10 Cincinnati Riots Of 1829

The Cincinnati riots of 1829 were some of the earliest incidents of racial violence against immigrants in the US. These riots were mostly incited by white Irish immigrants in Ohio who felt threatened by the influx of African-American settlers. Ohio was a free state when it became part of the US. That made it a refuge for African Americans who had escaped slavery or were trying to make a life in the West. During the mid-1820s, the African-American population in Cincinnati increased dramatically from 700 to close to 3,000, which concerned many white settlers. The most fearful group was made up of poor, white laborers, who believed that the uneducated former slaves would force them out of jobs. Most of these white laborers were Irish immigrants. Tensions reached their peak in August 1829 when 300 white people attacked African-American neighborhoods to drive the residents out of Cincinnati. At first, African-American community leaders advocated staying in Cincinnati to stand up for their rights. But the violence was too intense, and many African Americans decided to head north. Their goal was to find a safe haven in Canada. A few thousand did make it across the border and settled in Canada. The exodus even led to black towns forming in Ontario. However, a good number of African-American citizens stayed in Cincinnati and suffered from the racial tensions for decades.

9 Greek Town Riot

Anti-immigrant sentiment is not new to the US. Most people around the world have heard of historic Irish discrimination or the American debate on Mexican immigration. But less well-known is the anti-Greek sentiment that fomented violence in the US during the early 20th century. One of the more shocking incidents was a riot in Nebraska in 1909. It started when a police officer arrested a young Greek immigrant. The Greek man pulled out his pistol and shot the officer during the arrest. This inflamed racial hatred against the Greeks, with Nebraska newspapers calling the Greeks a menace to the American working class. Tensions reached a peak on February 21, 1909, when a mob of 3,000 men attacked the Greek settlement in South Omaha known as “Greek Town.” Mob members indiscriminately attacked Greek houses, beating men, women, and children alike. One Greek boy died during the attacks, and community leaders asked the government of Omaha to help them quell the mob. Help did not come, so the Greek community made a mass exodus from South Omaha. Within a few weeks, there were no Greeks left in the city.

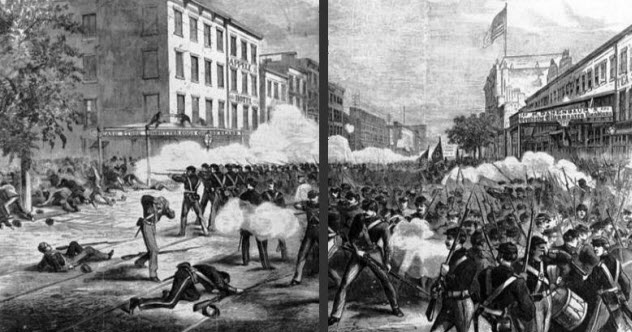

8 Orange Riots

In the 19th century, one of the most deadly but forgotten incidents of racial violence in New York was the “Orange Riots.” Tensions between Irish Protestants (aka Orangemen) and Irish Catholics were common during this time and resulted in the deaths of eight people during a holiday march in 1870. When the Orangemen asked permission to march again in 1871, New York officials banned the parade. This caused discontent among the Irish Protestants, who complained continuously to government officials. Eventually, the officials gave the Orangemen permission to hold a parade but under protection of the National Guard. On the day of the parade, the Orangemen marched while surrounded by infantrymen. Even so, the streets were filled with Irish Catholics. Immediately, the Catholics began attacking the Protestants and the National Guard with gunfire and rocks. The National Guard responded by shooting their muskets into the crowd and bayoneting rioters. Still, the parade continued. Without permission, the police fired into the crowd and even started a cavalry charge. When the riot ended, 60 people were dead and 150 people were injured.

7 Camden Riots Of 1971

In 1971, police in Camden, New Jersey, pulled over Hispanic motorist Rafael Gonzales for a routine traffic stop. During the arrest, the police officer responsible for the traffic stop felt threatened by Gonzales and beat him to death. Public fury ignited into riots when the police officer was not charged with any wrongdoing. Hispanic residents took to the streets to demand action against the officer. Although Camden officials gave in and charged the officer, they let him stay on the job and did not really punish him. Outraged, Camden Hispanics took to the streets again on August 20, 1971. For three days, the city was under siege. Rioters looted stores and destroyed buildings, prompting the police to get involved. However, a lack of cohesion in the police force led to multiple incidents of police violence. The streets of Camden were filled with tear gas and officers firing their weapons. In the end, police arrested 90 people. The officer responsible for the death of Rafael Gonzalez was finally suspended from his job. Although forgotten by or unknown to most people, these riots bear similarities to the Baltimore riots in 2015. Forty-five years later, it appears that America still has serious issues with police brutality.

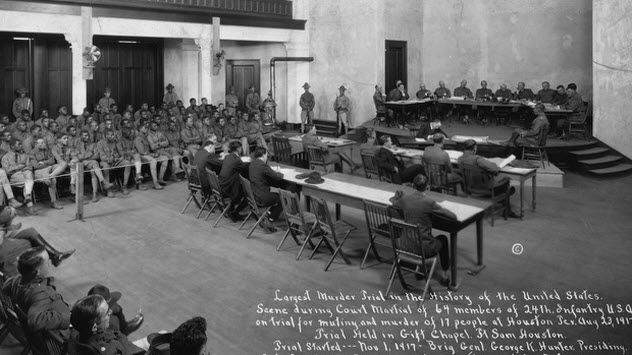

6 Houston Riot Of 1917

When the US entered World War I in 1917, the US armed forces—including the Third Battalion of the 24th Infantry Regiment—began training for the conflict. This battalion was exclusively for African-American soldiers. At first, they trained in New Mexico. But they were soon transferred to Houston, Texas. Having African-American soldiers in this heavily segregated Southern city caused problems between the soldiers and the white community. Not used to the strict segregation, many of the soldiers chafed at their treatment by white residents. Tensions came to a head when the Houston police violently arrested an African-American woman in the area. Battalion soldiers became involved in protecting the woman. When violence ensued, the police shot one of the African-American soldiers three times but did not kill him. Word got back to the battalion about the incident, and tensions increased. Knowing that a riot was imminent, the commanding officers of the regiment ordered all men to turn in their weapons. Instead, the soldiers of the battalion raided their camp of all weapons and marched into town. Once there, the battalion exchanged gunfire with police officers and fired at civilian buildings occupied by white residents. The gun battle lasted throughout the night. In the end, 19 people died of gunshot wounds. Houston imposed martial law, and the leaders of the battalion were court-martialed in the largest such trial in US history. Their defense highlighted the racism they faced, but the tribunal was not convinced. Nineteen men received death sentences and were hanged. Sixty-three others received sentences of life in prison.

5 Thibodaux Massacre

In 1887, Thibodaux, Louisiana, experienced a three-week labor strike from local sugarcane workers. The protesters organized a force of a few thousand people, most of whom were African American. Early attempts to end the strike failed. Strikers demanded increased wages and more consistent pay periods. They also demanded that payment be in actual US currency. Back then, companies paid their workers with special tickets that could only be redeemed at company stores. Both sides refused to budge. In the late 19th century, most labor strikes ended in violent shows of force, and this one was no different. Taylor Beattie, a state judge who had once owned slaves, put Thibodaux under martial law and declared that African-American residents could not leave the city without special passes. A vigilante group formed, which boxed in the strikers in Thibodaux. When the strikers fired on the vigilante group and killed two of them, mass violence began. For three days, the vigilantes attacked the strikers and their families, executing them on the spot or in the nearby woods. According to official numbers, 35 people died. But citizens kept discovering bodies for some time after the strike ended, prompting historians to estimate casualties at 300. The massacre also had a racial element. Every single one of the dead strikers was African American, and nearly all of the vigilantes were white.

4 Agana Race Riot

When the US took Guam during World War II, Americans quickly began building airstrips for B-29 Superfortress bombers. The US intended to use the island as a base from which to launch bombing raids on Japan. Soon Guam became a staging area for operations all over the Pacific theater. Soldiers, ships, and airplanes constantly traveled through Guam. However, the effectiveness of the island was marred by a race riot that happened over Christmas in 1944. Trouble started when the African-American Marine 25th Depot Company arrived on Guam and was stationed near the major city of Agana. Distrustful of the African-American Marines, white Marines tried to prevent them from entering the city, especially if they were looking for women. For months, tensions increased. Then, right before Christmas, a white Marine fatally shot an African-American Marine in a quarrel over a local woman. Although the white Marine was court-martialed, the African-American Marines were still outraged. On Christmas Eve, a group of nine African-American Marines used their leave passes to visit Agana. When they got into the city, white Marines opened fire on them. Eight of the African-American Marines made it back to base, but one got left in the city. Rumors circulated that he was dead, so 40 African-American Marines stole some trucks and drove into the city. Alerted to the incoming trucks, the military police set up roadblocks. When the Marines showed up, the MPs told them that the missing man was safe. The African-American Marines returned to base. But even though they hadn’t engaged in violence, their barracks were attacked by white Marines in retaliation for what the African Americans had planned to do. This led to firefights throughout Christmas Day. White Marines killed some enlisted men in the African-American camps. Eventually, the attacks stopped, and many of the people responsible for the violence received court-martials.

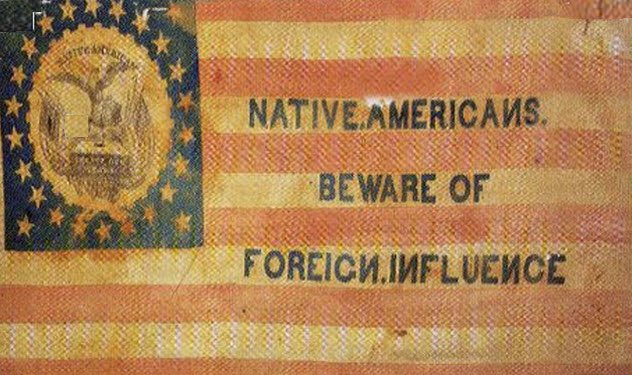

3 Bloody Monday

In the mid-19th century, the US Whig Party shattered into a variety of extremist parties. One of the most well-known was the Know-Nothing Party, a radical anti-immigrant party that spread inflammatory rhetoric against any foreigner trying to move into the US. In Louisville, Kentucky, the rhetoric focused on German and Irish immigrants. During the August 1855 election, leaders of the Know-Nothing Party organized to “protect the polls,” threatening violence against immigrants to keep them from voting. Throughout the day, violent threats escalated until the Know-Nothings began to attack the immigrants. Mob leaders shot at immigrants and raided their houses and stores, breaking windows and stealing products. Gun battles erupted across Louisville, with some Irish immigrants fighting back against the Know-Nothings. Rioters set Irish houses on fire in retaliation. Eventually, the Louisville mayor, who belonged to the Know-Nothing Party, got the violence under control and ended the riots. Twenty-two people had died, but local judges did not charge any rioters with crimes. The Louisville city government also refused to compensate the immigrants for property damage. Recently, Louisville erected a monument to honor those who died in the senseless violence.

2 Crown Heights Riot

The Crown Heights riot of 1991 started in Brooklyn when a Jewish man named Yosef Lifsh was driving in a rabbinic motorcade. During the drive, he crashed his car into two African-American children. African-American residents attacked Lifsh and his passengers, beating them severely. When a Hasidic ambulance service arrived, the police ordered them to get the Hasidic men out of there. Later, one of the African-American children died as a result of the crash, creating more anger in Crown Heights. Black residents believed a false rumor that the police and EMTs had prioritized care to Lifsh because he was Jewish. African-American residents in Crown Heights were already distrustful of the increasing Jewish population, and the crash only fueled their anti-Semitism. On August 20, 1991, rioting began against the Jewish residents. Within three hours, rioters had killed a Jewish man. For three days, the riots raged with African-Americans and Caribbean-Americans attacking Jewish houses and stores. People who did not even live in Crown Heights came to take part in the violence. Among the rioters was Reverend Al Sharpton, who spread anti-Semitic propaganda and organized marches during the riots. Police officers swarmed the area and finally took control of the situation after three days. They made hundreds of arrests, but many Jewish stores and residential areas suffered damage. Even so, most Jews in Crown Heights did not relocate, and race relations between Jews and African-Americans significantly improved right after the riots. The riots remain one of the worst acts of anti-Semitism in US history.

1 1921 Tulsa Race Riot

After World War I, racial tensions in Tulsa, Oklahoma, reached a peak. For years, the city had strict Jim Crow laws that segregated African Americans and made them second-class citizens. World War I also created profound economic and social changes in the city, especially as soldiers came back from their horrific experiences overseas. In 1921, this tension came to a head when a rumor spread that Dick Rowland, an African American who shined shoes for a living, had sexually assaulted a white elevator operator. On May 31, police arrested Rowland. Quickly, more rumors spread about a possible lynching by white vigilantes. That night, a white group stormed the courthouse and demanded that Rowland be handed over to them. A group of armed African Americans arrived to try to stop the lynching. But when the first gunshot was fired, the African Americans fled back to their neighborhood. With the support of the Tulsa police chief, a white mob formed, took up arms, and chased the African Americans. The rioting that followed destroyed about 40 city blocks in the part of Tulsa where African Americans lived. African Americans also suffered most of the 100–300 deaths and the approximately 800 injuries that happened that night and the following day. There were no criminal convictions for the perpetrators of this violence, and no one was compensated for their losses. The charges against Dick Rowland were dropped after the riots. Zachery Brasier is a physics major who likes to write on the side. Check out his blog at zacherybrasier.com.