10 The Israeli Complex

On the banks of Nahal Guvrin sits the ghostly traces of Canaanite worship. The site of Tel Burna produced scorched animal bones and sacrificial artifacts, prompting Israeli archaeologists to credit the 3,300-year-old temple complex to a cult. The vast site was used as their home and religious center. Since there is no neon sign with the honored god’s name, experts are casting their vote for either the Canaanite storm god Baal or war goddess Anat. However, it’s more likely that the flourishing community revolved around Baal adoration. Not a lot is clear about the cult’s everyday life, but other items found at the site indicate a people who traded technology and cultural influences with other civilizations, including Egypt and Cyprus.

9 Dumpster Deity

When a severed head was found in County Durham, it thankfully wasn’t the start of a murder mystery. A first-year archaeology student found the 1,800-year-old stone carving while digging at Binchester Roman Fort. Made from sandstone, the stone head intrigued researchers with its looks. A mix of classical Roman and local Romano-British styles, its features fit those of a Celtic god called Antenociticus. The head was discovered near another religious artifact, a Roman altar unearthed two years earlier. In fact, they might have been part of the same shrine. It would appear that the deity lost its following when the building fell out of favor around the fourth century AD. The 20-centimeter (8 in) head was dumped and forgotten. His real story remains as lost as the rest of his body, but archaeologists feel this is most likely the regional war god Antenociticus.

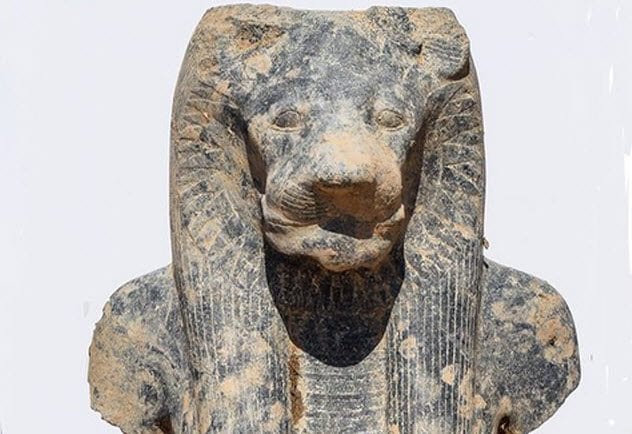

8 The Sekhmet Collection

In the Egyptian pantheon, the goddess Sekhmet was bodyguard to the pharaohs. She was fierce and feminine at the same time—always shown as a lithe woman with a lion’s head. At the Temple of Amenhotep III, once the biggest mortuary center around Thebes, eight statues of Sekhmet were discovered. Made from black granite, two show the feline goddess standing upright and the rest seated on a throne. Sadly, only three are partially intact. The standing Sekhmets are merely torsos holding sacred artifacts such as the papyrus scepter and ankh. Each throned figure also clasps the symbol of life in her right hand. Found with them was another headless (and limb-lacking) piece of black granite. Archaeologists determined that it was once a statue of Amenhotep III, the 13th-century BC pharaoh who took Egypt to the height of its power.

7 The Brand-New God

An unknown god defies identification. Discovered on an ancient wall in Turkey, he has no equal. The relief figure, shown rising between leaves, seems to be a complex hybrid. The site’s 2,000-year-old religious history is as mixed as the mutant god. A sacred Iron Age building was later adapted by worshipers of Jupiter Dolichenus, another hybrid but known god. During the Middle Ages, a Christian monastery took over and sealed the basalt relief into a wall. When it was rediscovered, symbols surrounding the god deepened the confusing anonymity. Two symbols have associations with other gods—the rosette with the Mesopotamian god Ishtar and the crescent Moon with the lunar god Sin. The unknown god’s beard denotes Roman influence, but the scene’s design is somehow Iron Age. Unless another image of this mystery man is found along with some tangible information, his name will never be known.

6 A God’s Grave

In the 1880s, archaeologist Philippe Virey became the first to set foot in a tomb located in Luxor, Egypt. While it was an impressive find, nobody guessed the real reason behind its construction. Recently, when excavations revealed additional chambers, the amazing truth come out—it was the tomb of the Egyptian god Osiris. Unfortunately, there was no holy corpse because the site was merely symbolic. No deceased deity would ever rest there in peace, but the builders didn’t skimp on grandeur. To honor the judge and ruler of the underworld, Osiris’s tomb was designed as a royal one. There are many shafts and chambers, some richly decorated while others still wait to reveal their contents. There is also a large hall supported by five pillars with a staircase leading down to a complex with a carving of Osiris.

5 Love At Petra

Next to another staircase, Aphrodite awaited discovery. Researchers exploring the ancient desert city of Petra found a pair of statues beautifully crafted from marble. Both show the goddess of love in good condition, and one even has a tiny Cupid at her feet. The two Aphrodites were a complete surprise. Digging took place in an area thought to be a lower-class home, but it turned out to be a first-century luxury villa. The Nabataeans, the culture that built the stone city, habitually incorporated influences from other nations. When the Romans invaded Nabataea in AD 106, the locals appeared to have adopted their queen of hearts as well. The figures still have some of their original paint and were sculpted in the second century AD. They provide a fresh view on how Roman occupation influenced Nabataean art and perhaps worship.

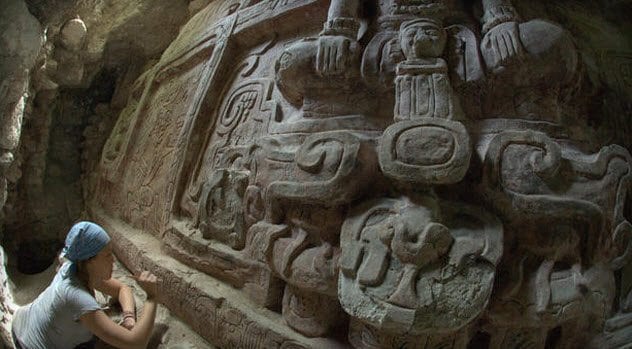

4 The Mayan Frieze

Tomb robbers just missed a large treasure when they tunneled underneath a pyramid in Guatemala. It wasn’t a chest stuffed with precious jewels but a stretch of stone. Measuring 8 meters (26 ft) by 2 meters (6 ft), the elaborate wall sculpture is packed with images of Mayan gods and deified rulers busy with a crowning ceremony. Even though it was created 2,000 years ago, the artwork is well-preserved and pigments of red, blue, yellow, and green still survive. It’s a happy find for archaeologists. At the bottom of the rare relief, an inscription states that the building was erected by King Ajwosaj, a notable leader in Mayan history. The discovery of the frieze reveals how far-reaching the royal’s political and religious power really was and how he claimed to have restored the gods to their rightful place.

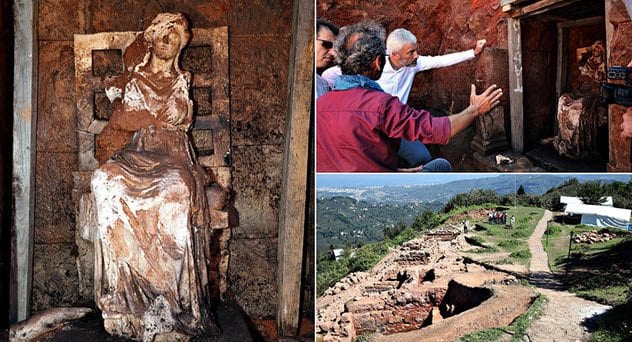

3 Cybele

In Turkey, a priceless statue weighing a whopping 200 kilograms (440 lb) was found in the ruins of a fort. Known as Cybele, the mother goddess of Anatolia, she’s shown as a pregnant woman sitting on a throne. Unlike many old statues—and this one is around 2,100 years old—she’s nearly undamaged. Her presence indicates that the fortress of Kurul was once a site of importance, which was probably why it suffered a particularly brutal Roman assault. On that day, the entrance walls caved in on Cybele. But instead of crushing the sculpture, it entombed her safely until she was rediscovered. Ironically, the goddess is associated with walls. She’s also a fertility deity connected to mountains and wild animals. The marble creation is the first ancient statue in Turkey’s history to be discovered in its original position.

2 Uni And Tina

The culture of the Etruscans is lost. Since they recorded the written word mostly on perishable wax and linen, little is known about them. But a dig in Tuscany gave researchers a much-needed break. One of the longest inscriptions of the Etruscans’ extinct language was identified on a sandstone stele. Experts deciphered two names—Uni, their fertility goddess, and Tina, their main god. The temple site, Poggio Colla, previously yielded the oldest birth art in Europe. Now that Uni’s name has come up, it’s likely that a fertility cult worshiped the goddess there. If true, it’s remarkable because it remains difficult to match Etruscan temples with their in-house gods or goddesses. Hailed as the best find in years, the 225-kilogram (500 lb) stele is expected to reveal new words as well as religious rituals and laws.

1 Rediscovery Of Senua

When a treasure cache arose in a Hertfordshire field, it soon became clear that it contained temple offerings to a highly regarded goddess. Plaques of precious metals were between the jewelry. Some plaques bore messages, thanking the goddess for her favors. Several also carried the symbols of the Roman goddess Minerva (owl, spear, and shield), but nowhere was the name written. To better read the faded writings, the plaques were X-rayed. A name emerged, but shockingly, it wasn’t Minerva. It was the name of an entirely unknown British goddess called Senua. Hoping to find out more, researchers returned to the same field. Incredibly, they found her—a dainty statuette made of silver. The 1,600-year-old female figure was named by its dislodged base, but Senua’s face remains unknown. It’s missing along with her arms. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages