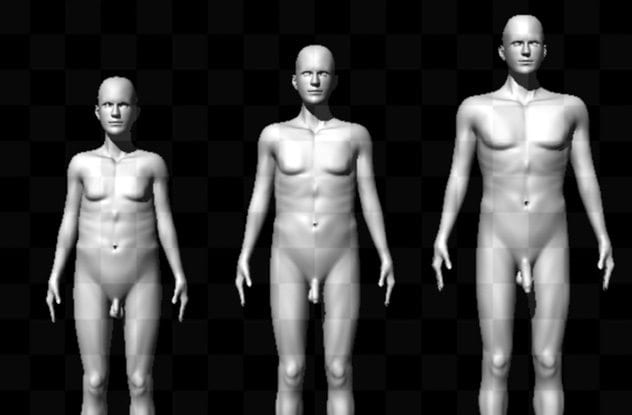

10Prehistoric Women Increased Penis Size Through Sexual Selection

A joint study by several Australian biologists and zoologists concluded something that most of us already suspected—penis size really does matter to women. The study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences asserted that women generally found men with larger penises more attractive, but overall attractiveness increased based on a combination of factors such as height and body type, and no individual trait determined male attractiveness. More interestingly, the study also made several observations regarding the reason why human penises evolved to be “larger than necessary.” This might be a consequence of prehistoric women using penis size as criteria for sexual selection. Evolutionary biologists claim this was possible due to genitalia’s conspicuity. Primitive humans had an upright posture and protruding genitals that made the penis quite obvious, even when flaccid. Females regularly choosing endowed males for mating would have led to an increase in penis size over the course of human history.

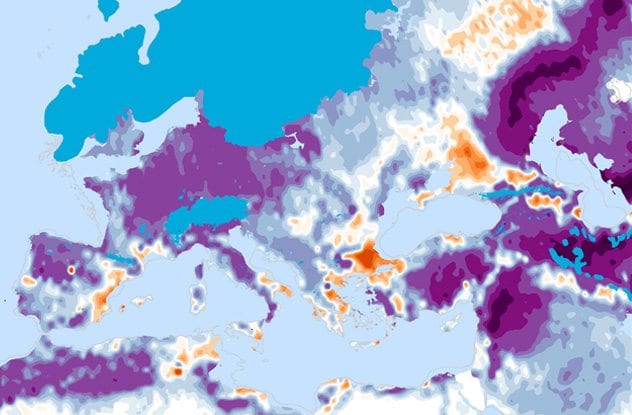

9Ice Age Humans Shaped European Landscapes

An international research team at Leiden University has found that Europe experienced a massive deforestation event during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) over 20,000 years ago. Moreover, they assert that the cause was mobile groups of Upper Paleolithic humans who burned entire forests down to create clearings more suitable for habitation. Semi-open landscapes made it easier for humans to move, forage, and hunt. European forests were already vulnerable during the LGM due to cold climate and low CO2 levels. Wildfires not only increased their mortality levels but significantly reduced their ability to regenerate. Approximately 30 percent of forest cover was lost permanently.

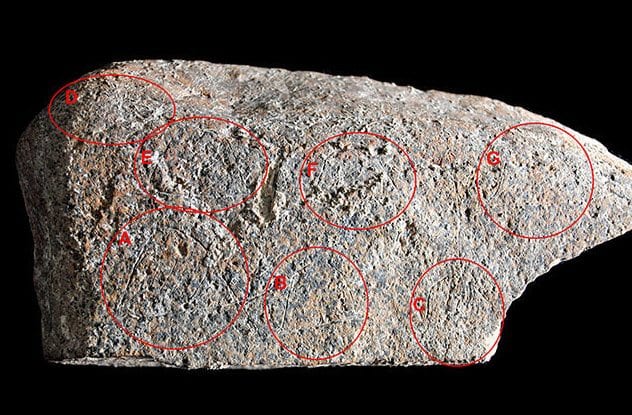

8Stone Age Artists Were Avant-Garde

A discovery made late last year at a dig site near Barcelona is thought to represent the earliest known depiction of a human settlement. At almost 14,000 years of age, the carving would predate the previous record holder by almost 6,000 years. While not everyone is convinced, the archaeologists who discovered the etching argue that it represents seven huts—the first artistic impression of human society. The anonymous artist has drawn comparison to Picasso because he broke the artistic conventions of the day and painted something other than the abstract animal and human depictions that dominated Stone Age art. There is plenty of evidence that a hunter-gatherer village once inhabited the area around the time of the carving. Critics argue that the etchings may, in fact, represent unique, stylized animals. While this counters the idea of depicting a human settlement, it still shows that Paleolithic Picasso rejected artistic norms and came up with his own style.

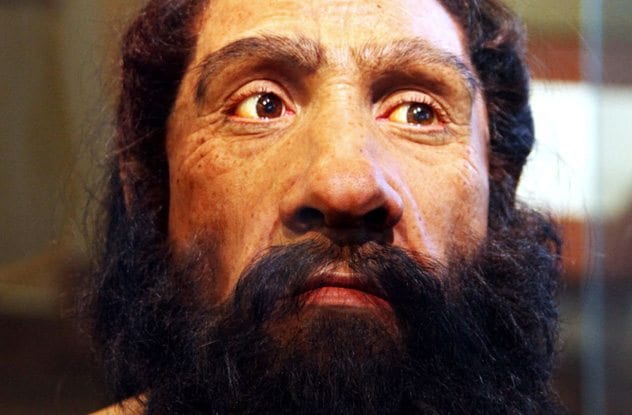

7Prehistoric Ancestors Were Resistant To Smoke

The use of fire is, undoubtedly, a landmark moment in the evolution of man, but experts are still debating when exactly it originated. According to current thinking, it could have happened anytime from 350,000 to 2 million years ago. In an attempt to provide an answer, scientists at Leiden University studied our genetic footprint, looking for possible markers related to fire use. Particularly, they were interested in the adaptations of humans to deal with the toxic compounds of smoke and whether they were also present in prehistoric hominins or not. Surprisingly, the research team discovered that our ancient ancestors were better suited for handling the toxins than us. Both Neanderthals and Denisovans had these gene variants, as do modern chimps and gorillas.

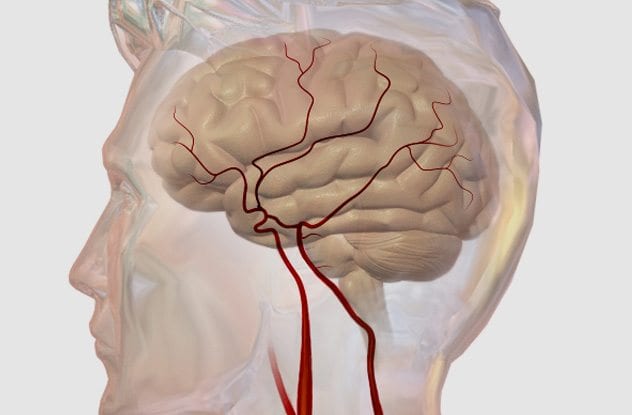

6Bloodthirsty Brains Made Us Smart

Intelligence is the defining characteristic of humans, and we have been studying the evolution of the human brain for decades. A joint project between researchers from Australia and South Africa challenges the commonly held belief that the increase in human intelligence is simply correlated to an increase in brain size. They argue that an increase in blood supply to the brain is the dominant factor. According to the study, brain size has increased by 350 percent over the course of human evolution, but blood flow to the brain increased by 600 percent. As the brain became more active, its metabolic needs increased, and meeting the new requirements was crucial for the brain’s continued evolution. To that end, arteries traveling to the brain became increasingly larger. By studying the artery holes in skull fossils, scientists were able to get a good idea of the evolution of blood flow, which lined up nicely with our understanding of the evolution of human intelligence.

5World’s First Farmers

A study by Harvard Medical School published earlier this year in Nature aimed to uncover the first people in the world who turned to farming 12,000–8,000 years ago. Their results pointed at three distinct groups in the Near East: a previously reported group in the Anatolian region of Turkey and two newly described ones in the Levant and Iran. This represented the first large-scale genome analyzes of prehistoric people from the Near East. The region’s warm climate exposed bones to degradation and microbe contamination, making it difficult to obtain high-quality DNA samples. Scientists overcame this obstacle through a new technique called in-solution hybridization, as well as using genetic material from ear bones, which preserved the integrity of the DNA better than other bones. The study also alludes to the existence of a hypothetical ancient population called Basal Eurasians, one of the first peoples to live outside of Africa. All Near East groups appear to share their ancestry.

4Neanderthal Inbreeding Made Us Less Fertile

When modern humans first left Africa for new homelands, they ran into Neanderthals. The two groups started interbreeding, which is why, even today, non-Africans have approximately 2 percent Neanderthal DNA. One study published by the Genetics Society of America revealed that when both groups were still active, that number was closer to 10 percent. Due to inbreeding, Neanderthals were much less reproductively fit than Homo sapiens. That mutation was passed on to modern humans, along with a host of other harmful genes. Most of those mutations were eliminated from our DNA within generations, but the infertility gene has stuck around. The study estimates that, historically, non-Africans would have been 1 percent less likely to reproduce thanks to their Neanderthal heritage.

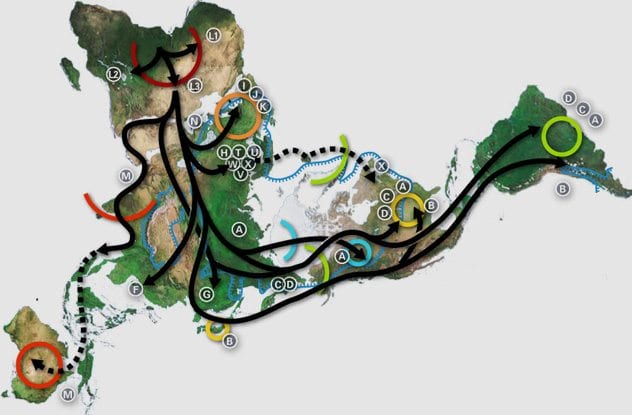

3Face Mites Evolved Alongside Us

All humans have face mites. However, until recently, we never thought to explore the natural history of these tiny parasites. One landmark study conducted by the California Academy of Sciences looked at mitochondrial DNA belonging to Demodex folliculorum and revealed that their evolution is closely linked to that of humans. 70 samples gathered from all over the world showed that face mites have different genetic lineages based on geography. Mites from Africa are different compared to mites from Asia despite being the same species. Not only that, but the study also shows face mites are not casually transmitted from one person to another, and they persist for generations even if you move to a faraway region. So far, the divergence of mites closely mirrors that of early humans migrating out of Africa. The study will continue for several years in hopes that the evolution of mites will provide us more information about the evolutionary history of humans.

2One Single Migration Is Responsible For All Non-Africans

Earlier this year, Harvard Medical School published a study that examined hundreds of new genomes from all over the world to better understand the dynamics between ancient populations. They also presented evidence asserting that all non-Africans are descended from a single migration out of Africa occurring between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago. The project analyzed the genomes of approximately 300 people from populations all over the globe. The results were corroborated by two other research groups conducting their own independent genome studies in Estonia and Denmark. While the study mostly falls in line with the already accepted “Out of Africa” migration theory, it does disprove the idea that indigenous people from Australia and New Guinea were descended from an earlier migration. Scientists are hopeful the genome project will yield many more revelations, calling the current results “just the tip of the iceberg.”

1Solving The World’s Oldest Mystery Death

Lucy the Australopithecus is the most famous fossil in the world. Ever since her discovery in 1974, she has provided us with invaluable information about our prehistoric ancestors. One mystery involving Lucy has evaded us, though—how did she die? Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin believe they have the answer. Lucy died after falling from a tall tree. That’s the conclusion anthropologists reached after carefully studying all the recovered bones using High-Resolution X-ray Computed Tomography. A compressive fracture in the right humerus was unlike typical fossil damage but resembled an injury commonly encountered when breaking a fall. Similar, but smaller compressive fractures on other bones were all consistent with trauma from a fall. If proven true, this theory could also solve another long-standing debate regarding Australopithecus afarensis involving whether they moved through trees or not.

![]()