10The 20-Year Search For A Missing Opera

Enrique Granados, a renowned Spanish composer, wrote an unpublished opera called Maria del Carmen in 1898. The story of a love triangle in Murcia, the opera was so celebrated when it opened in Madrid that the Queen of Spain gave Granados the distinguished Charles III Cross for his music. Even so, the original version of the opera was never performed again. When the New York Metropolitan Opera performed another of the composer’s works in 1916, Granados and his wife sailed to America with the only copy of Maria del Carmen. Granados hoped to persuade the Met to perform his masterpiece. When they didn’t agree, the Granados set sail to Spain via England, but a German submarine torpedoed their boat in the English Channel. The couple drowned, but the three-volume opera survived, as did their six children whom they’d left in Barcelona. Two decades later, a son who needed money sold the opera to an American musician against the wishes of other family members. For the next few decades, the music’s ownership was litigated. Before the issue was settled, the opera was supposedly destroyed in a New York warehouse fire in 1970. A couple of decades later, Walter Clark, a graduate student writing a dissertation on music, learned of the missing masterpiece. For the next 20 years, he couldn’t shake his doubts about its fate. “I wondered if it was really destroyed,” Clark said. “No one had done a proper inventory after the fire. When I was researching my [2006 biography of Granados], I contacted the grandson of the man who had purchased Maria, and he kept looking.” Finally, in 2009, the opera was found, although it had been damaged by smoke and water. Thanks to the music professor who played detective, Maria del Carmen has been restored and subsequently published by the company, Trito. For the first time since 1899, the opera will also be performed in Spain in 2015.

9The Moroccan Village Built On A Rock Pile

At about 3,900 meters (13,000 ft) above sea level, the village of Arroumd sits perilously atop a huge pile of rocks in the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco. For over 130 years, the origin of that rock pile has mystified scientists. Most assumed the movement of a glacier deposited the rocks, but modern dating techniques point to seismic activity 4,500 years ago as the culprit. The village is located near a major tectonic fault that sits below the face of a cliff. Although a glacier probably eroded the face of the cliff, making it vulnerable to collapse, the avalanche occurred approximately 7,000 years after the glacier melted. So the glacier may have made the cliff more likely to collapse, but an earthquake was probably the actual trigger of the avalanche of rocks. Even beyond the huge pile of rocks, Arroumd is a mysterious place. “Several incidents occurred at the site, including some accidents—minor, thankfully–and mystery ailments to those who went there,” said lead researcher Philip Hughes. “I always joke about the ‘curse’ of the Arroumd landform. This year, we encountered severe whirlwinds when entering the valley . . . We were unable to stand on our feet, which is rather unusual for this part of the world, where climate is often hot and calm.”

8How Mary Ingalls Really Went Blind

In the Little House on the Prairie children’s book series, author Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote that her real-life sister, Mary, was blinded by scarlet fever at age 14. The event was also dramatized on a television series based on the books. But pediatricians say the explanation for Mary’s blindness doesn’t make sense. Dr. Beth Tarini was surprised by that discovery even as a medical student. “I was in my pediatrics rotation,” said Tarini. “We were talking about scarlet fever, and I said, ‘Oh, scarlet fever makes you go blind. Mary Ingalls went blind from it.’ ” Her professor disagreed, which propelled Tarini on a detective mission to find out what really happened to Mary. Tarini and her team researched the issue for 10 years. They found that Mary had scarlet fever as a young child, but her illness at 14 was referred to as “brain fever.” There was also no reference to her having the distinctive rash of scarlet fever as a teenager. While scarlet fever had a mortality rate for children of up to 30 percent in the 1800s, most cases of blindness from the disease were temporary. As the team continued to investigate, they discovered that Laura wrote a letter to her daughter, Rose, in 1937 describing Mary’s illness. Laura sent the letter right before the publication of her book By the Shores of Silver Lake, which described Mary’s blindness as being caused by scarlet fever. However, an excerpt from the letter stated: “Mary had some sort of spinal sickness. I am not sure if the Dr. named it. We learned later when Pa took her from De Smet, South Dakota to Chicago, Illinois to a specialist that the nerves of her eyes were paralyzed and there was no hope.” After poring over historical records, including the Ingalls’ town newspaper that reported that Mary had suffered from severe headaches and partial paralysis on one side of her face, the researchers now believe that Mary contracted viral meningoencephalitis, which inflames the brain and spinal cord. By inflaming the optic nerve, it can also lead to blindness.

7Gospel Of The Lots Of Mary

Recently translated by Princeton University religion professor Anne Marie Luijendijk, the 1,500-year-old “Gospel of the Lots of Mary” is not a gospel describing the life and death of Jesus Christ, as everyone had assumed. Instead, it’s a sort of Magic 8 Ball to predict the future and help people solve their problems. This Christian oracle book was written in the Egyptian Coptic language, which uses the Greek alphabet. The book opens like this: “The Gospel of the lots of Mary, the mother of the Lord Jesus Christ, she to whom Gabriel the Archangel brought the good news. He who will go forward with his whole heart will obtain what he seeks. Only do not be of two minds.” That opening led Luijendijk to believe the book contained a standard type of gospel. However, she found that the heavily used book was made up of 37 oracles, which rarely mentioned Jesus. If a person needed help with a problem, he would ask a question of the book’s owner. Then they would select an oracle at random to solve the problem. The book’s owner would interpret the oracle’s answer. Each oracle is written so vaguely that it could be used for many situations. An example would be: “Stop being of two minds, o human, whether this thing will happen or not. Yes, it will happen! Be brave and do not be of two minds. Because it will remain with you a long time and you will receive joy and happiness.” Ancient “lot books” were consulted to predict people’s futures. Overall, this book takes a positive view of what lies ahead. However, Luijendijk had never known of another lot book that was referred to as a “gospel,” which translates as “good news.” That leads Luijendijk to believe that gospels may have been viewed differently in ancient times, perhaps not solely as texts about the life and death of Jesus. In 1984, the text was donated to Harvard University by the daughter-in-law of an antiquities trader. However, no one knows how or when the family acquired the book.

6Why Palmyra Was Located In The Syrian Desert

Palmyra was an important trading hub in the Roman Empire around 2,000 years ago. But historians could never understand how Palmyra’s 100,000 residents were able to thrive in the middle of the Syrian desert—or why they would live there in the first place. However, a team of Norwegian and Syrian researchers has finally solved the mystery. Palmyra and over three dozen surrounding (but forgotten) ancient Roman farming villages used a network of water reservoirs to make their arid steppe green. By collecting and channeling the yearly rainfall of 12–15 centimeters (5–6 in) from seasonal storms into these reservoirs, the ancient inhabitants farmed the land with a variety of crops. This gave Palmyra a stable source of food, even during droughts, making it a grand oasis of avenues, arches, and columns in a vibrant desert marketplace. The city also prospered as a major trading hub linking Eastern civilizations with Western ones. Although the Persians and Parthians controlled the East and the Romans dominated the West, there were small independent kingdoms located between the two. Each of their rulers demanded payments from travelers to use their water routes—along parts of the Euphrates and Nile Rivers, for example. Rather than pay all those exorbitant river taxes to take the direct routes, tradesmen would cut through the desert and stop at Palmyra. There, they could purchase the items and services they needed to safely complete their journeys. This greatly contributed to Palmyra’s prosperity in ancient times.

5The Shape Of Stonehenge

For a long time, historians have been divided on whether the stones at Stonehenge had originally formed a full circle. With no stones found in the southwest area, some researchers believed the structure had never been completed. But a short hosepipe accidentally solved the mystery without excavation or expensive equipment. Tens of thousands of people had earlier overlooked the answer. When a custodian couldn’t water the grass in the entire Stonehenge area (as was usually done) due to the short hose, the grass failed to grow in the unwatered area, revealing depressions in the ground. If some of those parched areas had held stones, the circle would have been complete. Other brown patches matched areas of known archaeological excavations, confirming that the parched areas represented ground that had been intentionally disturbed. “A lot of people assume we’ve excavated the entire site and everything we’re ever going to know about the monument is known,” said historian Susan Greaney of English Heritage. “But actually, there’s quite a lot we still don’t know and there’s quite a lot that can be discovered just through non-excavation methods.” That still leaves the mystery of what happened to the missing stones. Were they used to build houses or roads in the area? No one knows, but English Heritage may purposely avoid watering some areas of Stonehenge during the next dry spell to see if the answers to other puzzles emerge.

4The Disappearance Of The Nazca Civilization

For years, historians were baffled by the mysterious disappearance of the Nazca people of Peru around A.D. 500. This was the civilization responsible for the Nazca lines, huge geoglyphs carved into the ground in that region. There have been many theories to explain the lines, but most historians agree that the Nazca probably used them as sacred pathways when practicing their rituals. In recent years, scientists have determined that the Nazca civilization caused its own destruction. By clearing so many huarango trees in their valleys for farming, they did irreparable damage to their environment. These nitrogen-fixing trees increased moisture and soil fertility. Without enough of them, the climate became too arid to grow food. “The huarango . . . was an important source of food, forage, timber, and fuel for the local people,” said archaeologist David Beresford-Jones. The species was responsible for “enhancing soil fertility and moisture, ameliorating desert extremes in the microclimate beneath its canopy and underpinning the floodplain with one of the deepest root systems of any tree known. In time, gradual woodland clearance crossed an ecological threshold—sharply defined in such desert environments—exposing the landscape to the region’s extraordinary desert winds and the effects of El Nino floods.” Scientists believe that a major El Nino event occurred around the same time as the deforestation, triggering devastating floods due to the lack of trees. After that, the Nazca would have been unable to grow enough food for their people in that area.

3A War Bracelet Comes Home

While serving in the Army during World War II, Warren McCauley lost or left his silver identification bracelet (“dog tag”) in Castel D’Aiano, Italy in 1945. According to an Army news release that year, war hero McCauley received the Bronze Star when he “fearlessly advanced under a hail of small-arms fire to restore communications” after the German enemy cut wire lines. While in Castel D’Aiano, McCauley stopped at the de Maria home, which the Italian family had opened to American soldiers for food and medical care. When McCauley left, his bracelet stayed behind, although no one knows if he lost it, forgot it, or left it on purpose as a kind of payment or tribute to the de Maria family. Nevertheless, Bruna de Maria, then eight years old and living there in poverty, found the bracelet and kept it as an unexpected treasure. She always lovingly cared for the bracelet but never tried to find its owner. Decades later, her grown son, Stefano Sedda, persuaded his mother to return her treasure to its original owner. “This bracelet made history,” Sedda explained. “It belonged to an American soldier who came here to fight, to defend our country—that’s why I thought of giving it back.” Through a friend, Sedda contacted an American lawyer, who worked with a journalist and the Army to trace the bracelet’s ID number to McCauley. Though McCauley had died 30 years earlier, they found his 85-year-old widow, Twila McCauley, living in Buena Vista, California. Warren McCauley had shared some wartime stories with his family—like the time he fell into a river and a donkey walked over him—but he’d never told them about the bracelet. Along with the rest of her family, Mrs. McCauley was touched and grateful to have this special connection to her late husband brought home almost 70 years after it went missing.

2The Cambyses Cover-Up

As we’ve discussed earlier, the lost army of Persian king Cambyses II has been a great historical mystery. Around 524 B.C., the king ordered 50,000 men into the Egyptian desert around the ancient city of Thebes (now Luxor). When the men disappeared, the official story from ancient historians said the army had been wiped out by a sandstorm. However, modern Egyptologist Olaf Kaper was skeptical. “Since the 19th century, people have been looking for this army: amateurs, as well as professional archaeologists,” Kaper said. “Some expect to find somewhere under the ground an entire army, fully equipped. However, experience has long shown that you cannot die from a sandstorm, let alone have an entire army disappear.” By piecing together information from excavations, historical records, and especially the writings of an Egyptian rebel leader (which Kaper had translated from ancient temple blocks), Kaper believes the Persian army was on its way to Dachla Oasis, where the rebel leader Petubastis III and his troops had been located. But the Persian army was ambushed by the rebel leader and suffered a crushing defeat. From his victory, Petubastis went on to reconquer much of Egypt and crown himself Pharaoh in the capital of Memphis. According to Kaper, the Persian king Darius I put an end to this Egyptian rebellion in a bloody battle two years after Cambyses was defeated. To restore Persia’s dignity, Darius covered up his predecessor’s embarrassing downfall with the sandstorm story.

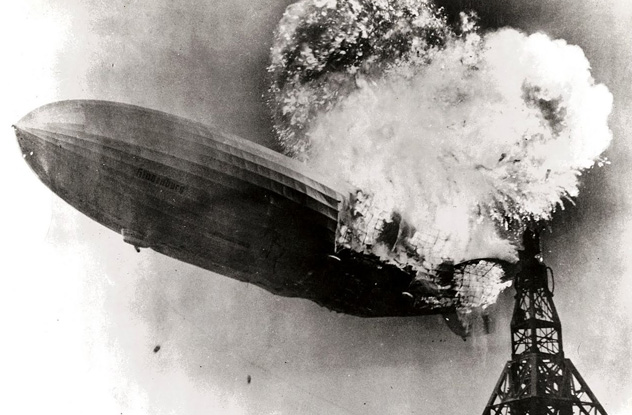

1What Caused The Hindenburg Explosion

The promise of the Hindenburg, a hydrogen-filled airship that could cross the Atlantic in half the time of a ship at sea, exploded along with the craft itself as it prepared to land in Lakehurst, New Jersey in May 1937. Of the 100 people on board that day, 35 died. Scientists have debated the reason for the explosion for decades. They knew that a spark ignited leaking hydrogen, but they differed on the reason for the spark and the leaking gas. Theories included lightning, explosive properties in paint, and a bomb. However, in 2013, a team of experts ruled out the other theories and determined that the Hindenburg had become charged with static electricity from a thunderstorm. Either a faulty gas valve or broken wire caused hydrogen to leak into the ventilation shafts. A spark of static electricity ignited the hydrogen, which started the fire in the tail section and led to the explosion. “I think the most likely mechanism for providing the spark is electrostatic,” said British aeronautical engineer Jem Stansfield. “That starts at the top, then the flames from our experiments [blowing up or setting fire to scale models of the airship] would’ve probably tracked down to the center. With an explosive mixture of gas, that gave the whoomph when it got to the bottom.”