The Romans learned it from their neighbors and used it especially in the provinces, mostly to discipline their subjects and discourage rebellions. Little did the Romans imagine that the crucifixion of a humble Jew in a lost corner of their territory would give the crucifixion an enduring fame.

10 Crucifixion In Persia

Many ancient rulers used crucifixion to send a message to their subjects about the things they should not be doing. During the reign of Persian king Darius I (r. 522–486 BC), the city of Babylon dismissed the Persian authorities and revolted against them around 522–521 BC. Darius launched a campaign to recapture Babylon and laid siege to the city. The gates and walls of Babylon held for 19 months until the Persians broke the defenses and stormed the city. Herodotus (Histories 3.159) reports that Darius stripped away the wall of Babylon and tore down all its gates. The city was returned to the Babylonians, but Darius decided to send a message that revolts would not be tolerated by crucifying 3,000 of the highest-ranking Babylonians.

9 Crucifixion In Greece

In 332 BC, Alexander the Great captured the Phoenician city of Tyre, which was being used as a naval base by the Persians. This was accomplished after a long siege that lasted from January until July. After Alexander’s army broke the defenses, the Tyrian army was defeated and some ancient sources claim that 6,000 men were killed that day. Based on Greek sources, the ancient Roman writers Diodorus and Quintus Curtius reported that Alexander ordered the crucifixion of 2,000 survivors of military age along the beach.

8 Crucifixion In Rome

Crucifixion was not a general form of capital punishment under Roman law. It was only allowed under specific circumstances. Slaves could be crucified only for robbery or rebellion. Roman citizens were immune to crucifixion unless they were found guilty of high treason. However, during later imperial times, humble citizens could be crucified for specific crimes. In the provinces, the Romans employed crucifixion to punish what they referred to as “unruly” people who were sentenced for robbery and other types of crimes (Metzger and Coogan 1993: 141–142).

7 Spartacus’s Revolt

Spartacus, a Roman slave of Thracian origin, escaped from a gladiator training camp in Capua in 73 BC and took about 78 other slaves with him. Spartacus and his men exploited the pathological concentration of wealth and social injustice of Roman society by recruiting thousands of other slaves and destitute country folks. He eventually built an army that defied Rome’s military machine for two years. Roman General Crassus ended the revolt, which was the setting for one of the most famous cases of mass crucifixion in Roman history. Spartacus was killed, and his men were defeated. The survivors, more than 6,000 slaves, were crucified along the Via Appia, the road between Rome and Capua.

6 Crucifixion In The Jewish Tradition

Although the practice of crucifixion is not explicitly mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as a Jewish form of punishment, it is suggested in Deuteronomy 21.22–23: “And if a man have committed a sin worthy of death, and he be to be put to death, and thou hang him on a tree: his body shall not remain all night upon the tree, but thou shalt in any wise bury him that day.” In ancient rabbinic literature (Mishnah Sanhedrin 6.4), this was interpreted as the exposure of the body after the person was killed. But this view contradicts what is written in the ancient Temple Scroll of Qumran (64.8), which says that an Israelite who commits high treason must be hanged so that he dies. Jewish history records a number of crucifixion victims. Perhaps the most notable is reported by the ancient Jewish writer Josephus (Antiquities 13.14): The king of Judaea Alexander Jannaeus (126–76 BC) crucified 800 Jewish political enemies who were considered to have committed high treason.

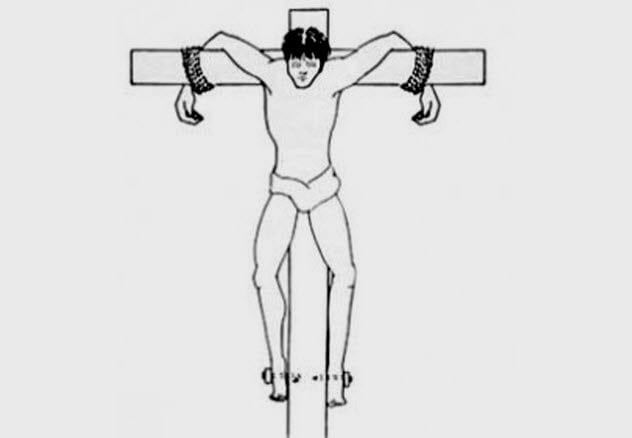

5 The Position Of The Nails

The idea that the nails pierce the victim’s palms is the dominant image we get from painters and sculptors who have represented the crucifixion of Jesus. Today, we know that nails through the palms are unable to support the body weight and likely to strip out between the fingers. Therefore, it is possible that the upper limbs of the victim were tied with ropes to the crossbeam to provide additional support. There is, however, a simpler solution. The nails could be inserted between the ulna and the radius rather than the palms. The bones and tendons of the wrist are strong enough to hold the weight of the body. The only problem with piercing the wrists is that it contradicts the description of Jesus’s injuries in the gospels. For example, in John 24:39, it is stated that Jesus had his hands pierced. Many scholars have tried to explain this contradiction with boring and predictable claims about errors in translation. The reality is that none of the authors of the gospels had been direct witnesses of the events. The earliest of the gospels, the Gospel of Mark, dates to c. AD 60–70, about a generation after Jesus’s crucifixion, so it is not reasonable to expect a high degree of accuracy in such details.

4 Roman Method

There was not a standard way of conducting a crucifixion. The general practice in the Roman world involved a first stage where the condemned was flagellated. Literary sources suggest that the condemned did not carry the whole cross. He only had to carry the crossbeam to the place of crucifixion, where a stake fixed to the ground was used for multiple executions. This was both practical and cost-effective. According to the ancient Jewish historian Josephus, wood was a scarce commodity in Jerusalem and its vicinity during the first century AD. The condemned was then stripped and attached to the crossbeam with nails and cords. The beam was drawn by ropes until the feet were off the ground. Sometimes, the feet were also tied or nailed. If the condemned was able to endure the torture for too long, the executioners could break his legs to accelerate death. The Gospel of John (19.33–34) mentions that a Roman soldier pierced the side of Jesus while He was on the cross, a practice to ensure that the condemned was dead.

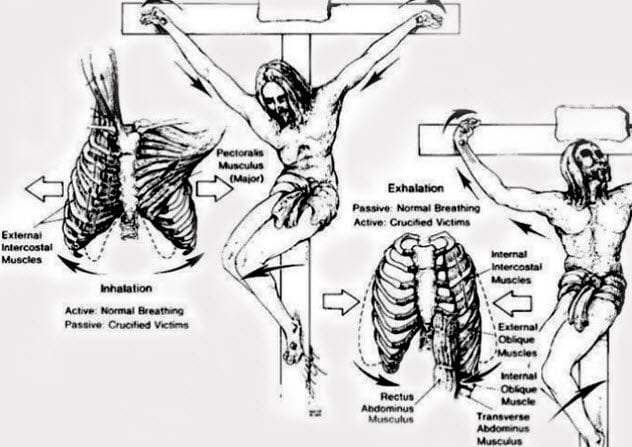

3 Causes Of Death

In some cases, the condemned could die during the flagellation stage, especially when bone parts or lead were added to the whips. If the crucifixion occurred on a hot day, the loss of fluid from sweating coupled with the loss of blood from the flagellation and injuries could lead to death from hypovolemic shock. If the execution occurred on a cold day, the condemned could die from hypothermia. Neither the traumas caused by the nail injuries nor the bleeding were the prime causes of death. The position of the body during the crucifixion produced a gradual and painful process of asphyxiation. The diaphragm and intercostal muscles involved in the breathing process would become weak and exhausted. Given enough time, the victim was simply unable to breathe. Breaking the legs was a way to accelerate this process.

2 Forensic Evidence

Analysis of the bones of a crucifixion victim published in the Israel Exploration Journal has revealed a form of crucifixion that is rarely displayed on paintings or mentioned in literary sources. In this case, the bone injuries showed that the nails penetrated the side of the heel bone. Rather than the traditional position of the legs that we see in many depictions of crucifixion victims, the study suggests that “the victim’s legs straddled the vertical shaft of the cross, one leg on either side, with the nails penetrating the heel bones.” This study also explains why the remains of crucifixion victims are sometimes found with the nails. Apparently, the condemned man’s family found it impossible to remove the nails, which were normally bent due to the hammering, without destroying the heel bone. “This reluctance to inflict further damage to the heel led [to his burial with the nail still in his bone, and this, in turn, led] to the eventual discovery of the crucifixion.”

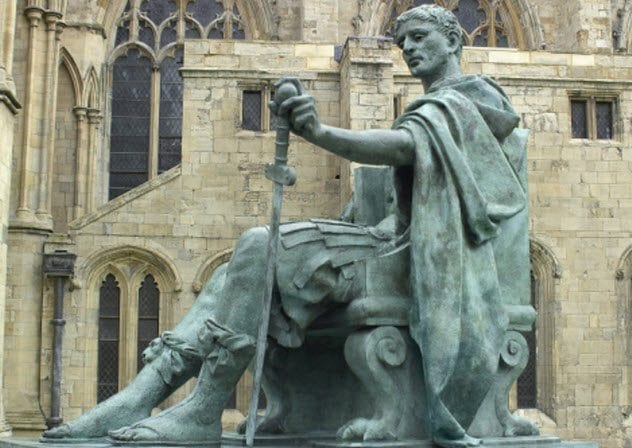

1 Abolition By Emperor Constantine

Under the Romans, Christianity underwent a surprising transformation. It started as an offshoot of the Jewish religion, turned into an outlaw cult, became a tolerated religious expression, developed into a state-sponsored faith, and finally became the hegemonic religion of the late Roman Empire. The Roman emperor Constantine the Great (AD 272–337) proclaimed the Edict of Milan in AD 313, decreeing the tolerance of the Christian faith and granting Christians full legal rights. This crucial step helped Christianity become the official Roman state religion. After centuries of practicing crucifixion as a torture and execution method, Emperor Constantine abolished it in AD 337, motivated by his veneration for Jesus Christ. Read More: Twitter Facebook Ancient History Encyclopedia