10Phallic Bricks Of Pompeii

We all know the legend surrounding Pompeii. The original City of Sin’s people basked in a perpetual heat of promiscuity—promiscuity said to have inspired the gods’ rage with the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Since excavation of its near-perfectly preserved remains began in the 18th century, archaeologists have discovered a great deal regarding Pompeii’s sexual identity. Pompeii’s economy thrived on more than 40 brothels, the most famous of which was named “Lupanare Grande,” translated today as “pleasure house.” The rooms in these brothels were often cramped and dim, with a small straw mattress positioned beneath a piece of pornographic artwork hung on the wall. Despite their appearances, it would be misleading to classify these brothels as the seedy underbelly of Pompeii’s economy. Rather, they existed on a highly public and unashamed platform, alongside the forum and communal bath houses, both of which were important sites of a larger (public) sex system. Visit the ruins of Pompeii today, and you will no doubt see the “phallic bricks” of Pompeii pointing the way to the nearest pleasure house with an erect phallus engraved into its stone. And if those weren’t clear enough markers, erect phalluses were often positioned above the doors of brothels and private residences as tidings of good luck.

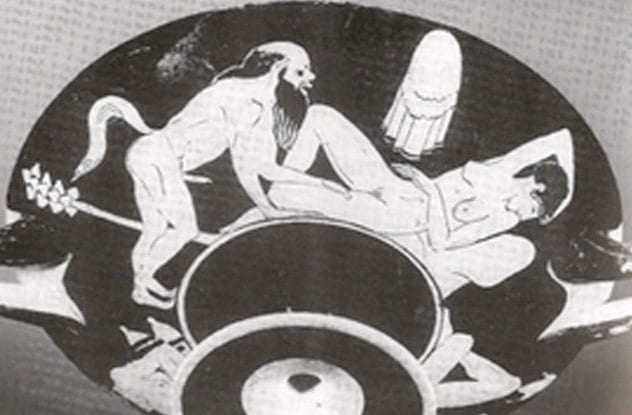

9Voyeurism

“You may look, but don’t touch,” was somewhat of a guiding theme across Ancient Roman and Greek artwork, as indicated by the many pieces of art uncovered today displaying such provocations. One could discover this for themselves at The Gabinetto Segreto in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. This “Secret Cabinet” houses a collection of erotic artwork from Ancient Rome. One such wall painting from, unsurprisingly, Pompeii, displays this voyeurism with a man and a woman having intercourse in front of their attendant, who is visible in the background. In Ancient Greece, there exists a body of art dedicated to Maenads, the feverous female followers of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, ritual madness, religious euphoria, and theatre. Artwork surrounding these women were highly explicit, and the sexual acts represented by the artwork displayed the figures as objects to be observed. This idea of voyeurism in erotic art was twofold, where a voyeur existed within the artwork, as was the case in one hydria painting Sleeping Maenad and Satyrs, as well as external to the artwork, where the onlooker (or “innocent bystander”) also became a voyeur.

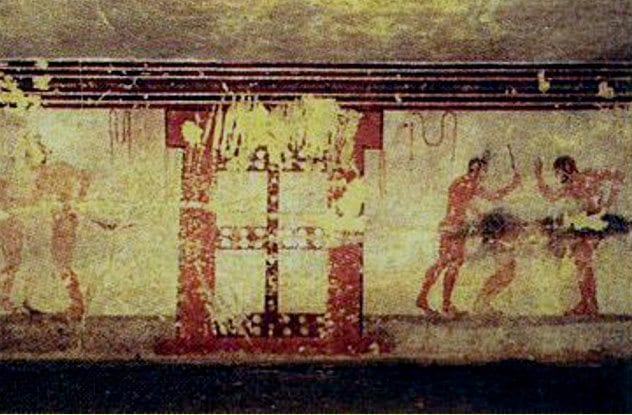

8The Wife-Sharing Economy

The Etruscan civilization was assimilated into the Roman Republic during the fourth century BC. However, their customs remained largely intact. The Etruscan women were known for their liberated attitude toward intercourse and nudity. They kept their bodies in fit condition and often walked around in the nude, enjoying the pleasure of all men who came by. “Marriage” was a loose construct. It was common for children to have no clue who their father was, and for women not to ask. Frescoes painted on the Tombs of The Bulls, The Bigas, and The Floggings, in Tarquinia, display these kinds of erotic scenes.

7Fruitful Contest Of The Sexes

Kenneth Reckford, an expert of the Classics, analyzed Aristophanes’s work in a series of essays entitled Aristophanes’s Old-and-New Comedy. One essay, “Aischrologia,” addresses the season ritual of Thesmophoria in Ancient Greece. Only married Athenian women participated in this ritual, which aimed to promote fertility. In preparation, women would abstain from intercourse and oftentimes bathe as an act of purification. During this three-day affair, women would perform various acts of “fertility magic.” In addition, they would share lewd jokes and tales of their indecencies, and play with toys replicating both the male and female genitals. This ritual, coupled with the Eleusinian Haloa festival, gave women the opportunity to release pent-up sexual frustration through liberal use of sex symbols, pornographic sweets, raucous activities, and free-range slut-shaming—for lack of a better phrase. During Haloa, according to Reckford, Greek women could “say the most ugly and shameful things to one another,” shooting insults at each other regarding sexuality and vulgarity, while proclaiming their own indiscretions.

6Fun At The Carnival

According to Mikhail Bakhtin, a scholar of literary theory and philosophy, the Carnival of ancient literature was a free-for-all, where people would throw class division, respect, and sensitivity out the window. There was no “saying no,” and certainly no saying “too much.” Carnival was pure id. Suspend reality and imagine a scene of extravagance, with banquets of food and wine, laughter, and sex. At Carnival, everyone was equal, and even degrading remarks inspired a regenerative energy—though, that may be in part due to the number of drugs and intoxicants they used to strip inhibitions. Arthur Edward Waite in his book A New Encyclopedia of Freemasonry says, “The Festivals were orgies of wine and sex: there was every kind of drunkenness and every aberration of sex, the one leading up to the other. Over all reigned the Phallus.” These Carnival rituals date back to as early as the fifth century BC and were held during the spring equinox. It should come as no surprise that these festivals, called The Dionysian Mysteries, were dedicated to Dionysus, the Greek god of all your earthly desires and the enabler of all your poor decision-making. This carnival inspired the Roman equivalent, Bacchanalia. Most of the initiation process for men and women are known thanks to a collection of frescoes preserved in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii. And, in all fairness, it is a bit reminiscent of what one might expect in Greek life initiation today. The murals a declaration of initiation at the feet of the priestess followed by a descent into the underworld (katabasis), before returning anew. Aristophanes, in his play The Frogs, assumes the origin of this ritual with descent of Dionysis into Hades.

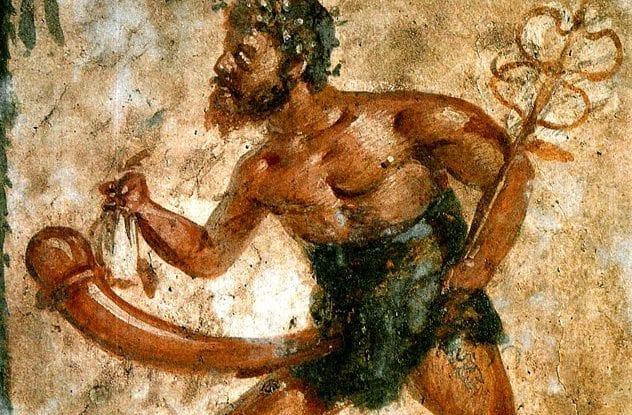

5Before Viagra, There Was Priapus

The Greeks had a very firm relationship with the phallus—more an obsession, really. In particular was Priapus, the Greek god equivalent to Dionysus, known for his extremely long and permanently erect penis. If you think you recognize the term, it’s because Priapus inspired the medical term priapism. And even if Priapus didn’t play too well with the other gods, he was revered on Earth. The Priapeia contains a collection of 95 poems dedicated to the sexually driven vulgarity of Priapus. With this gift of dirty pictures from the tract of Elephantis Lalage asks if the horny deity could help her do it just like in the illustrations The law which (as they say) Priapus coined for boys appear immediately subjoined “Come pluck my garden’s contents without blame if in your garden I can do the same.”

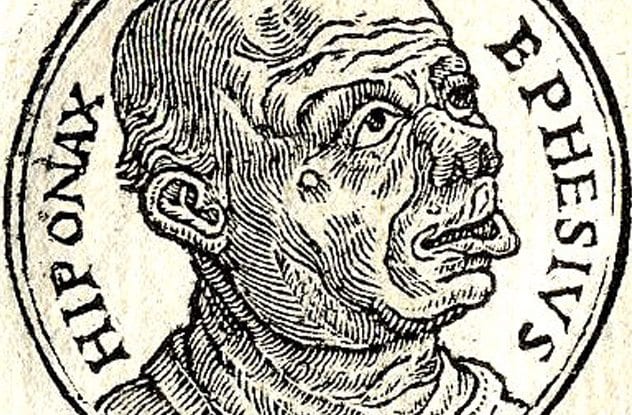

4They Threw Some Serious Shade

Hipponax of Ephesus was a highly controversial iambic poet, even for ancient Greece. Where he excelled were his insults, which were raunchy and lewd and often satirical of the high (dignified) language of his targets. In fact, as the story goes, he was so skillful at insults, they drove one victim to suicide. Hipponax was apparently after the daughter of Bupalus, but Hipponax’s deformed looks ultimately led to his rejection. In jest, Bupalus made a statue of Hipponax so ugly that Hipponax retaliated with accusations of Bupalus having an incestuous relationship with his mother: “Bupalus, the mother-f—r with Arete, fooling with these words the Erythraeans preparing to draw back his damnable foreskin” Other notable shade interpreted in Hipponax’s work includes the dissection of Bupalus’s name, Bou-phallus, meaning quite literally “ox phallus,” and the ever-charming “interprandial pooper,” meaning a person who must get up during the middle of a meal to defecate.

3Using Sex For World Peace

Aristophanes, considered one of the most famous comic playwrights of ancient Greece, was known for his poignant commentary of the social and political landscapes of Athens during the late fifth and early fourth centuries BC. In one such play, Lysistrata, Aristophanes parodies warfare with a battle of the sexes. The women use the men’s desires against them, forcing abstinence to compel peace between the Athenians and the Spartans. Women thus use their sexuality to put things in perspective for men, and to ultimately remind them of the “transcendental significance” of sex. According to the women, the men had forgotten this amidst their stubbornness over more trivial matters, like war. In the end, Peace appears to the men as a young, naked woman to remind the men of their sexual desires to “plow a few furrows” and “work a few loads of fertilizer in.” The men, in turn, realize the importance of sex to their society enough that they put war behind them.

2“Ars Amatoria”

A short cry from Karma Sutra was the work of one Ancient Roman poet, Ovid (43 BC–AD 17). His work provided instruction for sexual proclivities, with titles including “Amores” (Love), “Medicamina Faciei” (Remedies for Love) “Remedia Amoris,” and most infamously, “Ars Amatoria” (the Art of Love). While his work may sound wholesome, Ars Amatoria became a guidebook for lovers and adulterers alike. In many ways, he created The Game, which confuses both men and women to this day. He advises men to let their women miss them—but not too much, while advising women to make their men jealous at times, to ensure they do not grow lax nor lazy. In the bedroom, Ovid details what form women should take, to not only maximize pleasure for themselves, but also to make it most pleasurable to the man’s gaze. In one sense, he moved away from the notion of women as possession—as they were equal players in the game of love—while on the other hand, reinforcing manipulative tactics to keep one’s lover constantly on their toes. Though his language never broke into vulgarity, it was quite explicit in its detail, and in a matter of poor timing, resulted in his exile by Augustus, who was still coping with the news of his daughter’s copulations.

1Martial

As with other emotional impulses, shock lies in the space between expectations and reality. Marcus Valerius Martialis, or Martial, was a Roman poet from first century, who was made famous by his 12 books of epigrams. To this day, Martial’s epigrams are shocking due to their obscene, and oftentimes graphic, language. If nothing else, their vulgarity sheds light on the type of work published at the time. Epigrams 79 and 80 of Book III convey vulgarity in a distinct structure. In these epigrams, insults are initially targeted at the subjects’ character and are then redirected by insulting subjects’ sexual “short-cummings.” In Epigram 79, Martial begins by declaring: “Sertorius finishes nothing, and starts everything. When he fornicates, I don’t suppose he completes.” Martial’s sharp words pivot this insult more pointedly at Sertorius’s sexual incapability. Likewise, Epigram 80 introduces its subject with a more general observation followed by a hyper-sexualized observation. “You talk of nobody, Apicius, speak ill of nobody, yet rumor says you have an evil tongue.” While the former could pose as a general remark to Apicius’s soft-spoken character, the latter angles the reader to the true central insult: Apicius’s skill at oral sex. Here, “evil” is more likely a term for “wild,” suggesting that Apicius’s tongue causes his sexual partner to lose control and that he is skillful at giving head. The explicit quality of this language indicates the level of tolerance Ancient society had at the time regarding sex. Emma Marie is a student, photographer, traveler, and certified freediver.