10 Flores Giant Rat

Humans are easily frightened by the tiniest animals: Cockroaches, spiders, and mice seem specifically designed to scare the bejeezus out of us. Some grown men would even prefer to wrestle a bear or take on a pack of coyotes than let a mouse run up the leg of their pants. These men should probably avoid the island of Flores, Indonesia. It’s home to the Flores Giant Rat, which has the single virtue of being too large to fit up your pants leg. This isn’t the kind of rodent to be restrained by mouse traps: its body can reach 45 centimeters (18 in) in length, and that’s before you add its 75-centimeter (30 in) tail. Then the rat can exceed 1.2 meters (4 ft). This really is the stuff of nightmares, but at least most of us are physically big enough to fight off a giant rat. Unfortunately, the rats wouldn’t have been so easy to shrug off for our ancestors: Homo floresiensis, who shared Flores Island with them around 12,000 years ago. At around 1 meter (3 ft) tall, these early humans would have come face to face with rats frighteningly close to them in size. Luckily for the H. floresiensis community, Flores giant rats are believed to be vegetarians.

9 Nuralagus

The Nuralagus rex was a type of prehistoric rabbit, which developed into a giant due to its predator-free habitat on the Mediterranean island of Minorca. The largest specimens could have weighed around 22 kilograms (50 lbs), which is outrageous when you compare it to the 1.8 kilograms (4 lbs) of the largest modern rabbits. The tiny skull of the otherwise-giant rabbit suggests that its capacities for sight and hearing were significantly impaired compared to those of normal rabbits. This is most likely another result of the lack of predators on the island. With nothing around to kill it, there was no need to develop or maintain the traits necessary for competition and survival. As you can imagine, the extraordinary size of the nuralagus meant that it didn’t exactly hop around the island. It instead plodded quite slowly, more like a sloth than a rabbit.

8 Solomon Islands Skink

The Solomon Islands skink is unusual in many ways apart from the fact that it can reach nearly 75 centimeters (30 in) in length—three times larger than the average skink size. Unlike most reptiles, which usually produce offspring by laying eggs, the female Solomon Islands skink carries its young internally. When the baby skinks are born, they are sometimes already half the size of their mother. The giant skinks are sometimes referred to as “monkey-tailed skinks” because their tails have the unusual ability to grasp the branches of trees. But this ability comes at a price: The Solomon Islands skink is one of the few lizards unable to detach its tail at the approach of a predator. Lacking this advantage, it will often hiss and bite to defend itself.

7 Chappell Island Tiger Snake

At 2.4 meters (8 ft) in length, the Chappell Island tiger snake is the largest of all tiger snakes. For centuries, it has shared Mount Chappell Island, Australia, with a large number of local muttonbirds and absolutely no serious predators. Since it’s the only type of snake found on the island, it essentially has a monopoly over the muttonbird chicks, which it devours with relish every breeding season. The snake can eat so many hapless chicks in one six-week period that it often spends the rest of the year digesting its victims. Like many Australian snakes, the Chappell Island tiger snake is highly venomous, and its bite can be lethal to any human foolish enough to interfere in the muttonbird business.

6 Madagascar Giant Pill-Millipede

The giant pill-millipede of Madagascar is known by scientists as Sphaerotheriida, but locals have dubbed it more accurately as “star poo.” Though they look like normal millipedes in their relaxed state, they have the ability to roll themselves into an armored ball at the first sign of danger. Once they retreat into their armored plates, almost nothing can force them to unroll against their will. The largest pill-millipedes can reach the size of a baseball. Unlike centipedes but like other millipedes, the giant pill-millipedes are non-venomous, and they live on a diet of decaying plant matter.

5 Saint Helena Giant Earwig

“Absolutely horrifying” is probably a reasonable description of the Saint Helena earwig, which can reach nearly 10 centimeters (4 in) in length. First discovered in 1798, the giant earwig has been inhabiting nightmares ever since. The folk belief that earwigs are capable of crawling into human ears and eating brains is now well-known as a myth, but if you still harbor any fears, then rest assured: The Saint Helena earwig is actually too enormous to even fit in your ear. Believe it or not, the hideous exterior of the Saint Helena earwig actually conceals a warm, loving, and tender interior. The giant species is renowned among earwig researchers for its unusually advanced levels of maternal care. After the eggs have been laid, the mother frequently cleans them to protect them from fungi and is known to defend them from predators. The giant earwigs, like Napoleon in his later years, are endemic to the tiny Atlantic island of Saint Helena. There have been no sightings since about 1967, leading many to believe that extinction may have occurred as a result of predation from the introduced centipede.

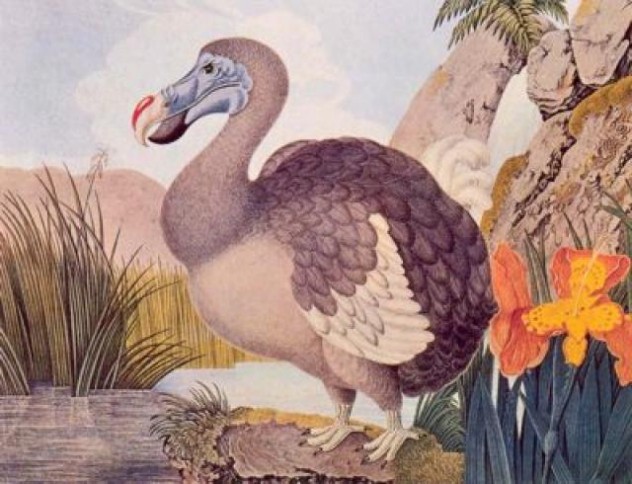

4 The Dodo

The dodo—a kind of gigantic, flightless pigeon—is not quite so terrifying as other entries in this list. But dodos are a still a very good example of island gigantism at work. Isolated for thousands of years on the small Indian Ocean island of Mauritius and completely lacking any major predators, dodos were completely fearless of humans. The story of human contact with dodos is a famous one. When Dutch sailors arrived in the 16th century, they found the large, plump, overfed birds rather laughable. Despite the meek, trusting nature of the dodos, they were routinely butchered for food by humans, and their flightlessness made them easy prey for even the laziest of introduced predators. This slaughter, coupled with the fact that the dodos couldn’t reverse the evolutionary trend of thousands of years in a matter of decades, led to the species being exterminated by the end of the 17th century.

3 Galapagos Islands Giant Tortoise

The giant tortoises of the Galapagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador have the potential to outlive any other vertebrate. They can routinely live for over 100 years, and one of them held on until the ripe age of 152. They’re also true giants of the tortoise world: Some subspecies can reach 250 kilograms (550 lbs) and over 1.5 meters (5 ft) in length. At the time of Charles Darwin’s famous visit, there were 14 different subspecies of giant tortoise in the Galapagos Islands. Each kind of tortoise originated from a single ancestor, but their evolution began to diverge after they found themselves on different islands with different challenges and began to evolve accordingly. Giant tortoises display a fascinating form of symbiotic behavior when it comes to ridding themselves of parasites such as ticks. Whenever they’re in need of pest removal, they stretch up on their hind legs, allowing passing birds to peck away all the ticks. The number of subspecies has now dwindled to 10 after centuries of hunting, poaching, and the introduction of domestic animals. Taken together, these things probably killed more than 100,000 giant tortoises. But thanks to the increased efforts of conservationists, only 120 of the 15,000-strong population have been killed by poachers since 1990.

2 Giant Fijian Long-Horned Beetle

The giant Fijian long-horned beetle is the second-largest beetle in the world, reaching an extraordinary body length (by beetle standards) of 15 centimeters (7 in). The beetle lives a simple life in the trees of Fiji on a diet of plant matter, but anyone who is generally creeped out by insects will still find cause to be uneasy: The horns which give the beetle its name can also reach lengths of more than 12 centimeters (6 in), meaning that its horns are often nearly as long as its gigantic body. The larvae take 12 years to reach their full adult size. Many of them don’t survive that vulnerable period, since the larvae are sought out as a rare delicacy by Fijian villagers. Several tribes consider them to be sacred, and only the village high chief is permitted to eat them. But the few long-horned beetles which make it into adulthood become truly fearsome: “Powerful jaws” and “very loud whirring noise when flying” are just some of the phrases insectophobes don’t like to hear. Upon being disturbed, the beetles will also respond with an alarming hissing noise.

1 Elephant Bird

The aptly named elephant birds of Madagascar were around 3 meters (10 ft) tall and could weigh 400 kilograms (900 lbs). If you have ever seen an emu or ostrich and been amazed by its size, then you’ll understand how early visitors to Madagascar must have felt when they caught sight of these creatures before the species died off in the late 17th century. Elephant birds were probably the largest birds ever to have lived. Even their eggs were a full meter (3 ft) in circumference, and their fearsome appearance gave rise to the legendary “Roc” of Arabian folk tales. This fabled creature was thought to consume elephants, but such a rumor says more about the effect of the elephant birds on travelers’ imaginations than their actual feeding habits. The real elephant bird was more heavily built than the more familiar moa of New Zealand, and its eggs were even larger.