But that is a very modern view of fossils. They have been unearthed by humans throughout history and weren’t easily understood by those with no idea of the true age of the Earth. Without a scientific explanation, people assigned folkloric significance to the strange rocks they dug up. Here are ten of the weirder pieces of fossil folklore.

10 Toadstones

Sweet are the uses of adversity, Which, like the toad, ugly and venomous, Wears yet a precious jewel in his head. –“As You Like It” by William Shakespeare Strange, shiny, round stones can be found throughout the world. These little rocks have been used as gems, despite their rather drab brown color. Called Bufonite, these stones derive their name from the Latin bufo, meaning “toad.” These toadstones were alleged to be the gems which toads have in their skulls. In so-called sympathetic magic, like cures like. Since toads are toxic, it was thought that toadstones could protect against poison. The problem is that toads do not have stones lodged in their heads. In fact, toadstones are the round teeth of a genus of ancient fish called Lepidotes. People who believed they were being poisoned might swallow a toadstone to get its full power. But since toadstones were so valuable, they would be reluctant to let it go to waste. It could be dug out from the chamber pot, hopefully washed, and used again.

9 Thunderbolts

Belemnites are an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods. All that is usually left of these soft-bodied animals is the hard, cylindrical rostrum, an internal structure that gave their body shape. These bullet-shaped remains litter fossil beds worldwide. Given their unusual shape, belemnite fossils have attracted a number of fanciful explanations. Were they elf candles? St. Peter’s fingers? The most widespread belief about belemnites is that they are the earthly remains of lightning strikes. Called thunderbolts, thunderstones, and thunder-arrows, they were thought to have protective powers against lightning. In parts of the Netherlands, belemnites were placed on the roofs of houses to stave off strikes before the invention of the more effective lightning rod.

8 Angel Money

Nummulites are the fossilized remains of large, single-celled protozoans. In shape, they resemble small coins or lentils. When the Greek writer Strabo visited the pyramids, he was shown nummulites and told that they were the remains of food given to the slaves who built the monuments. The pyramids are constructed of limestone that is full of nummulites, and as the stone has weathered, the fossils have fallen out, to be found by credulous visitors. The myths associated with nummulites depend heavily on the form they take in the local area. Where they take the shape of coins, they were known as angel money, St. Peter’s money, or Ladislaus’s pennies. The name “nummulite” derives from the Latin nummulus, meaning “little coin.”

7 Snake Eggs

Sea urchins are still alive today and can be found in seas worldwide as well as in kitchens and restaurants. How is it, then, that fossilized sea urchins were misidentified in the past? Echinoderms, the group to which sea urchins belong, are covered with spines. Usually after death, they fall off, leaving a ball with a five-pointed star on it. Various uses have been made of urchin fossils, everything from ensuring that bread rises to wards against lightning. But perhaps the oldest piece of folklore which survives was first hinted at by Pliny the Elder. He referred to fossil urchins as ovum anguinum—“snake eggs.” In the British Isles, these snake eggs were thought to be produced from froth made by mating snakes. If you could steal this ball from the snakes without letting it touch the ground and then flee the angry serpents across a body of water, you would have a powerful magical item against poisoning.

6 Tongue Stones

Sharks have skeletons of cartilage and do not leave large fossil remains. What they do leave behind are teeth. Some of these ancient sharks, like the massive Megalodon, left teeth of an almost unbelievable size. Megalodon and other large sharks’ teeth were about the size and shape of a tongue. Thus they became known as glossopetrae, or “tongue stones.” The magic of these tongue stones was proof against poison of all sorts. Dipped into a drink, they would neutralize anything sprinkled in by an assassin. Should a snake bite you, the stone had only to be pressed against the bite. Tongue stones were thought to generate within rocks and even breed. The offshoots at the side of some shark teeth were seen as young tongue stones budding from a parent. Tongue stones had a starring role in the birth of paleontology. Working in Italy in 1666, Nicolaus Steno dissected an enormous shark caught by fishermen. He was struck by the similarity between the shark’s teeth and tongue stones. This made him realize that the tongue stones may have been the teeth of once-living sharks.

5 Vishnu’s Chakras

Ammonites are perhaps one of the most easily recognized fossils. The spiral shell of an animal much like a nautilus, their distinctive shape makes them a favorite of fossil collectors. In India, however, some ammonites are items of religious veneration, and the most valuable examples hide their spiral shape. Saligrama (or “Shaligrams”) are ammonites found in the bed of the Gandaki River. What makes these ammonites special is that they are thought to resemble the Sudarshana Chakra, the spiky disc weapon that the god Vishnu is often shown with. The best shaligrams are those with only the edge of the fossil showing from the sphere of the stone. Shaligrams can be found in many Hindu temples and can be used to remove sins. Touching them is an act of prayer, and washing in water that has had shaligrams in it can wash sins away.

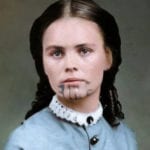

4 St. Hilda’s Snakes

Whitby in Northern England is riddled with ammonites. The fossils are so common there that they can even be found on the town’s coat of arms. Once again, the shape of the fossils has generated a local myth. In Whitby in the seventh century, St. Hilda wished to build an abbey to provide a place to worship God. Unfortunately, the area in which she wished to build was home to thousands and thousands of adders. In a miraculous turn of events, St. Hilda killed the snakes by throwing them from a cliff, her wrath turning them to stone. Thus, in Whitby, ammonite fossils were known as snakestones. Locals weren’t above cashing in on this legend by carving a snake’s head onto the end of an ammonite fossil and selling it to visitors in need of a trinket.

3 Devil’s Footprints

The study of folklore can be hugely rewarding for scientists. Herbs and plants used for centuries can yield powerful new drugs. In Italy, a series of footprints known to locals as Ciampate del Diavolo—“the Devil’s Footprints”—turned out to be something even more interesting than the name would suggest. Around 385,000 to 325,000 years ago, an active volcano spewed up ash. Much later, locals stumbled on tracks left in the ancient ash. Since they knew how hot volcanoes are, they assumed that only a devil from Hell could have walked in it. In 2003, paleontologists examined the tracks and declared them to be the oldest-known footprints left by a human species.

2 Dinosaur Footprints

Dinosaur footprints have been marveled at for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. What exactly was believed to have left these footprints was dependent on the cultural folklore of the beholder. In ancient Greece, they were the footprints of heroes like Herakles. To Native Americans, they were the tracks of giant, legendary birds. In China, dinosaur trails were linked to the myths of dragons as well as more mundane animals. According to one study in China, there were four main strands of folklore attached to dinosaur footprints. Where the footprints were left by three-toed therapods, they were interpreted as being those of golden and heavenly chickens. The heavier tread of herbivorous dinosaurs was seen as those of a rhino. Others saw dinosaur tracks as plant leaves. Still more saw them as footprints of the gods. Whereas dinosaur bones taken from the rocks may disappear or be lost, dinosaur tracks in the bedrock may last for generations, reinforcing local myths.

1 Griffins

The mythical griffin is a creature with the body and tail of a lion but the head and wings of an eagle. Such an animal is clearly impossible, but you might reconsider that idea if you did a little digging in the Gobi Desert. There in the sands can be found the remains of a dinosaur called Protoceratops, a smaller relative of Triceratops. With its beaked jaws and diminutive crest, the skull of a Protoceratops resembles nothing so much as an enormous eagle. It has been argued by some that with this skull and the four legged body, Protoceratops was the model of the Griffin. A detached skull could also be combined with other bones to create a new beast.