People love to laugh, and some scientists love to study it. Why not? It’s a fascinating subject. It’s frequently touted as the best medicine, yet there exists a wealth of anecdotal accounts of people dying while doing it. Collected here are but a few examples of scientists’ findings on one of life’s more pleasant activities. SEE ALSO: 10 Things That Will Make You Die Laughing

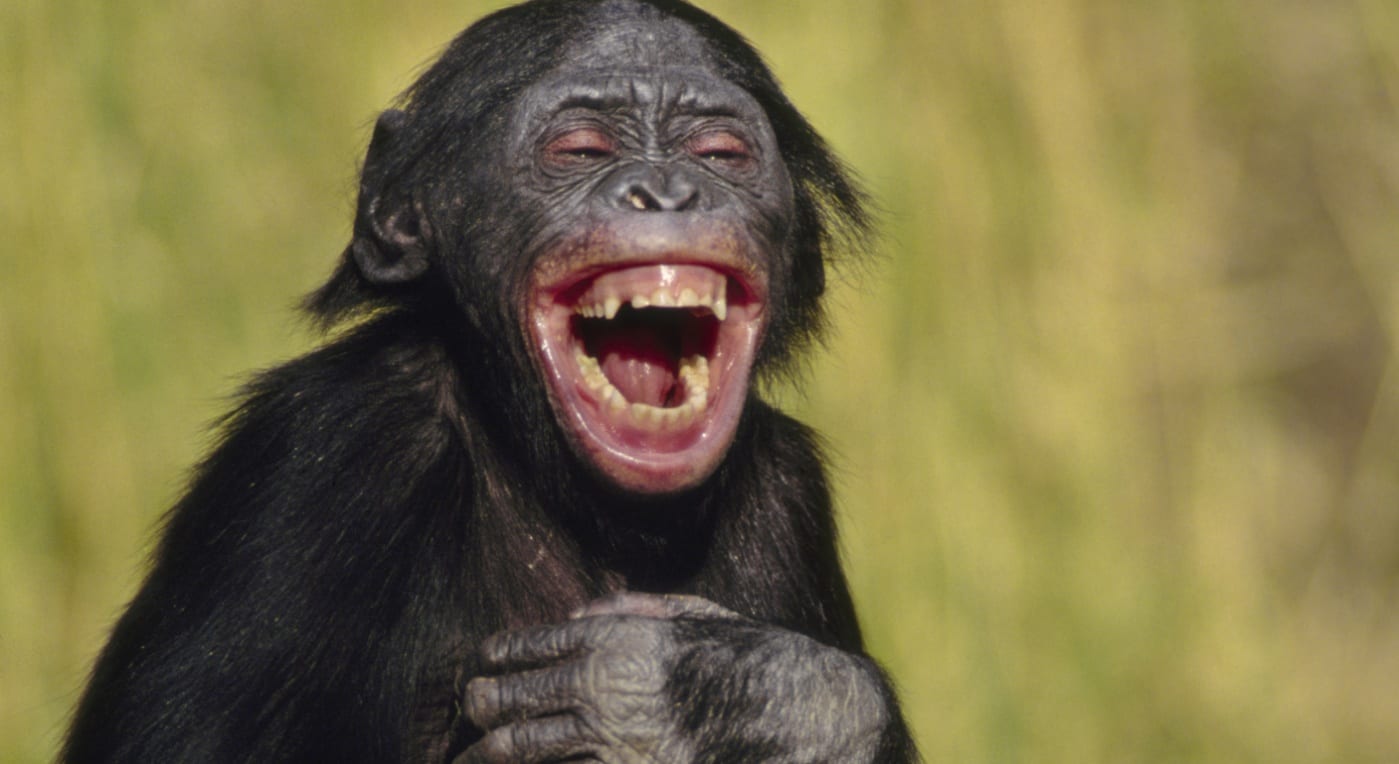

10 Babies and Chimps

Fact: Babies Laugh Like Chimps Chimpanzees are considered to be our closest living relatives, so of course humans and chimps have much in common. According to a 2018 study, we can add how we laugh to that list, at least where infants are concerned. A trio of psychologists and a phonetician from various European universities studied the laughter of 44 babies, aged between three and 18 months. To accomplish this, they simply collected suitable video clips of babies laughing, of which there is no shortage on the Internet. Of particular interest was how much of the laugh was produced during inhalation versus exhalation. A convenient group of 102 psychology students evaluated the clips in this respect. Results indicated that younger babies laughed both while inhaling and exhaling, as is seen in chimpanzees. Babies at the older end of the study’s age spectrum tended to laugh primarily during exhalation, as human adults mostly do. This shift in the manner of laughter wasn’t tied to any specific developmental milestones but rather appeared to come gradually with additional months of age. The researchers admitted that these determinations were made by nonexpert listeners but planned to have other phoneticians judge the clips as well. According to Dr. Disa Sauter, leader of the study, there is no agreed-upon reason why humans mainly laugh on exhalation while other primates don’t. It may be due to the superior vocal control of humans. Further avenues of research include whether the inhalation/exhalation ratio of laughter is linked with the cause of said laughter (something that also tends to change as babies grow older) as well as if similar breathing changes are seen in other types of vocalizations.[1]

9 Fake Laughter

Fact: We Can Spot Fake Laughter, No Matter Where We’re From Sometimes you laugh because someone told a side-splitter that leaves you in tears, and sometimes you laugh just to be polite. Whether to butter up one’s boss or as a segue into civilly excusing oneself from a sandpaper-on-eyeballs terrible conversation, plenty of us have sputtered out a charitable chortle here and there. Unfortunately, these fake laughs may not be fooling anyone. In 2018, Dr. Greg Bryant of UCLA published research indicating that the ability to recognize genuine laughter is present across cultures. Bryant and his co-authors tested this on 884 people from 21 countries across six continents. The participants listened to recordings of laughs, both spontaneous laughter recorded from English-language conversations and volitional laughs from those asked to do so on command. Regardless of their society of origin, listeners were able to tell real laughs from fake ones at a rate better than chance. At the low end, Samoans correctly identified the laughs 56 percent of the time, and at the high end, Japanese listeners were right 69 percent of the time. Dr. Bryant also noted that fake and real laughter do have different sonic qualities, with fake laughter essentially sounding a bit more like speech than real laughter.[2]

8 Canned Laughter

Fact: Canned Laughter Works Speaking of fake laughter, consider the laugh tracks in sitcoms. They may not be as prevalent as they once were, but they’re hardly relegated to the land of syndicated reruns. These days, critics wish these laugh recordings would indeed die. The problem is that canned laughter might just help to make things seem funnier. In 2019, Current Biology included a study by Dr. Sophie Scott of University College London which examined the effects of recorded laugh tracks on those insidious boogeymen of comedy: dad jokes. Here are four examples which were employed in the study: What state has the smallest drinks? Mini-soda! What does a dinosaur use to pay the bills? Tyrannosaurus cheques! What’s orange and sounds like a parrot? A carrot! What do you call a man with a spade on his head? Dug! As you can see, these are not good jokes. Seventy-two unfortunate souls were presented a total of 40 such jokes, followed either by no laughter, fake laughter, or genuine laughter. The participant then rated how funny the jokes were on a scale of one to seven. Results showed that the addition of laughter had an effect; the ratings increased by about ten percent with fake laughter and by 15 to 20 percent for real laughter.[3]

7 Immunity

Fact: Laughter And The Immune System A 2003 study examined the effects of laughter on the activity of natural killer cells (aka NK cells), which play an important role in the immune system. The researchers recruited 33 healthy adult women from rural areas in the Midwest. Those in the experimental group were shown a comedic video, while those in the control group were shown a tourism video. Women in the experimental group were given a choice of watching a stand-up segment by Bill Cosby, Tim Allen, or Robin Williams. Most chose Cosby. (It was 2003.) How funny they found the videos was assessed by an observer using the Humor Response Scale (HRS), developed for the study. Afterward, both the experimental and control groups’ NK cell activity was assessed. The experiment showed that simply viewing a comedic video did not result in a statistically significant increase in NK cell activity. However, the HRS scores of women in the comedy group did how a statistically significant positive correlation with NK cell activity. The increase was especially pronounced for those whose HRS scores were 25 or higher. On the other hand, women who saw a comedic video but didn’t find it funny actually had reduced NK cell activity.[4]

6 Dominance

Fact: Dominance And Laughter Research by Dr. Christopher Oveis of UC San Diego has shown that higher-status individuals tend to laugh differently than those with less power, and people pick up on those cues. In 2014, he set out to confirm that status can affect how people laugh. Previous research had already indicated that being in a position of power can affect acoustic aspects of speech. This time, videos of four fraternity brothers (two new ones and two who’d been with the frat for at least two years) were shown to various teams of observers who didn’t know what the study was investigating. In the videos, each brother took turns being teased by the other three. Their laughter was rated by how dominant it sounded and also assessed for attributes like loudness and pitch. Dominant laughter was shown to be louder and higher-pitched and also more variable in tone. The new pledges only showed dominant laughter when they got to do the teasing, whereas the long-running fraternity brothers showed dominant laughter at all times. A second study in 2016 saw 51 students listening to 20 recordings of the fraternity members’ laughs. They were asked to rate the social status of the laugher. As you might expect, dominant-sounding laughers were seen as higher in status. This was even true when the dominant laugh came from one of the new pledges, implying that perhaps one can appear to be in a position of power by laughing in a certain way. At the same point, even if a submissive-sounding laugh was made by an established frat boy, it was perceived as coming from a high-status individual.[5]

5 Psychopathy

Fact: Is Immunity To Laughter A Warning Sign Of Psychopathy? Quite a bit of research has gone into which childhood behaviors may predict psychopathy in adulthood, and that includes laughter. You’ve probably heard laughter described as contagious, and research has even shown that simply hearing laughter will spur the brain to prepare the facial muscles for laughing. As it turns out, boys at risk of psychopathy in adulthood may be immune to the giggling pandemic. In 2017, researchers at University College London recruited a sample of 92 boys between 11 and 16 years old, 30 “normal” kids as a control group and 62 who showed possible indicators of eventual psychopathy. All 62 displayed disruptive behaviors but were further divided based on whether or not they also displayed “callous-unemotional traits.” The boys were given MRIs while listening to recordings of genuine laughter, fake laughter, and crying sounds. The participants were also asked to rate how much each sound made them want to feel that emotion. The MRIs showed that all the boys’ brains responded to the sound of genuine laughter. However, those with both disruptive behaviors and callous-unemotional traits showed less activity in the supplementary motor area and anterior insula, brain regions associated with joining in laughter and feeling others’ emotions. This difference was also present in boys who were disruptive but not callous-unemotional, albeit to a lesser extent. Study leader Dr. Essi Viding noted that it’s hard to say whether the diminished response to laughter is caused by the boys’ behaviors or is a consequence of it but that the findings absolutely warranted further research.[6]

4 Appetite

Fact: Laughter And Appetite In 2010, Dr. Lee S. Berk, Dr. Jerry Petrofsky, and others conducted a study on how “mirthful laughter” (a form of eustress) affected the levels of hormones that modulate appetite. Any such effects were compared with what happens when a subject is distressed. Fourteen participants were shown a comedic video of their choice for the eustress half of the experiment and the first 20 minutes of Saving Private Ryan for distress. In this case, everyone viewed both the funny and upsetting videos, spaced a week apart. For each segment, subjects had their blood pressure taken and blood drawn both before and after the videos. Viewing the distressing video caused no statistically significant change in appetite hormone levels and presumably made no one hungry. Watching a funny video, however, led to a decrease in leptin and an increase in ghrelin, something that is also seen after moderate exercise. Dr. Berk pointed out that the study did not simply conclude that laughter makes you hungry (not that this stopped several news outlets from reporting it as such). However, the findings were valuable for their implications when it comes to treating patients unable to use exercise to increase their appetites.[7]

3 The Best medicine

Fact: Making The Patient Laugh, Literally A study published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation in 2019 indicated that electrically stimulating a certain part of the brain could reliably induce laughter as well as reduce anxiety. While stimulation of other brain areas has been shown to cause laughter, this is reportedly the first time that a reduction in anxiety was also observed. A research team was performing electrical stimulation brain mapping on epilepsy patients. This is a procedure wherein electrodes are placed on the brain in order to stimulate various regions. Doing so can provide insight into the source of seizures. While working with a 23-year-old woman, the researchers found that stimulation of her cingulum bundle consistently caused uncontrollable laughter, smiling, and feelings of calm and relaxation. Her mood was elevated, and her cognitive abilities were not impaired by the simulation. After observing this, the team tried the same thing on two more patients and got the same results. Study co-author Dr. Jon T. Willie postulated that this effect was due to the cingulum bundle’s connections with other parts of the brain, including those associated with emotion regulation. This finding carries a myriad of treatment implications. First and foremost, it could be a means of easing the experience of brain surgery during which the patient must remain awake. This technique may one day lead to treatments for depression, anxiety, and chronic pain. For the moment, a medicinal shock to the cingulum bundle requires invasive surgery, but advances in medical technology down the road could provide a less invasive form of administration.[8]

2 The Laughie

Fact: The Laughie . . . is it the new selfie? Love it or hate it, the selfie is here to stay. Scores of people around the world are snapping them with their smartphones and uploading them to social media, to the enjoyment or chagrin of their peers. To some, selfies are a sign of societal decline; to others, they’re a form of self-affirmation and even therapeutic. But what about the Laughie? In another study published in 2019, Freda Gonot Schoupinsky, a graduate student at the University of Derby working under the supervision of Dr. Gulcan Garip, was examining the effect of laughter on well-being. Specifically, this research involved the Laughie, a smartphone recording of one’s own joyous laughter to be listened to when desired. Twenty-one participants between the ages of 25 and 93 created their own minute-long Laughies and played them back three times a day for a week. In 89 percent of these sessions, participants ended up laughing for most of the playback. Nineteen of them reported increased well-being after the week was up. Their scores on the World Health Organization Well-Being Index were 16 percent higher, and those whose scores weren’t very high beforehand benefitted the most. It seems that laughter is contagious even when it’s your own.[9]

1 Risible Rats

Fact: Rats laugh Laughter is not unique to humans, as already implied by the comparison of babies’ laughter to that of chimpanzees above. Another animal in which laughter has been observed may come as more of a surprise: rats. According to a study in 2000, rats, when tickled, emitted the same sounds they would when playing. (These sounds are typically outside of the human auditory range.) Some rats really liked being tickled, too, to the point that they’d follow the hand of the scientist who tickled them. In a 2016 study, researchers at Berlin’s Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience also tickled rats. They tested the rodents’ reaction to vigorous tickling, gentler tickling, and a chase game. The chase game and vigorous tickling caused the rats to make their happy giggling sounds. Through the use of electrodes, it was shown that all three activities promoted increased activity in the somatosensory cortices of the rats’ brains. Electrical stimulation of this region also caused the rats to laugh, though it’s unknown if the rats were actually enjoying said stimulation. Notably, if the rats were made anxious (in this case by being put on a high pedestal under bright lights), both the happy vocalizations and the somatosensory cortex activity in response to tickling were noticeably lessened. This was taken as confirmation that the rats’ giggling and brain activity during the previous conditions weren’t actually signs of alarm.[10]