Some of the symptoms of this pathological hoarding may entail holding onto books that have no value or are otherwise useless and/or collecting countless copies of the same exact book. Perhaps the most telling behavioral trait is the impulsive, continuous acquisition of books that the collector has no realistic intention to sit down and read.[1] It’s important to not confuse bibliomania, the obsessive collecting of books, with bibliophilia, which is simply the love of books. There’s a big difference between a bookworm and a bibliomaniac. Dr. Martin Sander made the distinction this way: “The bibliophile is the master of his books, the bibliomaniac their slave.” If one is unable to temper this addiction, the results can be devastating. What wild desires, what restless torments seize The hapless man. who feels the book-disease . . . –John Ferriar, “Bibliomania”

10 The Infamous Book Bandit

Stephen Blumberg, also known as the “Book Bandit,” was a man from Iowa who amassed over 23,600 books. Unfortunately, the books he collected did not belong to him. They belonged to 327 libraries and museums across 45 states, two provinces in Canada, and the District of Columbia. Blumberg was a restless nomad who was constantly on the move, but he never sold his books. He just kept collecting more and more. He was an expert at avoiding detection. He’d wiggle through ventilation ducts in ceilings and shimmy up and down dumbwaiters. One time, he was nearly crushed by a service elevator when he was attempting to climb the elevator shaft. At the last minute, he was able to squeeze into an inspection bay indention in the wall. In 1990, Blumberg was caught. A friend turned him over to the Justice Department for a $56,000 reward. The FBI had to use a 12-meter (40 ft) tractor-trailer to move Blumberg’s stash of literature (all 19 tons of it) to catalogue for inventory. Together, the books were worth $5.3 million.[2] During his trial, a forensic psychiatrist, Dr. William S. Logan, explained to the court that Blumberg suffered from bibliomania that included schizophrenic delusions. And sure enough, after 4.5 years behind bars, Blumberg was set free and immediately continued to grow his epic book collection once more.

9 Not A Recognized Disorder

Bibliomania is well-known, and it has been observed and discussed for nearly two centuries, but the American Psychiatric Association refuses to recognize it as a psychological disorder in their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.[3] Even the Oxford University Press defines “bibliomania” as simply a “passionate enthusiasm.” In psychology, bibliomania is understood and reported as an underlying symptom of an obsessive-compulsive disorder. The act of hoarding endless piles of books has been shown to have a negative impact on one’s health and interpersonal relationships when the impulsive craving to buy and hoard books overwhelms every other desire. Medical professionals prescribe similar drugs that are recommended for compulsive disorders in general, but drugs are usually not effective enough on their own. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is the most useful intervention to cure bibliomania entirely. It involves psychotherapies designed for the bibliomaniac to practice setting and achieving goals.

8 A Fatal Case Of Book Madness

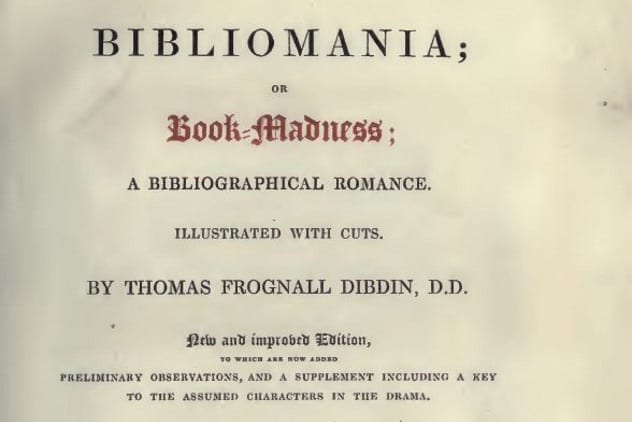

Biblion is Greek for “book,” and “mania” means madness, so “bibliomania” translates to “book madness.” The first use of this word is found in a diary from 1734 written by book collector Thomas Hearne. He wrote, “I should have been tempted to have laid out a pretty deal of money without thinking my self at all touched with Bibliomania.”[4] Back then, it was a disorder deemed to be a mild form of insanity. In 1750, there was another mention of bibliomania in a letter by Lord Chesterfield to his son that bleakly reads, “Beware of the Bibliomanie.” Finally, in 1809, a book was published by Thomas Dibdin titled Bibliomania; or Book-Madness. Dibdin wrote the book in a satirical vein about being afflicted with this odd “neurosis.” Still, it was the first time bibliomania had been examined as though it were a medical condition. He called it “the Book disease.”

7 Tsundoku

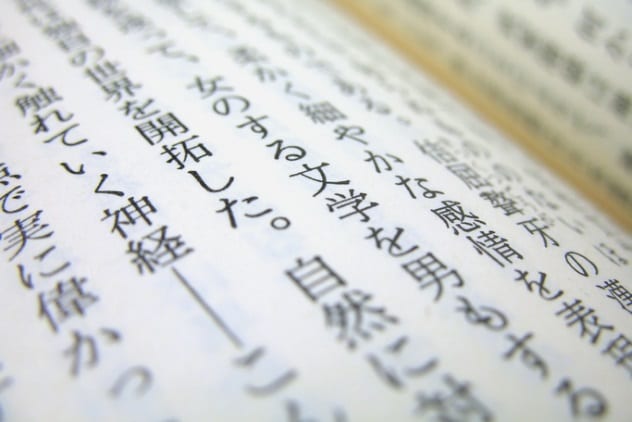

Bibliomania isn’t just a Western phenomenon. In Japan, they call it tsundoku, which refers to the act of collecting piles of books that you won’t get around to reading. Tsundoku, however, isn’t seen as a negative behavior, as bibliomania is often depicted. Instead of being perceived as an isolating, obsessive-compulsive disorder, the Japanese understand that there is, at least, a valiant intention to read the books, even though it’s not always successful.[5] According to Andrew Gerstle, a professor of Japanese texts at the University of London, the term first appeared in 1879 as a joke about a teacher who may own a lot of books but never reads them. Today, the word also applies to other facets of life completely unrelated to literature. It may explain one’s relationship with film, clothing, or even video games as “vast, untouched software libraries.” It’s a useful phrase for those habits that start with good intentions but will most likely lead to aggressive stockpiling.

6 Book Curses

Ashurbanipal was many things: spymaster, king slayer, lion killer, and king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Ashurbanipal called himself “the king of the world,” and perhaps he truly was. It’s no doubt that his empire was certainly the largest in the world. He was also a librarian in his free time and the earliest known bibliomaniac. Reading and writing was an unusual ability for kings in the seventh century BC, but Ashurbanipal was an avid scholar (when he wasn’t destroying his enemies, that is). He created the first systematically catalogued library in the world. He wanted every single book (rather, clay tablet) that he found to be added to his immense library collection. He was so obsessed that books were his favorite spoils of war. Ashurbanipal was able to collect hundreds of thousands of these tablets, but he was very protective of them. He would even write book curses to ignite fear in the hearts of possible book thieves, such as: Whosoever shall carry off this tablet, or shall inscribe his name on it, side by side with mine own, may Ashur and Belit overthrow him in wrath and anger, and may they destroy his name and posterity in the land –King Ashurbanipal[6] For some 2,000 years after the destruction of his empire, Ashurbanipal’s library lay buried beneath the rubble of his palace. In 1849, it was discovered, and within the treasure trove of words was the oldest work of literature in the world, the Epic of Gilgamesh.

5 Different Types Of Collectors

Bibliomania entails a wide variety of collectors. According to an article by Dr. Russell Belk in the Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, there’s the taxonomic collector, who longs to own every single form of a published item, and there’s the aesthetic collector, whose focus is gathering any and all books that bring pleasure. Some types of collectors are fetishistic, which Dr. Belk describes as the act of bringing together books in a way that the collector feels is making the books sacred. In the same journal, Ruth Formanek described five of the key motivations that inspire collectors. The first is simply to extend the self by the very act of acquiring knowledge. The second reason is of social import, with the goal in mind to hopefully find others to relate to and share the material with. Other collectors are motivated to preserve history and belong to the vast continuity of time. Of course, some view collecting as a means to make money, but for the bibliomaniac, it seems that the main motivation is simply addiction. All incentives for collecting are tied to a passion for the items being searched for.[7]

4 A Safety Hazard

It’s easy to be seduced by the physical presence of books, like a glorious, leather-bound hardcover, but there are legitimate risks to a bibliomaniac’s safety. The stacks will slowly weave their way through the rooms of the house, growing bulk in the kitchen, bedroom, and even the bathroom. These musky, cramped quarters disrupt one’s everyday hygiene routine because of the effort it takes to contend with a maze of precariously piled books. Tripping becomes an everyday annoyance. However, perhaps the worst offense is that old, unused books also attract rats and cockroaches.[8] These unhygienic living conditions are also a breeding ground for ants and termites. Towering piles of unread books are bad enough, but often, the bibliomaniac will end up blocking the house’s exit points. Then, it becomes a fire hazard, as books are (obviously) highly flammable. On that note, the compulsion to burn books can be a strange behavioral symptom if bibliomania becomes overwhelming to an individual. Another behavior that can happen as a result is bibliophagy, which is the irresistible urge to eat books. This, it goes without saying, comes with its own safety hazards.

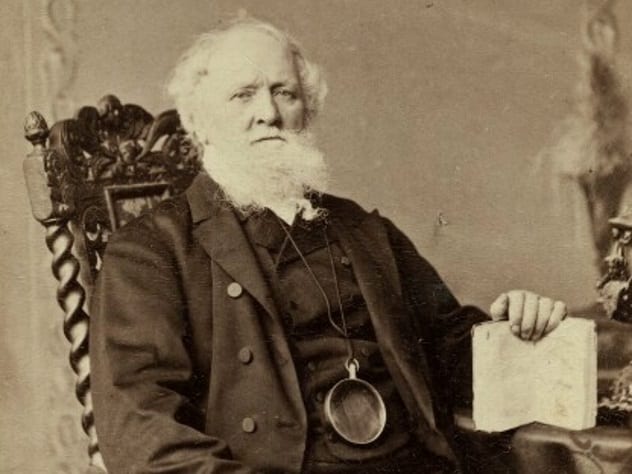

3 The Baron Of Bibliomania

Sir Thomas Phillipps was a baronet in the 19th century who was called a bibliomaniac by the rest of the world, but he referred to his condition as something even worse: vello-mania, which includes accumulating documents as well as books. Sir Thomas Phillipps knew no bounds to his obsession. In his tower, he even had a series of printers installed so that he could create more long-lasting versions of his documents. Lofty mountains of words overwhelmed his residence, with some never leaving their storage boxes. He left bills unpaid, and even damage to the house, like a leak in the roof, couldn’t be repaired because he spent so much money on his collection. A century after his death, his vast array of books and documents were sold piecemeal to the highest bidder.[9] “The largest collection of manuscript material in the nineteenth century” included 40,000 books and 60,000 manuscripts.

2 Caused By Trauma

Bibliomaniacs often become addicted to book collecting when they are very young as a way of coping with a difficult hardship. Some psychiatrists explain that bibliomania may be a defense mechanism for dealing with a serious trauma or repeated abuse, specifically. Such trauma causes sufferers to be highly skeptical about any underlying issues. They will mask their pain by piling books up all around them because they don’t want their traumatic past to be revealed. Addiction is a very common way to cope with pain. When the obsession is left unchecked throughout childhood and into adulthood, it will start to become a bigger problem.[10]

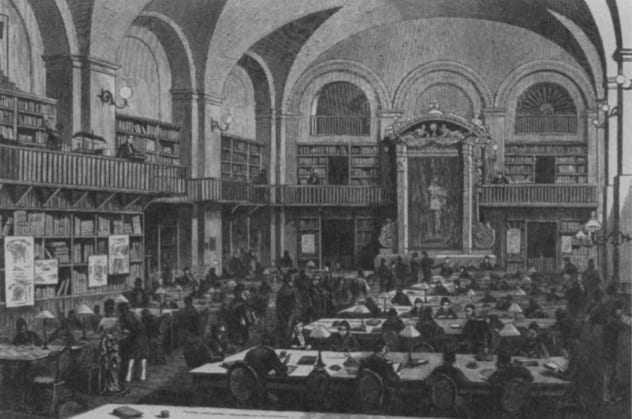

1 ‘The Extraordinary Librarian’

In 1869, Dr. Alois Pichler was given the esteemed position of “extraordinary librarian” at the Imperial Public Library in St. Petersburg, Russia. Unfortunately, Pichler’s affinity for books went beyond merely looking after them. Pichler’s first couple days of employment passed by uneventfully, but after a few months, there seemed to be a peculiar book thief in the library’s midst. A shocking number of books had been stolen from the library’s collection, and the guards suspected Pichler. He would often drop books at the exit and then rush to return them to the shelves. He also wore a large overcoat that he never seemed to take off. After two years of employment, 4,500 library books were missing. It was the grandest case of library theft ever recorded. There was no rhyme or reason to the topics, either. They ranged from texts about perfume to writings on religion. Finally, Pichler was formally accused and taken to trial. Pichler’s lawyer claimed that he was not responsible for his theft because his behavior was beyond his control. The lawyer called it a “peculiar mental condition, a mania not in the legal or medical sense, but in the ordinary sense of a violent, irresistible, unconquerable passion.”[11] It is true that a common symptom of bibliomania is bibliokleptomania, the overwhelming impulse to steal books for one’s collection. Unfortunately, claiming that Pichler was a victim of bibliomania didn’t sway the punishment in his favor. He was exiled to Siberia.