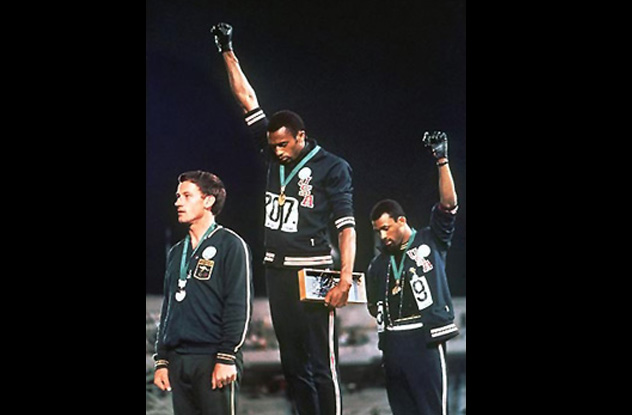

10Peter Norman

This Australian sprinter surprised many observers of the 1968 Olympics by taking the silver in the 200-meter dash. Norman finished second to American Tommie Smith and ahead of Smith’s teammate, John Carlos, setting the stage for what may be the most recognizable piece of sports photography ever. Smith and Carlos each wore black gloves and raised their fists in the air in the Black Power Salute. While Norman stands somewhat anonymously to the side, he actually played a significant role in the photo. He suggested that Smith, who was wearing both gloves before the ceremony, give the other glove to Carlos so that both men could join in the salute. Many who see the photo do not immediately notice that all three men—Smith, Carlos, and Norman—wear pins reading “Olympic Project for Human Rights,” representing a group opposing racism in sports. This act of solidarity caused Norman a great deal of trouble in his home country of Australia (he was not selected for the 1972 team despite holding the fifth-fastest time in the world), but it served as a powerful and enduring image of unity in the fight for equality.

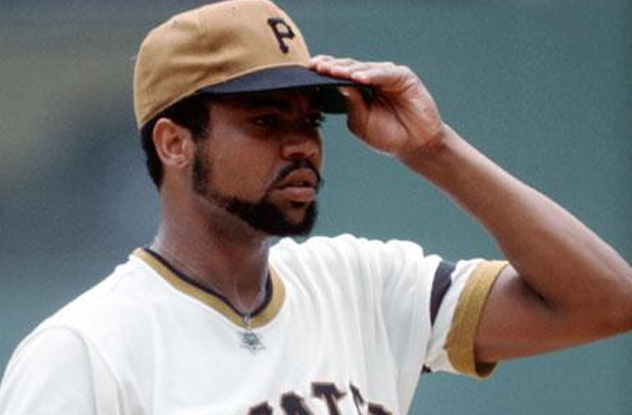

9Dock Ellis

Dock Ellis was quite a character and likely is best known for the no-hitter he threw while high on LSD. That notoriety is unfortunate given how much he accomplished as a civil rights advocate during his playing days and as a drug and alcohol counselor once his career ended. He never wavered in standing up to the injustices of inequality, and he took action as far back as his high school career, once refusing to play in game as a protest against the coach’s racism. Ellis was very outspoken, and he was never one to let someone get away with an injustice. He challenged manager Sparky Anderson to start him in the All-Star Game so that he could face Vida Blue, saying that Anderson “wouldn’t pitch two brothers against each other.” Despite some of his on-field antics—which include tying the MLB record for being hit by pitches, an act he admitted was intentional—Ellis worked diligently in charitable endeavors, most notably helping to found the Black Athletes Foundation for Sickle Cell Research in 1971. Among the many men who appreciated Ellis’s efforts in civil rights was Jackie Robinson, who wrote a moving letter praising Ellis and advising him on some of the difficulties he would encounter. Footage from a recently released documentary on Ellis shows him reading the letter, which moved him to tears even several decades after it was received.

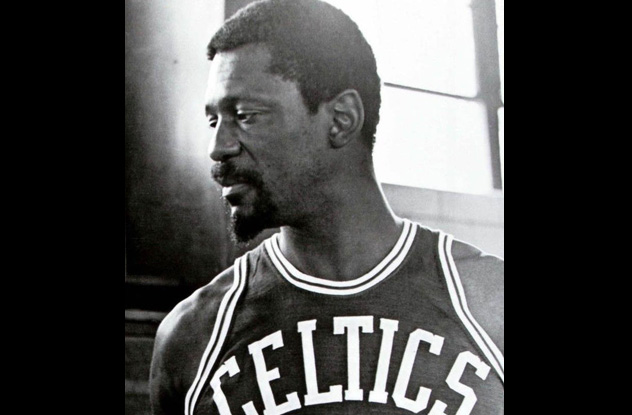

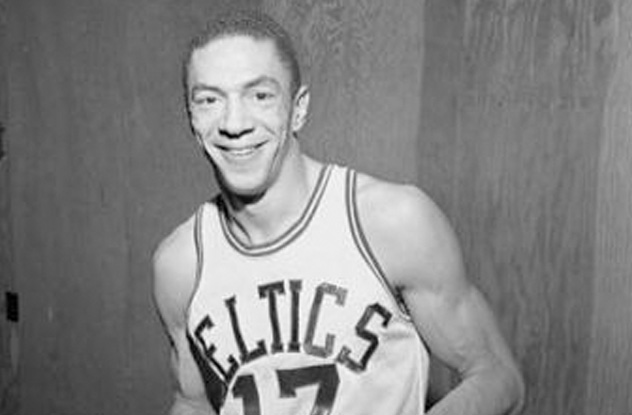

8The Boston Celtics & Bill Russell

Boston—owing perhaps to protests and riots in the 1970s after Boston public schools were desegregated by a court order—has had to endure a stigma as a racist town. But the city’s hometown basketball team, the Boston Celtics, was among the most progressive when it came to matters of race. The team was the first in professional basketball to draft an African-American player in Chuck Cooper, whom they selected in 1950. The Celtics were also the first in North American sports to hire an African-American coach when Bill Russell took over the team from the legendary Red Auerbach in 1966, a time of significant unrest throughout the country. Russell is known as one of the most successful professional athletes in history, but he has also been an outspoken advocate of civil rights, and he has recently spoken out in support of gay athletes as they endure what Russell sees as issues black athletes encountered when he played. In 2010, Russell was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, for his work as “an impassioned advocate of human rights.”

7The Starting Five At Texas Western In 1966

Texas Western’s role in the civil rights movement was something of a surprise to them, as many did not realize that they were members of the first collegiate basketball team to field an all-African-American starting lineup—and, ultimately, the first to win an NCAA Championship. In recollecting the game, most of the Texas Western players recall not understanding its importance until years later, when strangers would approach them to thank them for opening doors that had previously been shut. That championship game, played against Kentucky, took on greater significance after famous Kentucky coach Adolph Rupp reportedly declared that no all-black team could defeat his all-white squad. Pat Riley, then a member of the Kentucky squad, recalled how motivated Texas Western was after learning of Rupp’s comments, saying, “It was a violent game. I don’t mean there were any fights—but they were desperate and they were committed and they were more motivated than we were.” Ultimately, Texas Western’s coach, Don Haskins, did not choose his starting five because of their race but rather in spite of it. He simply wanted to win, and those five gave him the best opportunity to do so. His assistant, Moe Iba, confirmed this, saying, “The fact that he was doing something historic by playing five blacks, that probably never crossed Don’s mind. Hell, he’d have played five kids from Mars if they were his best five players.”

6Stewart Udall, Secretary Of The Interior

Udall, the Secretary of the Interior to both John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson in the 1960s, became involved in the civil rights movement through his intervention with a Washington Redskins football franchise that refused to integrate. The Redskins had been adamant in this refusal, with its team owner, George Marshall, once saying that the team would “start signing Negroes when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites.” Marshall’s position on the matter was assailed by many, with one columnist referring to him as “an anachronism, as out-of-date as the drop kick.” Despite the pleading of the press and fans, not until Udall stepped in and threatened retribution on the federal level did the Washington Redskins become the last team in the NFL to integrate. Since the Redskins’ new stadium was on federal land, Udall informed Marshall that if he continued to refuse to be integrated, the team would not be allowed to use it. In 1962, Marshall heeded Udall’s ultimatum, and the Redskins were finally integrated.

5Don Barksdale And His US Olympic Teammates

Barksdale was the first African American to represent the US on the Olympic basketball team, and his role in the civil rights movement was in a Kentucky arena in 1948, the year after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Barksdale’s moment was during an exhibition game when his teammates passed a water bottle down the bench, with each man taking a sip. After Barksdale took his, he passed it to a teammate—“Shorty” Carpenter of Arkansas—who drank from the bottle without hesitation. While this moment seems like nothing more than a minor detail today, the water bottle drew the attention of all those in attendance, many of whom felt that Carpenter could have made a statement by refusing to drink. This was especially true given that whites and blacks in the South rarely, if ever, drank from the same glass or from the same water fountain at the time. He didn’t refuse, and the game went on. Barksdale would later go on to become the first African-American All-Star in the NBA, playing for the Boston Celtics alongside Chuck Cooper.

4Kathrine Switzer & Roberta Gibb

Before 1967, no woman had officially run in the Boston Marathon, and the Boston Athletic Association (BAA) did not willingly issue bib numbers to women who applied. The Amateur Athletic Association (AAU) did not formally accept women as participants in distance running, fearing that their bodies could not handle the rigors of long distances. Roberta Gibb ran the Boston Marathon in three consecutive years (1966–1968) but did so without a bib number, having to hide in the bushes at the race’s starting line to avoid being spotted. Switzer, however, was issued a bib number but not with the full blessing of the BAA—according to the BAA, she did not clearly identify herself as a female entrant and signed her entry form as “K.V. Switzer.” She started the race unnoticed, but around the fourth mile, the press bus caught sight of her, causing a stir. Once race officials were notified, one of them even tried to rip off her bib number and physically remove her from the race before another runner—“Big” Tom Miller, a nationally ranked hammer thrower and former All-American football player—pushed him aside. Switzer officially finished the race and helped to clear the path for female participation in distance running events.

3Francois Pienaar & Nelson Mandela

Francois Pienaar grew up under apartheid in South Africa, when it was common to hear Nelson Mandela referred to as a terrorist who deserved to have been imprisoned for all of those years. As a rugby player, Pienaar was a part of the 1995 Rugby World Cup that came to symbolize the changing of South Africa, and Mandela supported the South African team and dismissed the notion that the springbok—the team’s emblem and a notorious symbol of apartheid—should be tossed aside. Instead, Mandela used the Rugby World Cup as an opportunity to unite the nation once again under the banner of sports. Upon South Africa’s victory, Mandela, who wore a South Africa rugby shirt that prominently featured the springbok, presented the cup to Pienaar, the white South African team captain. The image was an important one, as it came to be recognized as a moment of reconciliation for a formerly divided nation. Pienaar and Mandela became quite close thereafter, and the man known as Madiba ended up attending Pienaar’s wedding and becoming godfather to one of the Rugby captain’s children.

2Al Davis

Oakland Raiders owner Al Davis saw his football legacy somewhat tarnished during the last decade of his life, as the Raiders endured an extended period of futility that has continued to the present day. The team has not made the playoffs since its Super Bowl run of 2002, and many observers blame Davis for being out of touch with the game. Too many forget that Davis was an innovator of the highest order throughout the overwhelming majority of his life in football, and that included his attitude toward issues of civil rights. In 1963, just a year after the Washington Redskins had to be forced to integrate its team, Davis was refusing to play a preseason game in Mobile, Alabama as a protest against the state’s laws on segregation. Davis, again protesting the inherent unfairness of segregation, also implemented a policy stating that the Raiders would not play in cities in which players would have to stay in different hotels due to race. Davis was also responsible for hiring the second African-American head coach in the NFL in Art Shell and also the first female front-office executive in Amy Trask. Shell, a former offensive tackle with the Raiders, played under the league’s second Latino head coach, Tom Flores, who was also hired by Davis.

1Willie O’Ree

O’Ree didn’t even realize that he had broken the color barrier in the NHL in 1958, saying, “It just didn’t dawn on me. I was just concerned about playing hockey.” O’Ree grew up in Canada, playing both hockey and baseball, and as a teenager, he had the opportunity to meet Jackie Robinson in Brooklyn after being invited to camp with the Milwaukee Braves. The two spoke briefly, and after Robinson told him that there were no black kids playing hockey, O’Ree corrected him, saying, “Yeah, there’s a few.” Less than 10 years later, O’Ree would be making his NHL debut for the Boston Bruins. O’Ree had to endure taunts and insults while playing games on the road, but he was steadfast in his belief that those taunts deserved no response from him. There were even times when, while in the penalty box, O’Ree would be spit on and have objects thrown at him because of his race. O’Ree went on to work with the NHL after completing his professional hockey career, serving as the director of youth development for the NHL’s diversity program. J. Francis Wolfe is a freelance writer whose work can be seen daily at Dodgers Today. When he’s not writing, he is most likely waiting for “just one more wave” or quietly reading under a shady tree.