10 The Yellow Fever Epidemic Of 1795–1805

Yellow fever is a tropical disease caused by a virus spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Occasionally, it shows up in higher latitudes. One devastating appearance in Philadelphia in 1793 soon spread to New York City and the entire Eastern seaboard. Though no one at the time understood what caused the disease or how it was spread, the initial reaction to quarantine boats coming from Philadelphia delayed the epidemic for a while. But by the summer of 1795, Manhattan began reporting its first cases of yellow fever. It was a grim disease. Victims experienced headaches, severe exhaustion, and slowed heart rates. Then came delirium, and patients’ skin and pupils would take on the yellow hue that characterized the infection. A copious amount of blood and black bile was vomited before the victims finally died. Officials were not alarmed at first. New York had brushes with yellow fever before that, which were easily contained. When bodies began to pile up, they denied that there was an epidemic, fearing a mass panic and exodus from the city and the attendant collapse of business. Part of the terror was not knowing the cause of the infection. Noah Webster sought to prove that the eruption of Mt. Etna in Sicily was to blame. Others speculated that rotting coffee in the docks was the culprit. Some doctors came close to the truth when they realized that the disease was not spread from person to person but from something in the “constitution of the air.” Consequently, the Health Committee ordered the cleanup of New York’s most notorious cesspools, sewers, swampy grounds, and crowded buildings, especially the “streets, yards, cellars and markets” near the East River. It also went after merchants who kept putrefying meat in their cellars. The fever did not abate. Bellevue Hospital was swamped with new cases throughout August and September. Poet-turned-doctor Elihu Hubbard-Smith noted in his diary: “Wherever you go, the Fever is the invariable and unceasing topic of conversation . . . People collect in groups to talk it over, and to frighten each other into fever, or flight.” He estimated that those who chose the latter course as numbering between 12,000–15,000. Smith opted to stay behind to attend to the victims and study the epidemic. He would pay with his life when the fever finally caught him in 1798. The approach of winter brought respite, but the first year left 730 New Yorkers dead. The fever returned with a vengeance 1798, 1803, and 1805. Claims of homemade cures abounded. “Lime-water mixed with an equal quantity of new milk” was said to be effective against the black vomit. Newspapers touted alkaline medicines; lime was reported as disinfecting the air from “poisonous vapor.” Totally ignorant as to the nature of the contagion, doctors treated it as they did scurvy, with “neutral mixtures, lemonade, cider, peaches, pears and apples.” 1,524 people died in 1798, or 4 percent of New York’s population. Before the worst was over, another 868 would succumb. Perhaps no other testimony would capture the horror better than a letter from a lady named Alice Cogswell, which said: What sad havoc does this pestilential fever make with the inhabitants of this world, wives torn from their husbands, husbands torn from their wives, and in some instances whole families swept to eternity without one left to mourn their loss. It is enough to make one’s heart weep drops of blood, or rather streams, my soul turns with horror from this scene of wretchedness and misery to the world beyond the grave where there is no more sorrow or grief. It is the god of heaven that thus desolates the world and he has just reason for it . . .

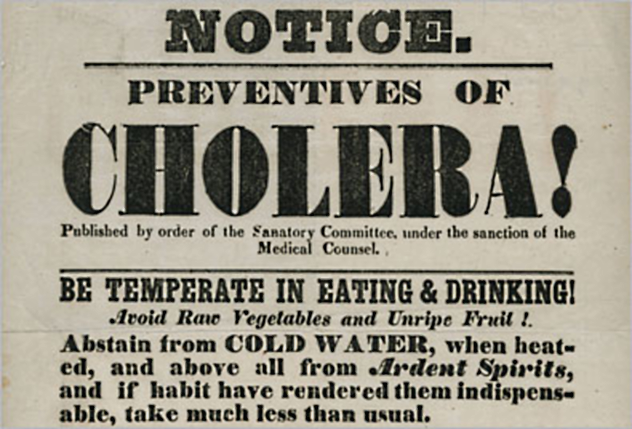

9 The 1832 Cholera Pandemic

The bacteria known as Vibrio cholerae, once endemic only to the Ganges River region, went global in the 19th century. European expansion along with better methods of transportation helped spread the disease. In the mid-1820s, it took to the old trade routes and penetrated the Far East, Afghanistan, and Russia from India. Western Europe watched apprehensively as the contagion made its way into the continent. By April 1832, cholera was in Paris. Americans hoped that the Atlantic would be a barrier as the plague ravaged Britain. But in June, the dread disease appeared in New York City, probably brought by immigrants arriving from Europe. The usual quarantines and clean-ups were ordered, but deaths increased during the summer months. However, unlike prior outbreaks where individuals were largely left to fend for themselves, the city government played a major role in fighting cholera. A special medical council was created, and response teams were on the alert. $25,000 was appropriated for special “cholera hospitals.” Unfortunately, ignorance of the germ theory of disease hampered efforts. Many still believed that cholera was a visitation of God’s wrath (and thus afflicted only sinners) or that it was a “poor man’s disease” (and thus ravaged only the less fortunate such as the Irish and African-Americans, who crowded the decaying slums of Five Points). But when the reality on the ground proved these ideas wrong, consternation and panic ensued. Victims suffered horribly. Stomach cramps, nausea, fever, and diarrhea made their heads and limbs cold. Cardiac failure due to electrolytic imbalances caused death within a few hours after the first symptoms. Unlike yellow fever, cholera could be transmitted through soiled bedding, clothing, or infected water. The 80,000 people who fled New York (out of a population of 250,000) inadvertently spread the contagion to the surrounding areas. A witness remembered, “Our bustling city now wears a most gloomy and desolate aspect—one may take a walk up and down Broadway and scarce meet a soul.” Conventional medical remedies included bleeding, ingestion of calomel (a mercury compound), magnesia, camphor, morphine and opium, and enemas of chicken tea. More bizarre treatments included tobacco smoke enemas and electric shock therapy. Other patients had to endure beeswax or oilcloth plugs stuffed into their rectum to halt the diarrhea. By mid-July, there were about 100 deaths a day. But by Christmas, the disease had disappeared as suddenly as it had arrived, and no one knows why even today. Perhaps it was the change in weather, the dispersal of the fleeing populace, or the quarantine measures. New York suffered 3,515 deaths. In today’s city of eight million, that would be the equivalent of 100,000 deaths. The social and medical impact of the pandemic was substantial. Public wells were replaced by the Croton Aqueduct, which brought in clean water from upstate. Improved sanitation, advancements in public health, and information sharing among doctors are among the things that we owe to the grim events of 1832.

8 The Great Fire Of 1835

By the 1830s, New York had become the premier US city for business and trade thanks to the opening of the Erie Canal. Unfortunately, the fire department, so necessary to protect the city’s multiplying commercial buildings, was sorely undermanned. To make matters worse, New York had no reliable water supply. On December 16, 1835, the freezing firefighters were totally exhausted from putting out large fires two days before, and the water cisterns were empty. High winds buffeted downtown Manhattan. New York was unprepared for the coming disaster. The blaze began in a large warehouse at around 9:00 PM. Within 20 minutes, the wind had fanned it to 50 neighboring commercial buildings. By 10:00 PM, the fire had gobbled up 40 dry goods stores, and the damage already totaled millions of dollars. The struggling firefighters, hampered by the high winds, broke the ice on the East River to secure water, but the water froze in their hoses. Flammable material exploded and leveled buildings. Embers fell on Brooklyn and started another series of blazes there. Even ships on the piers caught fire. Volunteer firemen from Philadelphia joined in. Marines and sailors controlled the confused and panicking crowd. In the early morning hours, the inferno reached Wall Street and engulfed the magnificent Merchant Exchange, consuming its supposedly fireproof marble. Merchants desperately tried to evacuate their precious goods, only to have it fall into the hands of looters. Four hundred looters would eventually be arrested. With firefighters virtually helpless, there was no choice but to blow up buildings and private property along the path of the fire to deprive it of fuel. With Alexander Hamilton’s son James lighting the fuse, the buildings were demolished at about 5:00 AM, and the fire was under control soon after. To those surveying the devastation, it seemed like the city might not recover. The financial heart of New York––and of the whole nation—was in ruins. Seven hundred buildings, mostly business establishments, were in ashes, at a cost of $20 million. Thousands of New Yorkers were out of work. The stock exchange remained closed for four days. Fortunately, only two people were killed in the conflagration. Nicholas Biddle, president of the Bank of the United States, offered to help with reconstruction. A complete overhaul made the fire department a more efficient response team. The Croton Aqueduct assured the city of a reliable supply of water. New Yorkers took advantage of the destruction to revise the urban grid and widen the streets, greatly transforming the city.

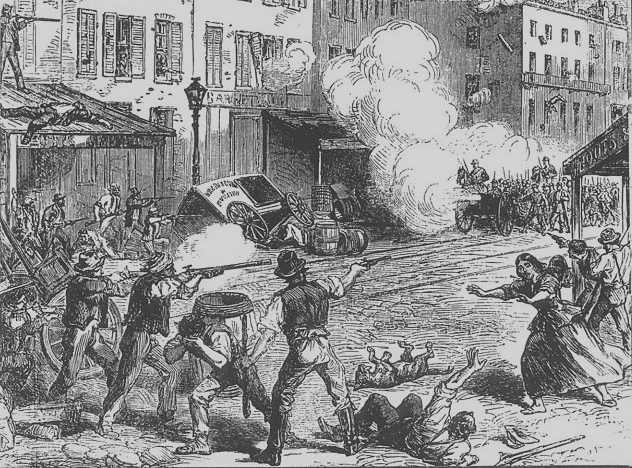

7 The Draft Riots

During the Civil War, New York was a city divided. Rich against poor, white immigrants against black, pro-war against anti-war, the seething cauldron of tensions kept America’s largest city on edge. Mayor Fernando Wood had even called for the city to secede from the Union. Only a spark was needed to ignite the powder keg. That spark was the military draft called in March 1863. Democratic politicians questioned its legality and said that it favored the wealthy (who could pay $300 for exemption) and blacks (who were exempt because they were non-citizens) while placing the burden on the poor. On the morning of July 13, the third day of the draft, a group of firefighters joined an angry crowd before the provost marshal’s office, protesting the conscription of the fire chief. The angry mob began to smash windows and invaded the office, forcing the officials to flee. The mob fanned out, targeting the offices of the pro-war press, especially Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. Homes of Republican leaders and the wealthy were attacked. Brooks Brothers, contractors of uniforms for the US Army, saw its store looted and destroyed. The rioters, mostly Irish, turned their savagery against the African-Americans whom they saw as competitors for jobs. They attacked and razed a colored orphan asylum, beating and killing a little girl who failed to flee. They lynched innocent blacks, mutilated their bodies, and sacked their homes. Two warships bombarded lower Manhattan to prevent the mob from taking over Wall Street and the Treasury. What was so remarkable about the draft riots was that they didn’t seem to be spontaneous outbursts but rather an organized rebellion—the largest civilian insurrection in US history. A definite strategy can be discerned—the effort to cut the approaches to the city, sever telegraph communications, seize the forts and armories, and divest the banks and Federal treasury vaults of cash. As the chaos spiraled out of control, the authorities debated how to restore order. New York’s Democratic governor, Horatio Seymour, an opponent of the draft, hesitated to deal with the mob. In an inflammatory speech, he cried: “Remember this! The bloody, treasonable and revolutionary doctrine of public necessity can be proclaimed by a mob as well as by a government!” Republican mayor George Opdyke took it upon himself to request federal troops. The soldiers, fresh from the battle at Gettysburg, marched on New York. Ten thousand troops relieved the battered police and took over the fight. Insurrectionists were mowed down by grape and canister and forced to retreat by the bayonet. Building-to-building firefights flushed out snipers. By 12:00 AM on July 16, the draft riots were over. Estimates put the dead from 100–1,000. Nobody really knows how many were killed in fires, drowned in the river, or secretly buried by friends or family. Hundreds of buildings were damaged. Blacks fled the city, and the African-American population of New York went down by 20 percent.

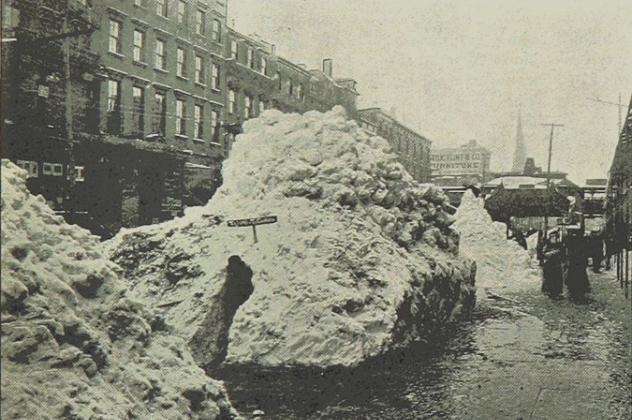

6 The Great Blizzard Of 1888

Temperatures were mild, and a light rain began to fall on March 11, 1888. New York had no inkling of the nightmare to come. Cold Arctic air suddenly collided with air from the Gulf of Mexico, causing temperatures to nosedive and turn the rain into snow. Hurricane-force winds were whipped up, reaching 137 kilometers per hour (85 mph) by midnight. New Yorkers awoke in the morning to find themselves buried in an ocean of white, reaching up to the second story of some buildings. For the people who braved the blizzard to go to work, it was frozen Hell. Elevated trains were stuck in snow, stranding 15,000 people. Those who chose to walk risked collapsing in the snow drifts and dying, as did Senator Roscoe Conkling, New York’s Republican leader. The winds tossed humans and horse cars aside. Telegraph and phone lines were knocked down. Damaged overhead electrical wires started fires that resulted in $25 million in damages. Water mains and gas lines, located above ground, froze. The city ground to a halt, like “a burning candle upon which nature had clapped a snuffer,” in the words of the New York Sun. Hotel lobbies were packed with stranded people seeking shelter. At Madison Square Garden, P.T. Barnum provided entertainment for the refugees. Some businessmen exploited the misery, raising coal prices from 10 cents a pail to $1. But many others rushed to help, like bakeries which stayed open through the night, distributing bread to the hungry. “The Great White Hurricane,” as it came to be called, killed 200 New Yorkers. The cityscape was changed once more when authorities learned their lesson and decided to put the city’s vital infrastructure—telephone lines, water mains, and gas lines—underground. More importantly, the famed subway system was conceived, enabling people to move about in spite of nature’s fury aboveground.

5 The 1896 Heat WaveThe Forgotten Disaster

Believe it or not, heat kills more Americans than floods, hurricanes, and tornadoes combined. Yet, heat waves don’t often make the headlines. They are “silent disasters,” leaving structures intact but exacting a terrible death toll. The specter of a hot day simply doesn’t scare most people. This explains why the heat wave that ravaged the East Coast and New York in 1896, “the deadliest urban heat disaster in American history” according to historian Edward Kohn, is now largely forgotten. For 10 days in August, temperatures hovered over the 30-degrees-Celsius (90°F) mark. There was no wind to give respite from the high humidity. In the crowded, squalid tenements of the Lower East Side, poor immigrant families baked alive in virtual ovens of 50 degrees Celsius (120 °F). Their men continued to labor 60 hours a week under the blazing Sun that was “still unwearied of scourging,” as the New York Times put it. Many succumbed to heatstroke. Searing asphalt pavements killed horses by the hundreds, and their rotting carcasses posed the danger of an epidemic. Newspapers underreported the severity of the situation, and City Hall did nothing. Because of a ban on sleeping in public parks, people sought relief by sleeping on rooftops or fire escapes. Many of the dead were adults and children who rolled off the roofs and fell. In the Lower East Side, some who slept on the piers similarly rolled off, fell into the water, and drowned. The high and mighty also felt the effects of the heat wave. William Jennings Bryan, Democratic front-runner for the presidency, saw his campaign in New York fizzle out when unforgiving temperatures forced people to desert Madison Square Garden, where Bryan formally accepted his party’s nomination. In an era when the government largely ignored the poor, Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt took on the responsibility of distributing free ice to the public. This was no small thing, as this life-saving luxury was beyond reach of poor families even in normal times, the cost being dictated by an “Ice Trust.” Roosevelt, five years away from the presidency, busted the ice trust and got in touch personally with the poor, shaping his future administration and the Progressive era of social reform. Temperatures finally went down on August 14. Thirteen hundred New Yorkers, mostly poor immigrant laborers, were dead. At least one lesson was learned: When the heat wave of 1919 struck, the city was ready with “ice stations” for the poor, which would evolve into the modern cooling center.

4 The Burning Of The SS General Slocum

Excited children and their mothers boarded the General Slocum on the bright Wednesday morning of June 15, 1904. The sidewheel passenger ship, the “largest and most splendid excursion steamer in New York,” would take the families from Kleindeutschland (Little Germany, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side) to their annual picnic on Locust Grove, Long Island. At about 10:00 AM, the General Slocum began its two-hour journey up the East River, with 1,350 passengers and crew on board, 300 of them children under age 10. Sometime later, a barrel of packing hay belowdecks caught fire, probably from a carelessly thrown match or cigarette. Crewmen tried to put out the blaze, but the ship’s antiquated fire hoses burst, despite a fire inspector’s approval of the equipment a month before. Captain William Van Schaick steamed full speed ahead for the pier at 134th Street, but the wind whipped up and fanned the flames. The festive mood onboard turned to panic. Mothers screamed for their children. Many jumped overboard and drowned, including a woman who actually gave birth during the chaos. Her newborn perished with her. Rotten life jackets proved useless. It was “a spectacle of horror beyond words to express—a great vessel all in flames, sweeping forward in the sunlight, within sight of the crowded city, while her helpless, screaming hundreds were roasted alive or swallowed up in waves.” Finding it impossible to dock at 134th Street, Van Schaick made a run for North Brother Island a mile away, intending to beach the Slocum. Boats followed, picking up a few survivors but mostly encountering the bobbing corpses of dead children. Rescuers on North Brother, including the nurses and staff of nearby Riverside Hospital, prepared to meet the ship on the shore. They dived into the water to pull out survivors as soon as the Slocum grounded sideways 8 meters (25 ft) from the shore. New York’s deadliest single-day disaster before 9/11 claimed 1,021 lives, mostly women and children. Many men of Little Germany came home from work that day widowers and childless. Utterly desolated, Kleindeutschland disappeared from the map of New York. The shattered families move further north, and some returned to Germany. The disaster also affected to a lesser extent the Italian and Jewish communities who had loved ones aboard the ship.

3 The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Manhattan, had a history of burning down their establishments after business hours to collect on the insurance. The Triangle, on the top three floors of the Asch Building, was a firetrap. Only one of the four elevators was functional and was accessible only from a narrow corridor. Two doors led to the street. One was locked from the outside to prevent employee theft, and the other opened inward. The fire escape was so narrow that it couldn’t accommodate all of the workers at one time. To make matters worse, Blanck and Harris refused to install sprinklers in case they needed to burn the factory—in reality a sweatshop—down. The coming tragedy was accidental, but Blanck and Harris were as guilty as if they had started the fire themselves. On that fateful Saturday, March 25, 1911, 600 workers were on duty at the factory on the ninth floor. Nearly all were immigrant teenage girls, toiling over sewing machines for 12 hours a day for a measly $15 a week in cramped conditions. The fire started in a rag bin on the eighth floor, and efforts to put it out with rotting and rusting equipment were futile. As the flames reached the floor above, the panicking girls jammed the elevator. Many plunged down the shaft to their deaths. Escape was foiled by the locked door, and those who reached it were burned alive. The fire escape, unable to bear the weight of the terrified workers, collapsed and crashed 30 meters (100 ft) to the ground. As horrified onlookers watched, desperate workers threw themselves out the windows to a fatal rendezvous with the pavement below. Within 18 minutes, 145 people were killed, the worst industrial disaster in New York history. They instantly became martyrs to the cause of industrial reform. Although a grand jury failed to indict Blanck and Harris on manslaughter charges, the government did take action in response to the public outrage. The Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law passed in October, and in the next three years, 36 state laws were put in effect regulating fire safety and workplace conditions.

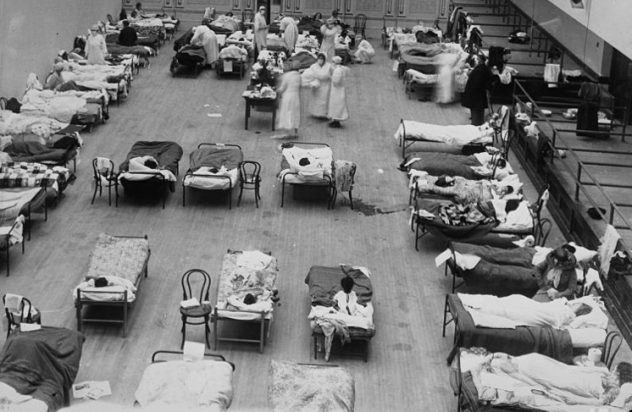

2 The Great Influenza Pandemic

When the Spanish flu appeared in New York in August 1918, the mechanisms of surveillance, isolation, and quarantine clicked into high gear. As cases mounted throughout September, health commissioner Dr. Royal Copeland urged the city to remain calm and tightened disease control measures. The port was closely monitored for sick arrivals from abroad, and the Pennsylvania and Grand Central stations were guarded for local arrivals. Copeland tried to maintain a degree of normalcy by allowing schools and theaters to remain open. Victims hit the thousands in October, and Copeland tried to restrict contact and possible infection among people by easing congestion in public transportation. Business and office hours were staggered to limit the number of people out on the streets at any one time. Theaters were only allowed to remain open if they were well-ventilated and clean. Coughing or sneezing without covering the nose and mouth was made a misdemeanor. Copeland argued that the subway and transport system were more dangerous places than theaters, since sick people would not normally go to a theater but could still go to work. He also believed that keeping children in school, where they could be monitored, offered them better protection against the flu than staying in their crowded, dirty tenements. The schools stayed open throughout the epidemic. Copeland’s strategy was swift isolation of the sick rather than closure of public places. The entire city mobilized against the flu. Community organizations led volunteer nurses and provided food and supplies. People offered their cars as ambulances. Volunteers went from door to door looking for new cases. Vigilant Boy Scouts stopped those spitting on the street, handing them printed reminders saying, “You are in violation of the Sanitary Code.” The city found itself shorthanded in burying the thousands of dead. Fifty street sweepers had to be drafted as gravediggers. Three thousand New Yorkers had to be fed and cared for every day. At one point, Copeland collapsed in exhaustion but was back to work the next day. New cases gradually declined, and the worst had passed by November. New York was able to celebrate the end of World War I (November 11, 1918) with renewed hope. With a death rate of six in 1,000 residents, New York was actually more fortunate than cities like Boston (seven in 1,000) and Philadelphia (7.5 in 1,000). Still, that adds up to a harrowing 20,000 dead in a city of six million.

1 Richmond Hill Train Collision

On November 22, 1950, Train 780, bound for Hempstead, Long Island, left Penn Station at 6:09 PM, filled with passengers anticipating being with their families for Thanksgiving. Four minutes later, Train 174 left Penn for Babylon Station on the same track. The 780 was approaching Jamaica station when its air brakes locked, grinding it to a halt at the Richmond Hills section of Queens (today a part of Kew Gardens). Behind it, the 174 hurtled forward at 56–64 kilometers per hour (35–40 mph). A faulty signal-light system gsve motorman Benjamin Pokorny no warning of the danger in the darkness ahead. As the stalled Hempstead train loomed before him, Pokorny frantically applied the brakes, but it was too late. The 174 barreled through the back car of the 780, slicing it in half lengthwise and sending it 5 meters (15 ft) through the air. Pokorny and 78 people in the back car of 780 were killed. Hundreds of injured were strewn along the tracks. It was one of the worst train collisions in New York history. The surrounding neighborhood rushed to help pull the survivors to safety and to recover the dead. Some amputations had to be done on the spot. The seriously injured were taken to a nearby house that had been transformed into a makeshift operating room. A thousand people showed up to donate blood. Investigations showed that the Long Island Railroad (LIRR), which operated the trains, had no safety devices to prevent such accidents. Subsequently, Automatic Speed Control (ASC) was installed on the tracks. LIRR underwent a 12-year, $58 million improvement program. Larry is a freelance writer whose main interest is history.