10SS City Of Chester

On the morning of August 22, 1888, in San Francisco Bay, the departing SS City of Chester collided with the incoming RMS Oceanic, a steamliner twice as large. As the Chester headed out of the bay to Eureka, California, carrying her 106 passengers and crew members, the fog was so dense that the crew of each ship missed seeing the other until they were only half a mile apart. Too late to avoid a crash, the Oceanic sheared the smaller vessel almost in two, propelling many of the Chester‘s passengers and crew into the swirling bay. Others were trapped on the ship by the rush of water. The damaged ship sank in just six minutes. Of the 16 fatalities, three were crew members and two were children. Local newspapers ran stories accusing the Oceanic‘s 74 Chinese crew members of ignoring cries from the Chester‘s white passengers as they drowned. In truth, the Oceanic crew had acted heroically, pulling as many victims as possible to safety. At least one crew member risked his own life by jumping into the turbulent water to rescue a child. The racist controversy was also fueled by the Oceanic carrying 1,062 Chinese steerage passengers. At that time, the Chinese Exclusion Act, signed into law by Chester A. Arthur, prohibited Chinese immigration because of the “Yellow Peril.” Americans feared an Asian menace, especially Chinese workers taking scarce California jobs away from white workers. Horace Greeley once summed up the racist sentiment of the time: “The Chinese are uncivilized, unclean, and filthy beyond all conception without any of the higher domestic or social relations; lustful and sensual in their dispositions; every female is a prostitute of the basest order.” Despite the unfair treatment, court records of the time document the heroics of the Chinese crewmen. The initial criticisms eventually changed to praise for the Oceanic‘s crew when the truth was revealed. In just a few years, the sunken ship was largely forgotten. The Chester was accidentally rediscovered by researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2014. Although they aren’t going to raise the ship, they are determined to tell the true story of the Oceanic crew’s bravery on that fateful day.

9Sao Jose-Paquete De Africa

Discovered just off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa, the Sao Jose-Paquete de Africa is the first known slave ship that sank with its human cargo of slaves aboard. Although researchers from the Slave Wrecks Project haven’t found human remains yet, they know the Sao Jose was a Portuguese slave ship because iron bars used as ballast were found in the wreckage. Back then, vessels undertaking long journeys used heavy weights to keep them stable. The weight of human cargo was too light and variable, especially if any slaves died. Ballast was used to compensate for the low weight of slaves. Setting sail from Mozambique in December 1794, the Sao Jose began its four-month journey to deliver 400–500 slaves to sugar plantation owners in Maranhao, Brazil. Pressed against one another, the slaves were shackled in the hold almost constantly during the trip. Twenty-four days into its voyage, the vessel ran into a severe storm as it came around the Cape of Good Hope. Trying to circumvent the violent winds, the Sao Jose sailed close to shore, where it quickly broke apart after hitting submerged rocks. The crew signaled for help by firing a cannon. The captain, crew, and about half of the slaves were saved. Although the captain tried to rescue the remaining 212 slaves, they died in the rough water. “The slave owners had a vested interest in people surviving,” said Stephen Lubkemann of George Washington University. “It’s like you have a barrel of apples, and you don’t want them to spoil. It’s a horrible analogy but that’s how the owners viewed them.” Within two days, the rescued slaves were resold.

8Huis De Kreuningen

In early 1677, the French tried to seize Tobago, a Dutch-controlled island in the southern Caribbean. That touched off a significant naval battle between the two powers, sinking as many as 14 ships. Including women, children, and African slaves, the total loss of life was about 2,000 people. No one had ever found evidence of the sunken ships until the summer of 2014. At that time, maritime archaeologist Kroum Batchvarov and a colleague discovered a cast-iron cannon at the bottom of Rockley Bay. In just 20 minutes, they spotted several cannons, some of which were 18-pounder guns. Although they didn’t find timbers from the ship, the divers did observe several Dutch smoking pipes, pottery jars, lead bullets, and Leiden bricks. They haven’t confirmed it yet, but their findings are consistent with the sunken Dutch warship Huis de Kreuningen. The only other Dutch ship large enough for these cannons wasn’t destroyed. “Although we have some written records of the battle itself, we possess no detailed plans of 17th-century warships,” Batchvarov says, “so our only sources of information about the ships of the day are the wrecks themselves. It isn’t overstatement to say that what has been discovered is a treasure trove for archaeological researchers.” At almost 40 meters (130 ft) long, the Huis de Kreuningen was the Dutch fleet’s largest ship. However, it was smaller than its French counterpart, the Glorieux. The Huis de Kreuningen was also outmanned and outgunned. Although the crew fought fiercely, their captain, Roemer Vlacq, was believed by some accounts to have set his ship on fire to avoid capture. Supposedly, the fire spread to the Glorieux and destroyed it. The details aren’t known and accounts vary, but we do know that the Dutch ultimately repelled the invasion and retained control of Tobago.

7HMS London

For 350 years, historians have debated what caused the famous English warship HMS London to blow up when it wasn’t in battle. Built in 1656, the London participated in the siege of Dunkirk a couple of years later. But she is most famous for returning the exiled King Charles II to England to restore his rule after Oliver Cromwell died in 1658. A mysterious explosion destroyed the ship in the Thames Estuary in 1665. Over 300 people died, including an unusually large number of women. Who were they? Wives? Lovers? “It’s a good question why there were so many women, and one on which I wouldn’t care to speculate,” said archaeologist Dan Pascoe. Only one woman and 24 men survived. On the day she blew up, the London was sailing from Chatham to Gravesend to pick up Sir John Lawson, her new commander, before embarking on any missions during the second Anglo-Dutch war. There were 300 barrels of gunpowder onboard. Historically, many people have believed that the ship met her end when gun crews were reloading cartridges with gunpowder. It’s unknown whether the men were preparing for a 21-gun salute. However, in 2014, an excavation team began to question that explanation for the explosion. Could recently recovered tallow candles or a clay pipe have provided the flames to spark the explosion? If the divers hope to find more information, they’ll need to work fast before the wooden ship disintegrates in its watery grave.

6The Champagne Schooner

In 2010, a stash of 168 bottles of 170-year-old French champagne, preserved in almost perfect condition, was found around the wreckage of a trade schooner in the Baltic Sea off of Finland. Although the local government took possession of the sparkling wine, scientists from the University of Reims snagged a small sample for testing. From images on the inside surface of each cork, the researchers were able to distinguish the brands. At least one, Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin, is still made today. That gave the scientists an excellent opportunity to compare today’s version of Veuve Clicquot to its 19th-century, Baltic Sea counterpart. The 19th-century version had more sugar and lower alcohol content. According to the researchers, this probably resulted from the colder climate back then as well as the type of yeast used. In addition, 19th-century vintners added 17–23 times more sugar to their champagne products than used today. Analysis of the older champagne also revealed higher levels of chlorine, copper, iron, and sodium. This was due to differences in the manufacturing process as well as the use of copper sulfate in vineyards to stop disease. We don’t have much direct information about the ship. However, by measuring sugar levels in the champagne, researchers believe they can determine where the schooner was headed. Russians liked the sweetest wine, often adding table sugar to make it even sweeter than originally produced. The French and Germans wanted about half as much sugar in their champagne as the Russians. Americans and the British liked the least sugar, about 7–20 percent of the Russian version. From the moderate sugar content of these bottles, scientists believe the ship was headed for the Germanic Confederation. Finally, a panel of experts tasted the champagne. At first, they used descriptions like “cheesy,” “animal notes,” and “wet hair.” But after swirling the wine in a glass to give it oxygen, their characterizations changed to “grilled, spicy, smoky, and leathery” with floral and fruity notes. Lead researcher Philippe Jeandet also tasted it. “It was incredible,” he said. “I have never tasted such a wine in my life. The aroma stayed in my mouth for three or four hours after tasting it.” Some of the bottles were auctioned for as much as €100,000 apiece. Enologists (specialists in blending wine) are now investigating whether deep-sea aging will enhance the flavor of certain wines.

5Nuestra Senora de Encarnacion

While searching for the ships of pirate Captain Henry Morgan in 2011, underwater archaeologists discovered the Nuestra Senora de Encarnacion, a Spanish merchant ship that sank off the coast of Panama during a storm in 1681. Next to a pirate ship, the Encarnacion is quite ordinary. But that’s exactly why the archaeologists are so excited by their find. The ship is remarkably well preserved, so it gives researchers an unexpected, firsthand look into late 17th-century shipbuilding and lifestyles. The Encarnacion was part of the Tierra Firme, the foundation of Spain’s trading economy. Each year, these ships would transport supplies to the colonists in the New World and return with precious metals, gemstones, and other items. In the wreckage, there were no gold coins or other sensational cargo. Instead, researchers found everyday items that could be used in multiple ways. “The sword blade could serve as a weapon of the Crown’s soldiers but could also be used for everyday cutting needs,” said project director Frederick Hanselmann. “The scissors that could assist in treating wounds would also have other uses in other professions. The mule shoes were necessary not only for transporting silver and gold across the isthmus but transporting goods and merchandise from one town to the next.” Researchers are also excited to learn how ships of this time were constructed. “Ships that were built hundreds of years ago didn’t come with blueprints,” explains Hanselmann. So far, they’ve learned that shipbuilders spread a thin coating of granel—cement made of lime, pebbles, and sand—to act as permanent ballast on these vessels. Granel could also be used to construct buildings in the New World.

4HMS Victory

Leading a fleet of warships in late 1744, the first-rate warship HMS Victory, commanded by the respected Admiral Sir John Balchen, rescued a Mediterranean convoy by driving away a blockade of French ships in Lisbon. The Victory protected the convoy until it reached Gibraltar. Then, while returning to England, the mighty flagship was lost with all hands in the English Channel during a violent storm. At least 1,000 men died. Controversy has dogged the vessel ever since. With as many as 100 bronze cannons, it was the world’s most powerful and technically advanced warship. (To be clear, this is the predecessor to the Victory famously commanded by Admiral Lord Nelson—they’re two different ships.) At first, the accusations flew about why and where it sank. Was rotting timber or the top-heavy design responsible? Had it veered off-course to the “graveyard of the English Channel,” perhaps smashing into the Casquets west of Alderney? Balchen was posthumously accused of poor navigation, while the lighthouse keeper at Alderney was court-martialed, supposedly for failing to burn the lights. Yet despite repeated attempts, no one could find the sunken ship. Then, in 2008, Odyssey Marine Exploration found the sunken ship in the English Channel. It was almost 100 kilometers (60 mi) west of the Casquets, so neither Balchen nor the lighthouse keeper was at fault. But a new controversy has erupted. The Victory is believed to have a 4-ton cargo of gold coins worth at least $160 million (and possibly $1 billion). The Maritime Heritage Foundation, a British charity chaired by Lord Lingfield, received title to the ship by British authorities. The Foundation then entered into a deal with Odyssey to excavate the site. For anything it recovers, Odyssey will receive 80 percent of the fair market value for commerce-related items, such as coins, and 50 percent for warship-related items, such as weapons. Critics are railing against the financial arrangement with Odyssey and against the company disturbing such an important war grave. Lord Lingfield has also been accused of profiting from the arrangement and exaggerating his family ties to Admiral Sir John Balchen. Lord Lingfield denies the allegations.

3M/V Wilhelm Gustloff

Even today, the sinking of the Nazi ocean liner the M/V Wilhelm Gustloff has the dubious honor of being the largest maritime disaster in history. Although there was no official passenger list, it’s believed that approximately 9,300 people died, and more than half were children. Originally a cruise ship for members of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, the Gustloff was converted first into a hospital ship and later into a floating barracks during World War II. By late 1944, with the Soviet Union’s Red Army advancing into East Prussia, German citizens made a concerted effort to flee the area, hoping to avoid Soviet retribution. Many German refugees rushed to Baltic ports, seeking ships that would help them escape. On January 30, 1945, one of those departing ships, the Gustloff, carried over 10,000 sailors, women, elderly men, and children from Gotenhafen. The vessel was designed for under 2,000 people. But the ship’s death sentence was truly signed by foolish decisions made by Nazi military personnel. First, only one small torpedo boat, instead of the usual convoy, sailed with the Gustloff to protect her. Next, the captain insisted on a speed of no more than 12 knots, rather than the preferred 15 knots that would have outrun any Soviet submarines. He didn’t want to overtax the engines because the ship hadn’t sailed for a few years. Then he headed into the open sea to avoid possible mines along the coast, which left the ship vulnerable to submarine attack. The unwise decision to light up the ship like it was on holiday ultimately revealed her position to Soviet submarine S-13, which successfully fired three torpedoes into the Gustloff. Supposedly, a radio message had been sent to the Gustloff, warning that a convoy of German minesweepers was heading her way. To avoid collision, the captain made the fatal error of switching on the ship’s bright lights. There were no minesweepers, but there were later rumors of a plot to sabotage the ship with a fake message. If true, it worked.

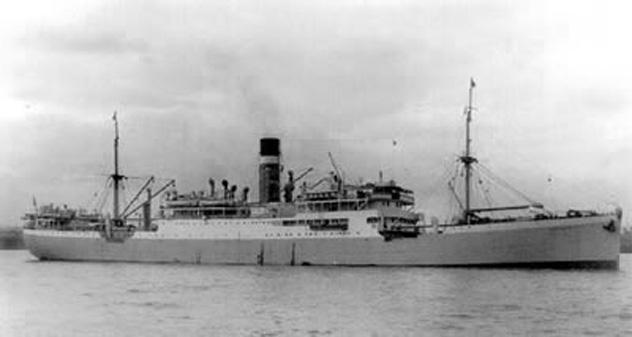

2SS City Of Cairo

During the Battle of the Atlantic in World War II, the British Merchant Navy ship SS City of Cairo was torpedoed twice and sunk by a German U-boat 770 kilometers (480 mi) south of the island of St. Helena. The Cairo had been en route to England from Bombay after London called in £34 million ($50 million) in silver rupees to help pay for the war. Including 150 passengers, there were 311 people aboard the ship. On November 6, 1942, a German U-boat fired a torpedo into the Cairo, forcing all aboard to scramble into six overcrowded lifeboats. Six people died during the evacuation. After 10 minutes, U-68 sank the Cairo with a second torpedo. The U-boat surfaced, coming close enough to the lifeboats for its captain, Karl-Friedrich Merten, to give the survivors directions to the closest shore. Then he bid them farewell. “Goodnight,” he said. “Sorry for sinking you.” The lifeboats became separated in the South Atlantic, with an additional 104 lives lost before the ordeal was over. According to some accounts, on November 19, a British ship rescued 155 survivors in three lifeboats heading toward St. Helena. Another British ship picked up all but the remaining two survivors. In December 1942, the last two survivors were rescued by the German ship Rhakotis. Unfortunately, one of them died when an Allied ship torpedoed and sank the Rhakotis. In 2011, a British salvage team located the Cairo, eventually recovering most of her cargo of silver rupees. The divers also found the propeller of the second torpedo, which had sunk the ship and ultimately led to the loss of 110 lives. When they were finished with the excavation, the salvage team placed a plaque on the underwater wreckage to honor the dead. It said simply: “We came here with respect.”

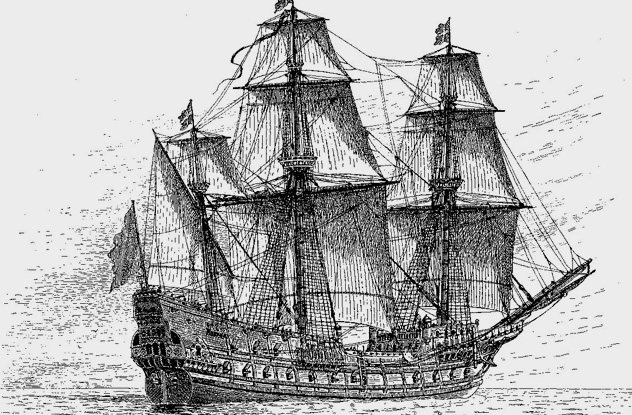

1The Mars

Named for the Roman god of war, the Swedish warship Mars was the biggest, most powerful vessel in the world in the 1500s. Although both archaeologists and treasure hunters had searched for the sunken vessel for years, it wasn’t found until 2011. Before then, the legend of a ghost rising from the ship’s watery grave to protect it from discovery appeared to be true. Archaeologists consider the remarkably well-preserved vessel—one of the first large, three-masted warships ever built—to be the missing link in their knowledge of early ships. Until now, they’ve known almost nothing about 16th-century warships. For its time, the Mars had unmatched firepower, filled with guns, cannons, and eight kinds of beer for her men. It was a war machine whose own cannons brought her down. If you believe legend, a king’s hubris is to blame. Erik XIV, who had the Mars built, felt threatened by the Catholic Church’s power. So, in an effort to reduce the strength of the Church, the arrogant monarch seized church bells, melting them to build cannons for Sweden’s new warships, including the Mars. According to legend, the Mars was a cursed ship because of these sacrilegious cannons. On May 31, 1564, the Mars sank off the coast of Oland, a Swedish island in the Baltic Sea, while fighting Danish forces that had allied with German soldiers. Although the Swedes were initially successful against the Danes, the Germans came back to throw fireballs at the Mars. They got close enough to board the ship. With flames engulfing them, both sides continued battle onboard the Mars. The intense heat triggered explosions of the ship’s cannons, eventually sinking the once-powerful vessel. As many as 900 sailors from both sides were lost, along with the ship’s treasure of gold and silver coins. “It’s not just a ship, it’s a battlefield,” said maritime archaeologist Johan Ronnby. “[Diving on the wreck], you’re very close to this dramatic fire onboard, people killing each other, everything was burning and exploding.” When divers surfaced with a piece of the ship’s timber, they could still smell a charred odor emanating from the burned wood.