Yes. Yes, it is. And yet there have been secret organizations that created the world as we know it.

10The Carbonari

After Napoleon’s defeat in 1814, the European powers had to decide what to do with the territory that he’d ruled as part of the First French Empire. The borders of Europe were redrawn at the Congress of Vienna, mainly decided by Great Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Napoleon had conquered Italy in 1805, and when the Congress signed their Final Act in June 1815, Italy had been nicely carved up. Austria got a chunk of the north, while the rest was splintered into a number of small states. The Carbonari formed during the decade of turmoil, but their exact origins are unclear—the society took the “secret” part quite seriously. They may have been imported from France. They could have been a homegrown offshoot of freemasonry; they had initiation ceremonies, symbols, and hierarchies similar to that famous secret group. The Carbonari, with as many as 60,000 members, was by far the largest of several secret societies on the Italian peninsula at the time. Though they didn’t form with the goal of unifying Italy, they were responsible for setting everything in motion. The largest pre-unification state was the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which comprised Sicily and Naples. It was ruled by King Ferdinand, who operated mainly as an Austrian pawn. In 1820, the Carbonari led a revolution that forced Ferdinand to give up power and create a constitution for the country. Austria ultimately marched into Naples and tore the constitution up because they wanted their man in charge. However, this act of rebellion created the widespread movement for Italians to rise up and unify, a movement that succeeded in 1861.

9La Trinitaria

The Dominican Republic owes its existence as a country to a secret society known as La Trinitaria, or The Trinity, founded in July 1838. The island of Hispaniola had been under Haitian rule since 1822. The Spanish-speaking westerners weren’t entirely keen on being ruled by the French-speaking Haitians on the east of the island. The desire for independence found its leader in Juan Pablo Duarte, sometimes called the father of the Dominican Republic. Duarte, along with eight comrades, founded La Trinitaria at age 25. The organization aimed to educate people and spread nationalist sentiment. Duarte wrote an oath for members of the group, under which members declared they would “swear and promise, by my honor and my conscience, in the hands of our President, Juan Pablo Duarte, to cooperate with my person, life and goods in the definitive separation from the Haitian government and to plant a free, sovereign and independent republic, free from all foreign domination, that will be called the Dominican Republic.” The group did all they could to hide their existence from authorities. Duarte created a cryptic alphabet for secret communication. Members used pseudonyms and operated in small cells of just three people. The group also worked with rebels in the east who hoped to overthrow the government for their own reasons. In 1843, they attempted a revolution—and it failed. Several Trinitarians were jailed, and Duarte fled to Venezuela. Yet the group had done their work well, and a second uprising the following year led to Dominican independence being declared on February 27, 1844. Duarte returned to become president, but he faced a military coup before he could take office. Duarte was exiled from the country he’d created. He died overseas in 1864.

8Afrikaner Broederbond

The Afrikaner Broederbond, founded in 1918 and open only to white men over the age of 25, sought complete control of South Africa—culturally, economically, and politically. The group kept their secrets well, and we don’t know a lot about them. During the 1930s, they promoted Afrikaner nationalism. They gained so much influence over the Reunited National Party that the prime minister called the party “nothing more than the secret Afrikaner Broederbond operating in public.” By 1947, they were in control of the South African Bureau of Racial Affairs. It was there that members devised apartheid, probably the most infamous example of segregation of the last 60 years. Their rise to power was so dramatic that it led one writer in 1978 to say, “The South African government today is the Broederbond and the Broederbond is the government.” The membership roster included 143 military officers and every prime minster and president of the country from 1948 until Nelson Mandela’s election in 1994. Since the 1990s, the group has been forced to rebrand and now calls itself the Afrikanerbond. They even have a website. They now officially accept any adult regardless of color, gender, or religion, and they claim to seek only a better life for all African citizens.

7Filiki Etaireia

The Filiki Etaireia (“Friendly Brotherhood”) had goals that belied their innocuous name. They started the Greek revolutionary war of 1821, which lasted 11 years and led to the formation of the modern-day Greek nation. In 1814, Nikalaos Skoufas and Athanasios Tsakalov, a couple of merchants, put together a plan for a secret organization to overthrow Ottoman rule in Greece. Their group would have four levels of membership, and there would be a supreme authority. Everyone would have secret identities. The merchants based their plans closely on the structure of the Freemasons, as they were themselves members. They made the organization as elaborate as possible and chose a name. Then they realized that they’d get more done with actual members. In two years, they only managed to recruit around 30 people. Their most enthusiastic member was Nikolaos Galatis, who claimed to be a relative of Ioannis Kapodistrias, Greece’s ambassador to the Russian Empire, perhaps the Ottomans’ biggest rivals. The rebels, seeing an opportunity for a powerful ally, sent Galatis to recruit his alleged relative. Kapodistrias’s response was unenthusiastic. He told Galatis, “The only advice I can give you is not to speak to anyone else about this and to return immediately to the place you came from; and tell those who sent you that if they wish to avoid destroying themselves—and dragging down with them the whole of their innocent and unfortunate race—they must renounce their revolutionary activities.” Galatis did the opposite and began talking about the Etaireia to anyone who would listen. He told the Russian police. He even told the Czar. Kapodistrias had a nervous breakdown. Galatis eventually left Moscow under Russian surveillance and kept trying to recruit people. In the end, the Friendly Brotherhood themselves had him murdered because he simply refused to grasp the “secret” part of their society. By 1819, the society had managed to set up a more competent recruitment drive and expanded to six membership levels. People who joined by taking the oath were given more information based the contributions they made. Illiterate, unskilled workers (“brothers”) were on the bottom of the ladder. Moving higher up required ever more elaborate rituals and donations, as well as learning a bunch of secret signs, but came with new titles: “Referenced One,” “Priest,” and (at the top) “Shepherd.” The organization leaders knew they couldn’t maintain their conspiracy forever and sought a leader to start a rebellion. They turned to Kapodistrias again, but he refused, once again saying their plan was foolhardy and would never work. They ended up asking a Russian officer named Alexander Ypsilantis, who agreed. They announced the Greek Revolution in the Spring of 1821, and though the society itself broke down as war broke out, Greece won its independence. The very first head of state of independent Greece, often considered to be the founding father of the modern country, was Ioannis Kapodistrias. Because who says a man can’t change his mind?

6The Germanenorden

The 20th-century German secret society that called itself the Germanenorden believed firmly in the superiority of the Aryan race, and in 1916 they adopted the Swastika as their symbol. They were also extremely anti-Semitic. You can probably see where this is going. The group formed in 1812 to combat perceived Jewish and Freemason conspiracies by beating them at their own game. They had elaborate initiation rituals which included people dressed as knights, kings, bards, and even forest nymphs. Members were required to prove their Aryan ancestry with several generations’ worth of birth certificates. In 1918, the group morphed into the Thule Society, under the rule of Rudolf von Sebottendorff. Their underground activities in 1919 helped defeat communism, and they morphed further into the German Workers Party. In 1920, they were taken over by Adolf Hitler, who got rid of the occult traditions he found distasteful but kept pretty much everything else.

5The Black Hand

The Serbian organization Unification Or Death, better known as the Black Hand, formed on May 9, 1911 with the goal of fighting Ottoman rule. Within a few years they numbered around 2,500 members, led by Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijevic, known as “Apis” after the Ancient Egyptian bull deity. Members took an oath that placed the secrecy of the group above their own lives, stating “before God, on my honor and my life, that I will execute all missions and commands without question. I swear before God, on my honor and on my life, that I will take all the secrets of this organization into my grave with me.” The group operated in cells. At the bottom of the ladder were groups of three to five people. Each bottom-level cell knew only details for their immediate contact but nothing of other cells or of the group’s higher leaders. The idea was that if members didn’t know anything, they couldn’t give anything away. In 1914, Apis came up with a plan to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The mission was successful—and it triggered a war more deadly than any that had come before it.

4Katipunan

Katipunan is a shortened version of Kataastaasan Kagalang-galang Na Katipunan Nang Manga Anak Nang Bayan, which means “Supreme Worshipful Association of the Sons of the People.” The organization formed in the Philippines in 1892 to oppose Spanish rule. The founders were all freemasons, and the rituals, coded passwords, and male-only membership criteria were inherited from that tradition. The Katipunan added an extra element, however—they signed everything in their own blood, starting with their founding document on July 7, 1892. Today, original copies of oath letters declaring “I have signed this document in my own blood that runs through my veins” sell on eBay for a couple hundred dollars. The society managed to gain tens of thousands of members while keeping their existence entirely unknown to the ruling Spaniards. However, in 1896, a worker at a printing factory producing Katipunan documents confided in his sister. They were overheard by a nun, who told a priest, who told the Spanish authorities. The printing shop was raided, and the secret was out. On March 22 of the following year, members decided to abandon secrecy altogether. They’d managed to organize enough people under the Spaniards’ noses to start all-out rebellion. The Philippine Revolutionary Army defeated the Spanish and declared independence on June 12, 1898. The Spanish denied the new state and told the United States that the Philippines were all theirs. The US, having won its independence from imperialist colonizers through a revolutionary war, apparently thought no one else should get the chance to do the same. They moved troops into the Philippines and ruled for 50 years. Nevertheless, June 12 is still celebrated today as Philippine Independence Day.

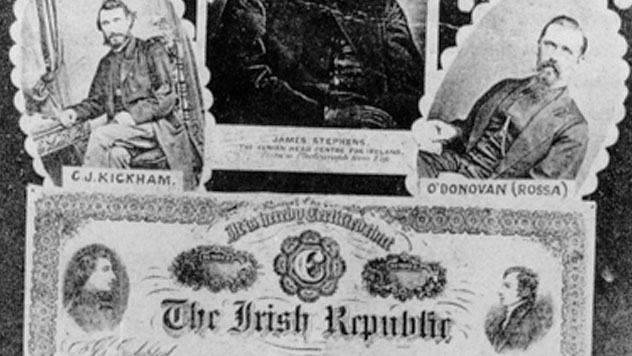

3Irish Republican Brotherhood

Members of the 19th-century international Irish independence movement were called Fenians, and the branch in Ireland itself was founded by James Stephens. Following a failed uprising in 1848, Stephens fled to Paris where he befriended fellow fugitive John O’Mahony. While in France, both men got swept up in Louis-Napoleon’s 1851 coup d’etat, and ended up in at least one secret society modeled after the Masons. Stephens wrote that he studied “Continental secret societies, and in particular those which had ramifications in Italy,” a reference to the Carbonari. O’Mahony traveled to New York and founded the US-based Fenian Brotherhood. Stephens returned to Ireland in January 1856, most likely driven not by revolutionary fervor but by the fact that his life in Paris had become one of poverty. In December 1857, Stephens received correspondence from O’Mahony promising financial assistance to set up a militant organization in Ireland. On St Patrick’s Day in 1858, Stephens received 80 pounds. He and a group of others swore an oath in his lodgings that night, founding the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, later renamed the Republican Brotherhood. The Fenians had outposts all over the world—England, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia within the British Empire; the US and South America beyond it. They operated in groups called circles. At the center of each was a colonel, who recruited nine captains. Nine sergeants were recruited by each captain, and nine privates by each sergeant. Each man knew only his direct superior. In 1910, leadership of the IRB went to Thomas Clarke, who increased membership particularly among young Irishmen. In May 1915, he set up a seven-man military council, which arranged the Easter Rising of 1916. The leaders of that rebellion were forced to surrender. Many blamed the organization’s secrecy for the failure because it had made it difficult to arrange the rebellion. Nevertheless, the group continued to be a powerful faction for the next few years, leading into the Anglo-Irish war that eventually saw the Irish Free State created in 1921.

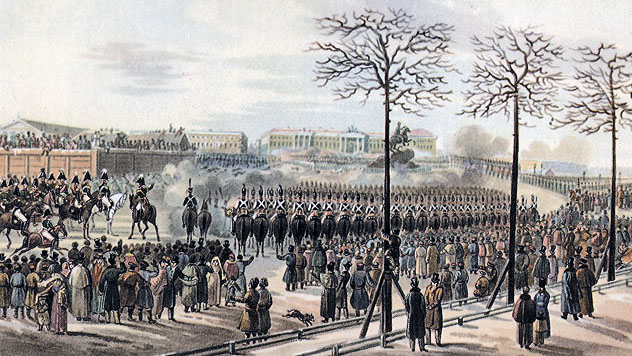

2The Union Of Salvation

The Russian Empire fell in 1917, but the seeds of revolution were sown almost 100 years earlier. The Decembrist Uprising in 1825 saw 3,000 rebel troops try to capture the Winter Palace and usurp Czar Nicholas I on his first day in power. The rebellion was put down, but it changed Russia. Nicholas set up a spy network to monitor the population and censored the press and education. Regional autonomy was abolished for places such as Poland. The Decembrist Revolt was organized by the Union of Salvation. The organization had humble beginnings: Its six founding members—military officers and friends—gathered in private homes until one among the group suggested they should set up a secret political organization. The society’s aims were vague, though all members had problems with the political and social status quo. Members pledged to oppose idle nobility, blind faith in authorities, and the abuses of the police and courts. In 1817, they drafted a constitution that formalized initiation rituals and four ranks of membership. Only the top two tiers—the founding “Boyars” and the long-serving “Elders”—knew the society’s true goals. New members on probation were called “Brethren” and pledged to support the Society even if they didn’t know to what end. Prospective members were called “Friends” and stayed around to see if membership should be granted. The society ended up rebranding as the Union of Welfare and taking on a more philanthropic and public role. In 1821, member Pavel Pestel’s radicalism unsettled much of the leadership, and the group splintered into northern and southern factions, with Pestel taking charge of the latter. He used the group’s influence to organize a plan for a rebellion when the Czar died to prevent his heir from taking power. Unfortunately, Pestel’s influence wasn’t as great as it needed to be for the haphazard, directionless revolution to succeed in anything—other than inspiring the Czar to make Russia even less free.

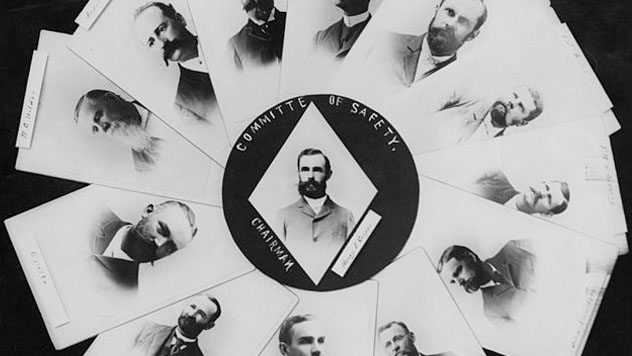

1The Hawaiian League

The Kingdom of Hawaii formed at the start of the 19th century but lasted less than 100 years before it became part of the US. Its downfall was plotted by an organization known as the Hawaiian League, made up of 200 wealthy Americans and Europeans unhappy with King Kalakaua. They believed the king was too extravagant and, perhaps more importantly, diluted their own power on the Islands. The secret society formed around a constitution written by Lorrin A. Thurston at the start of 1887. No copies survive. Within a year, the group grew to 405 members, but they disagreed on their goals. Some wanted to annex to the US, while some wanted to form an independent republic. Yet they certainly all wanted to overthrow the monarch. A paramilitary group known as the Honolulu Rifles became the league’s most important ally. In 1893, they overthrew Queen Liliuokalani, who’d risen to the throne two years earlier. For a few years, Hawaii was a republic, but the revolution ultimately led to it becoming a US territory in 1898 and the 50th state in 1959. If you’re a member of a secret society, Alan would love to hear about it on Twitter.