10The Five Suns

The Aztecs absorbed many nearby civilizations, so their creation myth—the Legend of the Five Suns—came in different versions and adaptations, but the central tenets stayed the same. The gods tried five times to create the human world, each time with a different god becoming a sun. Four times, the world was destroyed. The fifth sun survived and sustained the present Earth. In one account, the gods convened in darkness to create that fifth sun. It could only be powered by a god jumping into a bonfire. Two gods volunteered for the honor: strong Tecuciztecatl and old Nanahuatzin. They believed Nanahuatzin was too old to make a good sun, so the younger god was chosen. However, when Tecuciztecatl came near the bonfire, he cowered. Nanahuatzin bravely walked in and was consumed, becoming the Sun. Ashamed, young Tecuciztecatl leaped in after and became the inferior moon. The moral: Through the sacrifice of the gods, modern humans came to be. And the Aztecs did not forget this debt owed.

9The Aztlan Exodus

The Nahua peoples—disparate tribes that spoke a common language—once populated Central America. According to legend, they emerged from a place of seven caves and settled in a territory known as Aztlan. Descriptions of Aztlan differ. Some tribes called it a utopia, but the Aztec tribe saw it as a place of servitude to cruel masters. Under the leadership of the Aztec hero Huitzilopochtli, the people fled south. Now free, they cast aside their tribal name, which meant “people from Aztlan,” and called themselves “the Mexica” instead. Later historians would term them the “Aztecs” once more. By the time the Mexica arrived, other Nahua tribes had already taken all the good land and had become warring city-states. The Mexica persuaded the local king, Culhuacan, to let them squat on his land. The portion of land given wasn’t arable or all that good. Nonetheless, the Mexica served as mercenaries in the Culhuacan army to earn their keep.

8The Flayed Princess

The Mexica absorbed the culture of their patron city-state, becoming a more civilized, religious, and technologically adept people. They served admirably in battle, earning the king of Culhuacan’s appreciation. When the Mexica invited the king’s daughter to serve as their queen and become the wife of Huitzilopochtli (who was long dead and now deified), the king agreed. But little did he know that the Mexica would perform the divine marriage the best way they knew how—by sacrificing her. When the king went to a banquet in his daughter’s honor, he was horrified to find a ceremonial dancer wearing her skin. This sent him into a rage, and he waged war against the Mexica, who wondered what they had done wrong. Driven out of their land, and with nowhere to go, they were forced into the nearby lake of Texcoco. There was little but the marshy islet of Tenochtitlan on which to settle. Things were not all bleak for the Mexica, though. On the islet, they saw an eagle nest on a nopal cactus and took it as a sign from their god that it was their destiny to live there. And they endeavored to make the best of it.

7The Artificial Island

The first thing the Mexica did to their islet was turn it into an island. They reclaimed land from the marshes by building drainage canals, but this would not be enough to sustain their planned city. They needed farmland that simply wasn’t available. What they did next was quite ingenious. They built floating gardens known as chinampas. They staked out rectangles the length of skinny football fields in shallow riverbeds. They enclosed them with walls of wattle—a material that is a mishmash of clay, tied reeds, and animal dung. The farmers then built up the riverbed of the fenced-off area with sediment, mud, and dead vegetation until it was up to the level of the water’s surface. Next, they weaved a web of floating sticks and then piled reeds and mud from the river bottom over that, creating arable land. The seeds that grew from crops spread to adjacent boats and were rowed over to the next chinampa. Chinampas yielded up to seven crops a year, much more than you could get on dry land at the time.

6Tezozomoc’s Stone Fist

The new Mexica city couldn’t fend off all the warring city-states alone. They agreed to pay tribute to Tezozomoc, the king of the nearby Tepanec Empire. They also worked as mercenaries in his army. Tezozomoc was a strict ruler who demanded heavy taxes from his subjects. One Mexica ruler devised a strategy to reduce the tax hit by marrying one of Tezozomoc’s many daughters. Not only did the idea work, but Tezozomoc became fond of the Mexica and married more of his daughters to Mexica nobles. Tezozomoc became like a stern stepfather to the Mexica. He gave them the state of Texcoco as a tribute. While under his protection, the Mexican ruler was finally recognized as a king by the other Nahua tribes. Meanwhile, the island of Tenochtitlan physically grew. Marshlands filled with soil. Huts made of cane and reed turned to houses of stone. Aqueducts were built, as well as more chinampas and canals, turning the island city into something of a New World Venice. Larger temples were built over the original smaller ones, becoming the world-famous step-pyramids.

5Maxtla The Usurper

When the king of the Mexica died, Tezozomoc appointed his favored grandson Chimalpopoca to the throne. His grandson was young, though, so Tezozomoc appointed himself regent until Chimalpopoca matured. When Chimalpopoca came of age, however, Tezozomoc thought him too incompetent to rule. He continued to reign as regent for the next 60 years. Tezozomoc was over 100 years old when he died. His oldest son Maxtla thought himself the rightful heir to the Tepanec Empire, but the council of elders elected his brother to the throne. Maxtla answered by killing the brother. Not only that, he killed anyone who opposed his claim. Chimalpopoca sided with Maxtla’s brother. Not long after Maxtla took power, Chimalpopoca was assassinated.

4The Battle Against Maxtla

The Mexica couldn’t take their revenge on Maxtla without help. They needed allies. Not long before, Prince Nezahualcoyotl had been the nephew of the king of Texcoco, a conquered servant of the Tepanec Empire. The Tepanecs had killed the king and sent Prince Nezahualcoyotl into exile, keeping him from becoming king and avoiding his potentially rebellious rule. Amid the chaos of Maxtla’s betrayal, Nezahualcoyotl returned to reclaim his throne. The Mexica saw that the new Texcocon king was just as eager to avenge his uncle as they were to avenge Chimalpopoca. They allied. And they together convinced a third nation to join their cause. What historians would later call the Triple Alliance—the founders of the Aztec Empire—was born. When Nahua tribes fought, they sought to maim, not kill. The did this because they needed captives for human sacrifices or to sell as slaves. But when the Triple Alliance attacked the Tepanec capital, they took no prisoners. Bodies littered the streets. Maxtla and his troops, stunned by this brutal tactic, fled to the palace. Maxtla, according to one account, was discovered in the steam baths. Prince Nezahualcoyotl killed him with his own hands, avenging his uncle. The Triple Alliance burned the Tepanec capital to the ground. Together, they took over, expanding their territory. The Mexica took the lead, gradually becoming the dominant force in the alliance and the head of the Aztec Empire.

3The Puppet Master

Tlacaelel was a man who served many Aztec kings as a guiding hand. He was the architect of the Triple Alliance, created to avenge his brother Chimalpopoca and to serve his brother Moctezuma, the new emperor. Tlacaelel was instrumental in creating laws to unify the Empire and its people, but he also had a dark side. If he and his brother thought a conquered nation capable of causing trouble, they would kill or exile their king, replacing him with a puppet who was compliant with Aztec rule. Tlacaelel ordered the books of the conquered nations to be burned. He ordered the books of his own nation burned. He rewrote history, erasing the Mexica’s nomadic roots and recasting them as a chosen people. Huitzilopochtli, the folk hero who’d led them out of Aztlan, was now to be considered a central god and the embodiment of the Sun itself, unable to be sustained without continual human sacrifice. When the realm became more peaceful, he introduced what would be known as the “Flower Wars.” These were mutually prearranged wars for the sole purpose of collecting prisoners for human sacrifice.

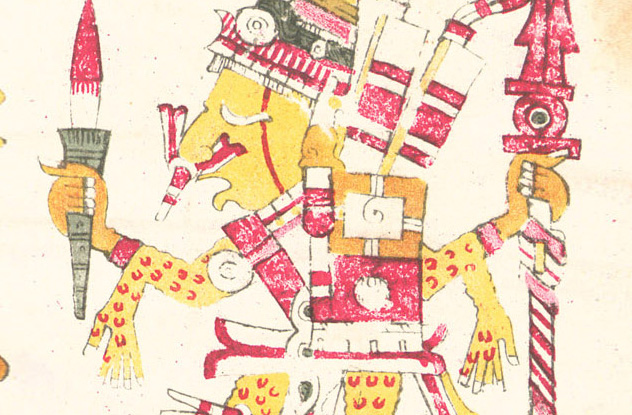

2Jaguar And Eagle Knights

Aztec society was stratified—royals, priests, nobles, commoners, and slaves. When lower-ranked peoples are suppressed, they tend to rebel. But the Aztec rulers placated commoners with a path to nobility to strive for, to become an Eagle or Jaguar Warrior. It was akin to the European concept of knighthood, whereby one advanced in rank by performing great deeds. For the Aztecs, these deeds were specific—capturing enemies in battle and bringing them to the temples for ritualistic sacrifice. If a common warrior captured 20 souls, he was promoted to Jaguar or Eagle knighthood. This meant he had become a nobleman, permitted to dine at the royal palace and drink alcohol. He could also take concubines. But in truth, these warriors were mostly composed of nobles. Any commoners who rose to such heights were exceptions. Jaguar and Eagle knights dressed the part in battle. The Jaguar warriors wore the skin of the spotted cat, while the Eagle Knights donned feathers. They fought with a sword-like club spiked with obsidian—volcanic glass. They also used slings, spears, and daggers, but the aim of battle was rarely to kill. Their goal was to provide more fuel for the sacrifices.

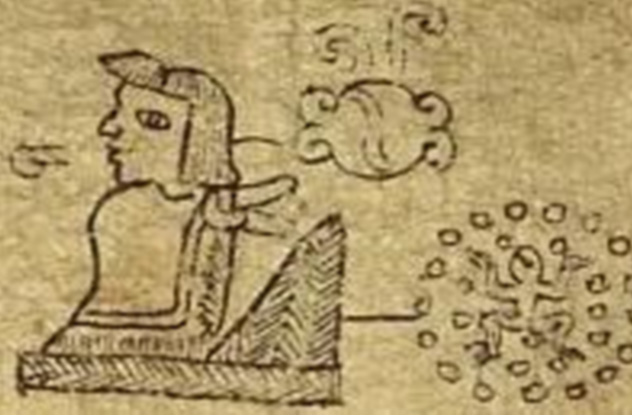

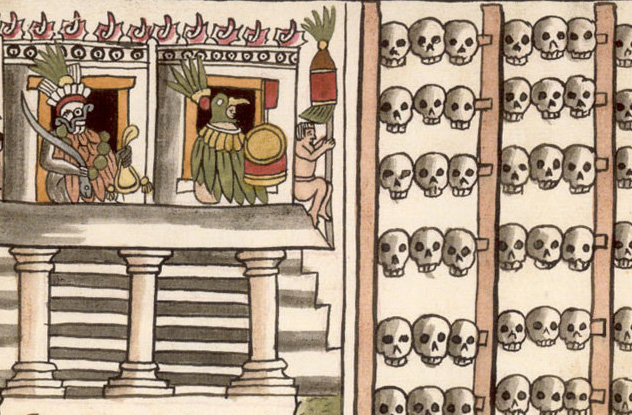

1Human Sacrifices

The Aztecs lived on what they believed to be a 52-year cycle. Every day, the Sun waged a cosmic war against the Moon and stars. If the Sun did not receive enough nourishment in the form of sacrificial offerings, it would not rise at the end of its cycle, dooming the world to darkness. The Aztecs also believed that human hearts were fragments of the Sun, which is why they would slice open the chest of a sacrificial victim and hold his still-beating heart up to the sky. This freed the fragment to rejoin the Sun. It was not just the Sun to which Aztecs sacrificed. To the rain god Tlaloc, they sacrificed young children. As priests led the little ones up a mountain path to immolation, they encouraged them to cry. Tears meant plentiful rain in the coming season, making for good crops. Sometimes, priests would summon the spirit of a god to inhabit the body of a mortal. The Aztecs would then treat this person as the actual embodiment of the god—giving him offerings and worshiping him—until a year later, when they sacrificed him. The gods regularly sacrificed themselves for the mortals, just as the mortals bled for the gods.

+More Sacrifices

When young Aztec warriors returned with their captives, the prisoners of war were sacrificed in ritualistic combat. The prisoner was chained and handicapped while four Jaguar Knights took him on one at a time. If he survived, the knights would then attack him all at once. If still he survived, he was then brought to a priest for a more traditional sacrifice. One such captive, who turned around and fought alongside the Aztecs in a time of need, was offered his freedom and a trip home. However, he refused, demanding to be sacrificed to the gods. Many of the Nahua saw it as a privilege to be sacrificed to serve the community. At the end of the 52-year cycle, the Aztecs would extinguish all the flames at night. If the Sun rose in the morning, it meant the sacrifices over the previous cycle were sufficient to nourish the gods. A man was then sacrificed, his chest opened, and a flame lit inside his carcass. From the flame, the Aztecs would reignite all the lights in the village, in some ways similar to the modern passing of the Olympic Torch. Matt is a freelance editor and writer. He’d like you to read a bit of his Korean historical novel about a former slave girl’s rise to power.