. She was still in danger. The streets were completely gone, totally covered with water, and the pregnant mother was forced to scramble onto a floating rooftop. For a little while, Mrs. Heideman sailed along on her impromptu canoe until the roof smashed against an object in the road, sending her sprawling. Instead of landing in the water, which probably would’ve meant her death, the pregnant woman landed in a floating trunk. While it wasn’t exactly comfortable, it kept her above the water and safe from any passing debris. The trunk bumped into a convent, and Mrs. Heideman was pulled to safety by the nuns inside. Just a few hours later, she gave birth to a boy. And right outside the convent, unknown to anyone, was Mrs. Heideman’s brother. Hanging in a tree for dear life, he heard a child in the water, screaming for help. As the boy floated by, the man snagged the kid and hauled him into the branches. Unbelievably, the boy was the man’s nephew and Mrs. Heideman’s son, the one who’d supposedly died when her house collapsed. After the storm subsided, the fractured family was reunited, all except for Mr. Heideman, whose body was never found.

5 St. Mary’s Orphanage

Founded by the Congregation of the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word, St. Mary’s Orphanage was located 5 kilometers (3 mi) west of Galveston and run by 10 dedicated nuns who’d suffered quite a bit of bad luck. In 1875, one of the orphanage dormitories was burnt to a crisp, and later that year, a storm damaged the buildings again. No lives were lost, and the devoted sisters continued caring for the island’s orphans. Then the cyclone showed up. In 1900, the sisters were watching over 93 children, many orphaned by yellow fever. Just feet away from the Gulf of Mexico, the orphanage was protected by sand dunes, but the beachside hills were no match for the sea that day. When the hurricane hit, the sisters shepherded all the children into the newer, stronger girls’ dormitory. Hoping to keep the kids calm amid the howling wind and booming thunder, the nuns led them in a French hymn titled “Queen of the Waves.” At 7:30 PM, the ocean crashed through the dunes and poured into the dormitories. The sisters hurried the children upstairs and continued to encourage them in the hymn. As the kids sang, the nuns tied clothesline around them and then lashed the ropes around their own waists. Each woman was tied to six to eight orphans. One of the survivors recalled a nun clutching two children and promising to never let go. Soon, the angry Gulf picked the building up off its base, causing the dorm to collapse. The nuns and children were sucked into the water. Everyone died except for three lucky boys who managed to grab a tree. Days later, search parties found the bodies of the nuns spread out across the island, each one still tied to the orphans. And the sister who’d promised to never let go was found tightly still holding those two kids to her breast. The nuns were all buried exactly where they were found, and today there’s a historical marker where the orphanage once stood. And every September 8, members of the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word honor the Galveston nuns and their orphans by singing “Queen of the Waves.”

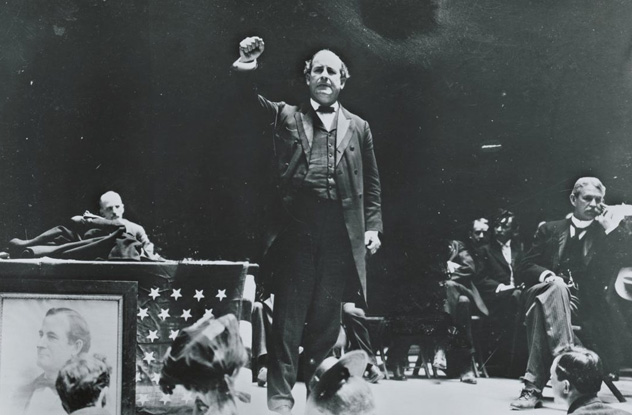

4 The Storm’s Strangest Victim

After the hurricane finished savaging Galveston, it rolled onto the Texas mainland and journeyed northward. Along the way, it plowed through Kansas and Iowa, hit Chicago, and wound its way northeast before arriving in New York. By this time, the storm had lost much of its power, with wind speeds dropping from 215 kilometers (135 mi) per hour to 100 (65 mi). Really, the biggest thing New Yorkers had to worry about was their hats. According to the New York Times, “One of the most unpleasant features of the storm was the damage that it did to headgear. Hats were whirled hither and thither.” However, hats weren’t the only casualties of the day. Before it left the Big Apple, the 1900 storm claimed one last victim, 23-year-old Charles Durfield. Not only was his death tragic, but it was also a testament to the randomness of the universe. Durfield’s demise was set in motion when Republican president William McKinley decided to run for a second term. Against him, Democrats nominated famous politician and future Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan (who’d later prosecute John Scopes in the famous “Scopes Monkey Trial”). As part of Bryan’s campaign, his staff covered New York City with gigantic signs promoting his candidacy. These signs measured 5 square meters (56 sq ft) and were held up on iron poles. They were difficult to miss, something Charles Durfield would find out the hard way. This bookkeeper from Birmingham, Alabama was vacationing with his brother and friend, and after a pleasant trip to Niagara Falls, the trio decided to stop by the city that never sleeps. So on September 12, Durfield and company were headed down Broadway when the storm showed up. At the same time, the superintendent of the Mutual Reserve Building was getting really worried about the huge “Bryan and Stevenson” sign on the nearby street. Fearing the iron poles would snap in the wind, he tried climbing up the posts to cut down the banner. Then he heard an ominous crack. A fierce gale broke the poles in half, and the gargantuan sign toppled to the ground, swallowing up streetcars, horses, and horrified citizens. If Charles Durfield had been standing a foot or two to the left or right, he might’ve escaped with just an injury. Unfortunately for the young Alabamian, he was right in the path of the pole, which pulverized his skull and crushed his neck, killing him.

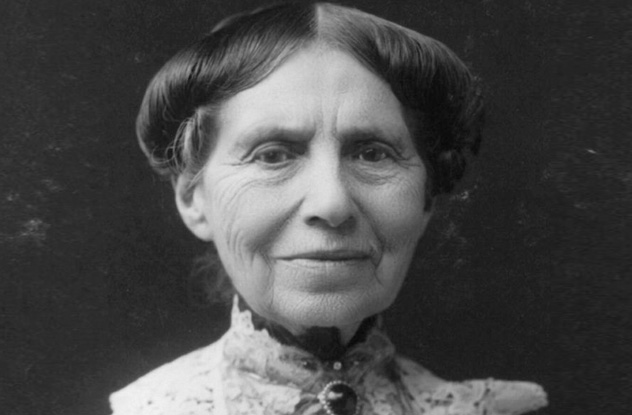

3 Women After The Storm

The 1900 hurricane totally wrecked the city of Galveston. Wind, floods, and an enormous wall of debris several stories tall mowed down over 3,600 buildings. Stunned and traumatized, the people of Galveston were not only homeless but were left without food or drinking water. On top of everything else, the mayor declared martial law and brought in the Texas militia to stop looting. The rebuilding process was going to be long and painful, but, fortunately, Clara Barton was on the way. As the founder of the American Red Cross, Barton had seen her fair share of disasters. After aiding survivors of the Johnston Flood and assisting Cuban prisoners during the Spanish-American War, Barton became a nationwide celebrity, and when she arrived in Galveston, donations from across the country poured in. Barton raised more than $120,000 to help the islanders and even acquired over one million strawberry plants for local farmers. But perhaps her most interesting contribution is what she did for Galvestonian women. She insisted that government officials put local ladies in charge of the relief effort. These were civic-minded women who’d participated in charities for years. Thanks to Barton’s insistence, they were put in places of authority and helped rebuild the shattered community. Barton wasn’t the only strong-willed woman on the island. Winifred Sweet Black was a journalist willing to get a scoop no matter what anyone else said. Originally working for William Randolph Hearst’s first newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner, Black faked illness to report on the city’s hospitals and faked her way into President Harrison’s campaign train to get an interview. When authorities said reporters weren’t allowed inside the city of Galveston, she dressed herself as a boy and managed to slip past the police barricade. Thanks to her scheme, she was the first non-Galveston journalist and only woman to report on the hurricane’s devastating effects.

2 Body Disposal

Initially, officials believed only 500 people had died in the storm, and some considered that statistic a gross exaggeration. But as more and more corpses piled up, it became clear the death toll was in the thousands. In fact, there were so many bodies that the government was having a hard time disposing of them all. There wasn’t enough room in the city morgues, and thanks to the intense Texas sun, the bodies started to rot. That’s when someone decided to drop all the corpses into the Gulf of Mexico. Groups of men, nicknamed “Dead Gangs,” were given the grisly task of digging through the rubble and loading bodies into wheelbarrows. They then hauled the corpses to the dock, where a group of 50 black men were in charge of dragging them onto ships and readying them for their last boat ride. These African Americans weren’t exactly volunteers. They were persuaded, if you will, by very convincing white men armed with guns. As compensation, everybody received plenty of whiskey to keep their minds off their dismal duties. The plan didn’t work. Just a few hours after the bodies were dumped into the sea, 700 decomposing corpses washed back up ashore. Absolutely desperate, the city made the shocking decision to stack up the bodies and light them on fire. For weeks, the survivors smelled their loved ones burning away on the beach.

1 The Entire City Was Raised

Once hailed as the “New York of the South,” Galveston was nothing more than a pile of sticks after the 1900 hurricane rolled through. If you flipped through a few old photos, you might think the city had been bombed by an enemy air force. With thousands of lives lost and nearly every building demolished, the people of Galveston were faced with a heavy decision. Should they rebuild? While some left their hometown behind, many stayed, determined Galveston would rise again. Only they had to do something about this hurricane problem. But how do you stop a wall of wind from plowing into your city? Well, you don’t, but you can come up with clever ways of dealing with the problem. First, Galveston officials decided to build a sea wall, which you might remember as something they’d earlier decided against thanks to meteorologist Isaac Cline. Over the course of 60 years, engineers built a 5-meter (17 ft) wall that stretched over 11 kilometers (7 mi). However, there was still one problem. What if the waves went over the barricade? At its highest point, Galveston was only 3 meters (9 ft) above sea level. Worried what would happen if the walls failed, engineers proposed a radical idea. They would raise the entire island. First, 12 million cubic meters (420 million cu ft) of sand was sucked out of Galveston Bay and pumped through pipes into the city. Next, in a massive engineering feat, most of the remaining homes, churches, and businesses were raised up on stilts using hundreds of jackscrews. Water lines and sewer and gas pipes were propped up as well. Finally, the sand was pumped underneath all of the city’s structures, raising some parts of the island as much as 5 meters (17 ft). As one last precaution, the island was sloped in such a way that if the Gulf breached the seawall, the water would drain off into the bay. All this work paid off in 1915 when a hurricane just as strong as the 1900 monster smashed into the island. Instead of killing thousands, this storm only killed eight. Nolan Moore has taken part in quite a few hurricane evacuations including this one. It wasn’t a whole lot of fun. If you want to keep up to date with Nolan’s writing, you can friend/follow him on Facebook. You can also email him here.