It was submitting to a life of long days, mediocre meals, horrendous sanitation, separation from the rest of your family, and a high likelihood you wouldn’t see your freedom again. Workhouses were dark, dismal places, and some heartbreaking stories came out of them.

10 The Andover Workhouse Scandal

We all know that conditions in the workhouses were grim. The general populations of Georgian and Victorian Britain knew it, too. But there’s a difference between having a general idea that workhouse life was difficult and actually hearing about some of the specific horrors that occurred. Houses were run by masters and matrons. Guardians under the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 were supposed to make regular visits to the houses to ensure they were run in accordance with the law. In 1845, previously overlooked conditions at the Andover institution came to light, with rumors of the cruelty finally reaching the ears of someone who would do something about it. Its master was so bad that 61 people from the workhouse committed major crimes between 1837 and 1845 just to be sent to jail and out of the workhouse. Until the Andover scandal, a common task assigned to inmates was bone crushing, with animal bones ground into powders to be used as fertilizer. But starving inmates nearly caused a riot as they fought over discarded bones, trying to eat the marrow inside. In testimony from trials that investigated the cruel conditions, some inmates who were supposed to grind bones revealed that others often stole those bones to eat the marrow or chew on them. Children ate the food waste and raw potatoes they were supposed to feed the pigs, women were often sexually assaulted, and inmates who disobeyed orders were sometimes forced to sleep in the workhouse’s morgue as punishment. Once these conditions became publicly known, the head of the institution was fired. The laws supposedly protecting Britain’s poorest citizens were also overhauled. However, we still don’t know the exact details of what happened behind Andover’s closed doors at that time.

9 Timothy Daly Inspires Florence Nightingale

In December 1864, there was an inquest into the death of an Irish man named Timothy Daly. At the Holborn Union Workhouse infirmary, the 28-year-old Daly was treated for acute rheumatism for six weeks. Then he was taken home and finally admitted to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital a week later. He died the next day. The inquest determined that he died from bedsores and extreme exhaustion caused by neglect at the Holborn infirmary. Even if he had survived, the investigating medical officers believe he would have been permanently crippled from the sores that opened all the way to the bones of his hips. Further investigation revealed his horrifying treatment. Confined to a bed about 0.8 meters (2.5 ft) wide and only a bit longer than his height, he developed bed sores after about four weeks. He and his bedding were dirty, his sores were treated only once with a poultice of beer grounds and linseed, and his bandages were never changed. Daly said that he had seen the doctor walk past him many times, but the doctor had never stopped. This was about the same time that Florence Nightingale was campaigning for an overhaul of the medical facilities in workhouses. Daly’s death was the tragedy cited in her letters to the Poor Law Board, urging them to do something or be responsible for more deaths. It finally got their attention. By January 1865, the overhaul she so desperately wanted was in its planning stages. She would later write to a friend, “I was so much obliged to that poor man for dying.”

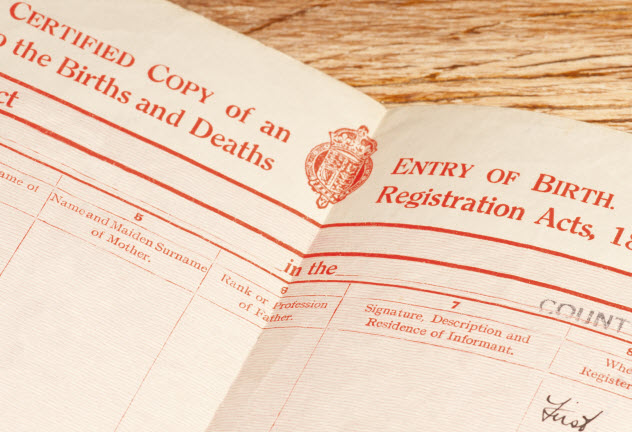

8 Euphemistic Addresses

Whether you admitted yourself or were born into a workhouse, it carried a stigma that would stay with you for the rest of your life. That stigma was so great that laws were changed in 1904 to help children born in a workhouse to escape the cloud that followed them. Before then, a birth certificate reflected the name of the workhouse into which a child was born. But after the laws were changed, new addresses were used instead. Although that made it challenging to research an affected person’s family history, most workhouses used the same name on all birth certificates. For example, the Pontefract institution was listed as 1 Paradise Gardens in Tanshelf, Pontefract, Barton-upon-Irwell became known as 21 Green Lane in Patricroft, Eccles, and Bristol was listed as 100 Manor Road in Fishponds, Bristol. Sometimes, the address corresponded to the actual address of the institution but not always. Liverpool was recorded as 144A Brownlow Hill, even though that address didn’t exist. In some cases, when the street address referred to “workhouse,” the address was changed to eliminate it. By 1918, the same thing was done to death certificates because the stigma of dying in a workhouse also followed a family. In 1921, Scotland changed their laws as well.

7 The Luxurious Rowton Houses

Sometimes, the best indication of how bad things are can be seen in what’s considered a luxury. In 1892, Lord Rowton opened the first of his Rowton Houses. They were designed to be an affordable alternative for people needing a place to spend the night. Rowton financed the construction of the hostels, the first of which had 470 cubicles, and made sure they were state of the art. There were clean sheets on all the beds, enough hot water for all the building’s occupants to get washed after work, a place to dry clothes, and tiled bathrooms with hooks so people could keep track of their belongings. Each cubicle even had its own window. Surprisingly, the homes had modern luxuries such as their own libraries, reading rooms, and writing rooms. They also employed their own shoemaker and provided stores where lodgers could buy their necessities at affordable prices. Unlike traditional workhouses, lodgers had access to salads, milk, coffee, tea, and fresh vegetables. Officially designated as hostels, they weren’t subject to the same rules as other workhouses or hotels. The first Rowton Houses were hugely popular, so more were built. The next ones were even larger than the first. From World War I on, Rowton Houses were home to countless servicemen returning from war and needing to find their feet. During World War II, they were invaluable shelters for refugees and temporary accommodations for families fleeing the city. After the war, they mainly housed elderly residents.

6 William Crooks

For many people, poverty in Georgian and Victorian Britain was a vicious cycle, impossible to escape. But occasionally, someone did. Born to a poor family as one of seven children, eight-year-old William Crooks was sent to the Poplar union workhouse with most of his family after his father lost his arm in an accident. Ultimately separated from his parents within the workhouse, Crooks witnessed things that shaped his adult life. In 1866, he saw the bread riots, where hungry men mobbed the baker’s wagon as it made deliveries. Before the wagon was even on the grounds, the fighting began, with men grabbing bread and eating it where they stood. Crooks’s mother managed to pay for the boy’s schooling, leading Crooks to become one of the leaders of the dockworkers’ unions. From there, he was elected to London City Council, turning his attention to those who still languished in the conditions he had left behind. He introduced some groundbreaking ideas that gave impoverished children the same chances he had. For one thing, they were now sent to local schools instead of being forced to labor alongside their parents. He also overturned a law that, in retrospect, was unthinkable. The masters in charge of a workhouse had the legal right to turn away any government officials that showed up for unannounced inspections, effectively leaving masters unaccountable for their actions. In the late 1800s, Crooks became the first working-class man appointed to the Poplar Board of Guardians, helping to improve the conditions and food. Crooks also tackled the problem of inadequate clothing for workhouse residents, identifying laundry services that refused to wash clothes because they were filled with bugs and vermin. He recounted the story of one woman who scrubbed floors every day with only a pair of cloth sacks to protect her feet.

5 The Huddersfield Workhouse Scandal

Beginning in 1846, a typhus outbreak opened the doors of the Huddersfield Workhouse to public scrutiny. During the outbreak, the workhouse was overwhelmed with sick people, placing about three patients in each bed. Many were moved to other facilities. The outbreak lasted from 1846 to 1847. In 1848, the Leeds Mercury headed into the workhouse to write an expose on what they found. They reported that it was absolutely unfit for human habitation, even though it was one of the best workhouses in the area. Another report revealed that typhus patients were being treated on bags of lice-ridden straw instead of beds. Each room housed up to 40 children, with anywhere from 4 to 10 forced to share a single bed. During the typhus epidemic, the workhouse was filthy, with overflowing sewage systems and children who scratched themselves raw from the bugs. Shockingly, an 1857 special committee found much the same conditions. They reported that “abandoned women” sick with disease were living alongside young children. In addition, there was no separation between those suffering from infections and contagious diseases and women giving birth. There were even cases of the living languishing alongside the dead. Conditions were so unsanitary that the pots used for cooking were also used to wash soiled linens and bedclothes. There were no qualified nurses to treat the patients. Many of those who were dispensing medications couldn’t even read the labels on the bottles. Ultimately, it took much longer to clean up the workhouse than expected. By 1870, Huddersfield was still well behind other workhouses in providing better care for their residents.

4 Ella Gillespie

Children were among the primary targets for cold, uncaring workhouse personnel. In 1894, 54-year-old Ella Gillespie, a former nurse and overseer at Hackney Union’s Brentwood schools, stood trial on charges of neglect and abuse of the children in her care. For approximately eight years, Gillespie was in charge of about 500 children. As those children came forward to testify against her, the entire country was horrified by the scandal. Punishments and abuses were severe, bordering on bizarre. A common punishment was the “basket drill,” where children in nightclothes paraded around their rooms for hours while balancing their daytime clothes in baskets on their heads. Talking to other children was punishable by having their heads slammed against the wall. There were also spur-of-the-moment blows with hands or frying pans. Children were often sent to fetch stinging nettles before being beaten with them. In addition, water was often withheld, forcing children to drink from puddles outside or toilets inside. Others testified that Gillespie was regularly drunk, avoiding detection of her crimes during surprise inspections by meeting inspectors outside the school and treating them to lunch first. Gillespie was found guilty, receiving five years’ penal servitude as her punishment.

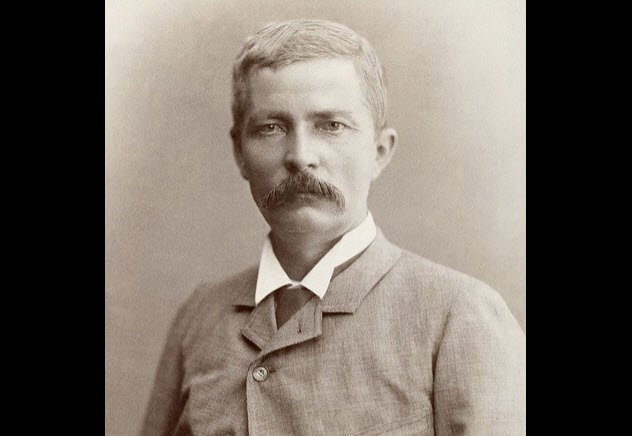

3 Henry Morton Stanley

In 1847, John Rowlands entered the St. Asaph workhouse in Flintshire. An orphan, he grew up to become Henry Morton Stanley, a reporter for the New York Herald who is still remembered for his famous question, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” In his youth, he was left at a workhouse by foster parents after his uncles refused to pay for his upkeep. Stanley talked about his workhouse experiences in his autobiography, recalling the intimidating iron gates, the endless tasks, and the injustice. “To the aged it is a house of slow death,” he wrote, “to the young it is a house of torture.” When Stanley was confined to the workhouse, it was ruled by schoolmaster James Francis, who was renowned for his cruelty. Stanley discovered just how far Francis would go when classmate Willie Roberts died. After Roberts’s death, Stanley sneaked into the workhouse morgue to find the body, clearly bearing the marks from his fatal beating. Shortly afterward, the headmaster threatened to beat the entire class because of some marks on the surface of a new table. When it was Stanley’s turn, he fought back, getting pummeled but still managing to kick Francis in the face. Then, grabbing a blackthorn, Stanley beat the schoolmaster bloody. Fearing the consequences, Stanley fled the workhouse and headed to the freedom of the ocean.

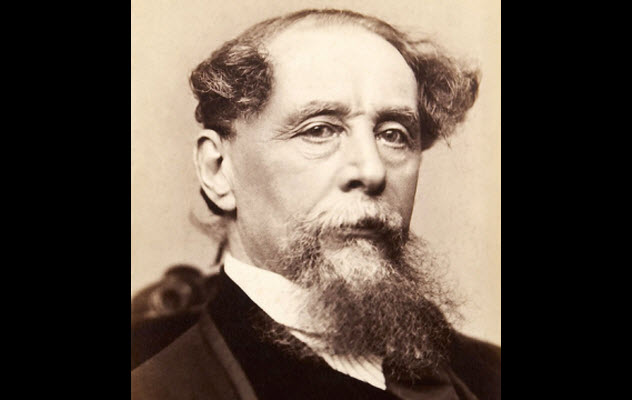

2 The Tooting Tragedy And Charles Dickens

A famous supporter of the rights of the poor and the lower class, Charles Dickens was outraged by “The Tooting Tragedy.” In 1849, a cholera epidemic swept through Bartholomew Drouet’s farming workhouse facility. At the time, it was home to around 1,300 boys and girls. Although Drouet received an allowance to make sure they were kept properly, the children were sallow, underweight, and starving. In January of that year, 150 children died from cholera. Investigators found that Drouet wasn’t caring properly for either the healthy or the sick children. In fact, he had ignored all of the Board of Health recommendations for keeping illness and disease from causing unnecessary harm to the children. When the first fevers developed and it was recommended that all the healthy children be taken from the home, Drouet refused. Ultimately, he was found guilty of manslaughter and negligence. Dickens used the case to illustrate the kind of horrible conditions in which children were living. After writing a handful of articles, Dickens became an outspoken representative of the Metropolitan Sanitary Association, arguing for reform in the sanitation and healthcare of workhouses. He also pointed the finger at people who were getting in the way of change. By 1850, Dickens had his own journal, Household Words, and his own platform for both sanitation and housing reform. He was determined to speak for the children who had no voice of their own.

1 The Guardians’ Lunch

Although far from a perfect arrangement, a group of guardians were supposed to oversee workhouse conditions. Instead, these guardians became the perfect example of what was wrong with the workhouse system. In March 1897, scandal hit London when one of the City of London Union Guardians moved to discontinue the group’s habit of dining at the workhouses after their meetings. It was soon revealed just what the guardians of the poor and the destitute were dining on during their board meetings. Worst of all, the motion was defeated. Each meal started with bread, cheese, beer, and liquor. After the meeting, which lasted about an hour and a half, there was fish, beef, roast mutton, various birds, puddings, and sweets. That was followed by a series of toasts with champagne and fine wines. Copious amounts were consumed as the men toasted everyone from the queen to the youngest member of the board. Worst of all, it was all done with workhouse inmates laboring outside the window. Their gluttony was even more outrageous when compared to the meager offerings in the workhouses. When 66-year-old Honor Shawyer died from “mortification of the bowels” in the Droxford, Hampshire, workhouse, an investigation revealed that the inmates were routinely neglected, denied needed medical care, and given meals that were below the already substandard requirements of the workhouse. Instead of serving soup to the inmates, the kitchen was serving pork-water, which is exactly what it sounds like. Their puddings were made with the gunk skimmed off the top of the pork-water. The Guardians intervened, insisting that the inmates be given soup made with real meat. That didn’t last long, though. When the Guardians failed to confirm that their rules had been implemented, pork-water returned to the menu. Read More: Twitter