Many recognize these truths, and yet few have fully comprehended just how daunting a task it was to settle a strange continent. The following 10 entries will not only provide greater detail about memorable events, but many will also provide a new appraisal of certain moments in history.

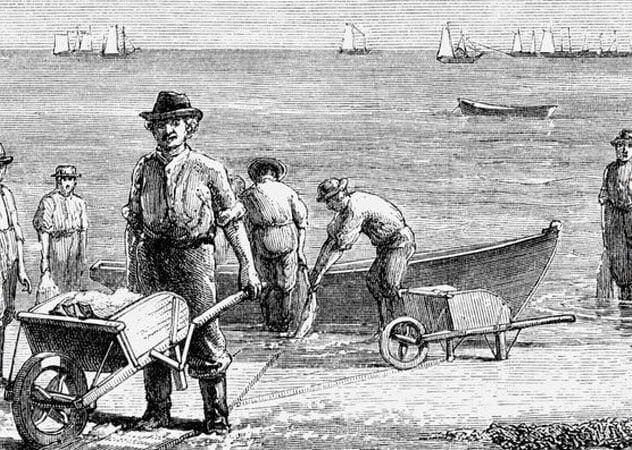

10 The Pre-Pilgrim Settlers Of New England

Most US students can rattle off the dates concerning when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. Most believe that before 1620, no English settlers had ever set foot on New England soil. This, however, is incorrect. In looking through the historical record, it’s clear that isolated English fishing communities from what is now Maine down to Long Island sparsely dotted the map. For the most part, these settlers stuck close to the coast, although it has been asserted that their contacts with the Native Americans led to epidemics that weakened certain tribes prior to the arrival of the Pilgrims. Furthermore, it’s likely that English settlers had been trawling the waters of New England for generations before the coming of the Separatists and Puritans. Indeed, the very fact that Squanto, a member of the Patuxet tribe, could speak English and was a Christian highlights the fact that the English began settling New England long before 1620.

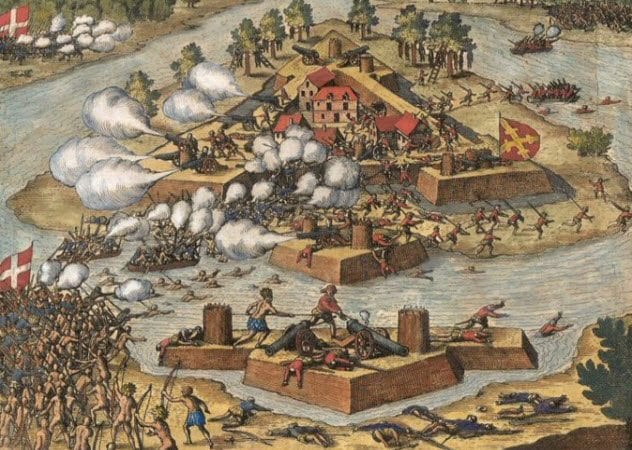

9 The First Pilgrims

Decades before English Separatists sought to leave behind the neo-Catholicism of the Anglican Church, a group of French Protestants, known as the Huguenots, settled in modern Florida. Back in Europe, after years of tense harmony, French Catholics decided to bloodily purge Calvinism from their country. During the infamous Massacre of Saint Bartholomew’s Day in 1572, the Huguenot leader Gaspard II de Coligny was murdered alongside 3,000 Protestants in Paris and another 70,000 throughout France. Seeking refuge from Catholic persecution, many Protestants fled to Fort Caroline near today’s Jacksonville. The fort had been founded by a French expedition led by de Coligny and Jean Ribault. Unfortunately, on September 20, 1565, the small garrison at Fort Caroline was overrun by a Spanish force who reclaimed the area for Catholicism.

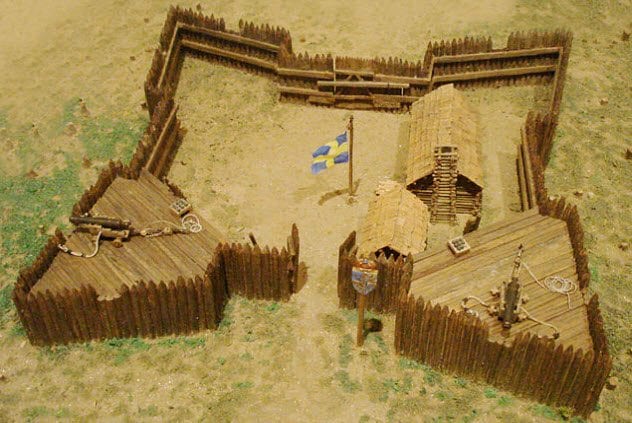

8 Forgotten Conquerors

The pop history of early America usually focuses on the colonies of England, Spain, France, and, to a much lesser extent, the Netherlands. But there was a fourth power involved—Sweden. Between 1638 and 1655, Sweden controlled much of Delaware, southern New Jersey, and eastern Pennsylvania. The center of the colony, Fort Christina, was founded by a small cadre of sailors who left Gothenburg under the command of Captain Peter Minuit. Located in Wilmington, Delaware, Fort Christina included mostly Swedish settlers with a sprinkling of Finnish and Dutch as well. The commercial goals of New Sweden were never fully met. After Sweden lost to Russia in the Second Northern War, the 400 men at Fort Christina became citizens of New Netherland.

7 Battle Of The Severn

Sometimes called the final battle of the English Civil War, the Battle of the Severn took place far away from England in the colony of Maryland. When Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, took control of the colony, he tried to establish it as a refuge for England’s Catholic minority. Unfortunately for him, large Protestant immigration quickly turned Maryland into a Protestant-majority colony. In 1649, Governor William Stone allowed several hundred Puritans from Virginia to settle in Maryland. Years later, Virginia declared its loyalty to King Charles II, the heir of the executed King Charles I. As for Maryland, Governor Stone ordered all landowners to pledge their loyalty to the Catholic Lord Baltimore, which in a way was an oath of allegiance to the English crown. As can be expected, the Puritans refused. So on March 25, 1655, Governor Stone and a militia force sailed from St. Mary’s City to the Puritan settlement of Providence (today’s Annapolis). Near Spa Creek, the Puritans surprised Stone’s men, killing 40.

6 Puritans Return To England

Decades prior to the English Civil Wars, a massive migration of English Protestants took place. Many went to the Netherlands, where Calvinism was accepted. Some went to the Rhineland, while others headed for the Caribbean islands of Barbados and Saint Kitts and Nevis. An unlucky few settled Old Providence Island off Nicaragua’s Mosquito Coast. The majority, however, landed in Massachusetts, thereby creating the Plymouth Colony and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Between 1620 and 1640, over 20,000 Pilgrims and Puritans settled what would become New England with their families. Soon thereafter, the population doubled and would continue to double every generation for two centuries. However, in 1640, large-scale immigration to Massachusetts reversed as Puritans, both English-born and Massachusetts-born, began sailing back to England to fight for the Parliamentarians. While the exact number is unknown, it is true that this Puritan exodus essentially stopped widespread immigration to New England until the Irish Catholic waves of the 1840s.

5 The First French Fort

Throughout the history of New France, the most important colony was Quebec. To this day, Quebec remains the chief Francophone province in Canada. Other former French colonies, from Illinois to Ohio, have lost their Gallic flavor. In 1562, the first French settlement in North America was founded by the Huguenots under the command of Jean Ribault. Called Charlesfort, this short-lived colony collapsed when the 26 or 27 men that Ribault left behind mutinied, built their own ship, and returned to France. The ruins of Charlesfort, or rather Charlesfort–Santa Elena, can be found on Parris Island, South Carolina.

4 The Strict New Haven Colony

Puritanism has a well-earned reputation for theological rigidity. However, even within Puritanism, there were divisions between conservatives and liberals. John Davenport, the founder of the New Haven Colony in Connecticut, was arguably the strictest Puritan of early America. Founded in 1638, the New Haven Colony had a very clear set of rules: Everything had to be done according to the Bible. Not only did colonists pledge to live their lives according to Scripture, but the town itself was laid out in such a way as to resemble the Temple of Solomon and the New Jerusalem of the Book of Revelation. Davenport believed that his colony’s government, exemplified by the Church of the Elect, should be ruled by the laws of the Old Testament and by so-called “saints.” In 1665, New Haven Colony merged with the larger Connecticut Colony.

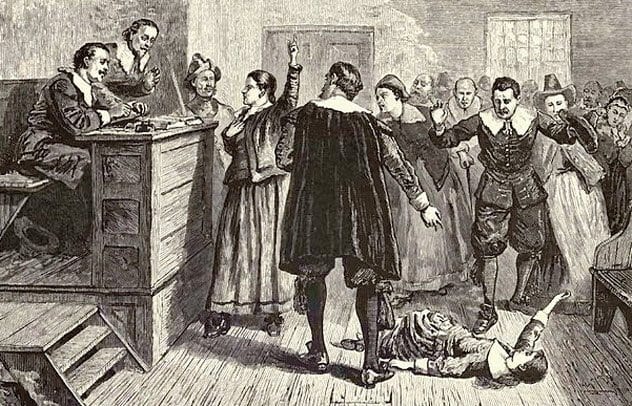

3 Refugees And The Salem Witch Trials

As first argued in the book Salem Possessed by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, many today view the Salem witchcraft trials of 1692 and 1693 as the tragic end result of a land dispute between many of the village’s families. This view is backed up by maps that show the geographic disbursement of the accused and the accusers. One of the lesser-studied aspects of the trials is the role played by refugees. Namely, a few of the accusers, including 17-year-old Mercy Lewis, had recently moved to Salem Village from the frontier settlements of Maine. During King William’s War, which occurred in the background throughout the entire trials, Native Americans raided English settlements in Maine and drove many back to Massachusetts. George Burroughs, the former minister of Salem Village who was accused of leading the witch’s coven, had earlier been accused of bewitching soldiers during his time as the minister of Falmouth (now Portland), Maine.

2 The Massacre Of 1622

The attack on the colony of Jamestown that erupted on the morning of March 22, 1622, proved to be one of the deadliest days in the history of colonial America. Angered by the growing English population and the less than friendly manner of the English colonists who began settling away from the coast, the Powhatan tribe surprised the citizens of Jamestown and ultimately killed 347 of them. The massacre, which was part of a larger Powhatan uprising, nearly ended the English colony of Virginia. One-sixth of all Virginians were killed on March 22, while many others became lost or were taken prisoner.

1 The Worst War In Early America

In terms of sheer body count, the US Civil War remains the deadliest war in American history. In terms of per capita losses, King Philip’s War of 1675–76 is the deadliest. Under the leadership of the Pokunoket chief Metacom (aka King Philip), a confederacy of Native American tribes tried to drive the English settlers back across the sea. The war was especially vicious. By 1680, Native Americans only made up 10 percent of New England’s population. Furthermore, one-tenth of New England’s military-age male population perished during the war, while 12 Puritans towns were burned to the ground. Although the war proved costly, King Philip’s War did much to unite the New Englanders as a separate people. As England did not provide troops, arms, or support, the New England militias fought the war on their own, thus arguably laying the groundwork for an American identity. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet