10Grandison Harris

Grandison Harris was a slave who belonged to the Medical College of Georgia. Bought in 1852, he was officially the school’s porter and janitor. Unofficially, he was their body snatcher. Like others who shared his grisly profession, he was also known as a “resurrection man,” and his slave status afforded him something of an odd benefit when it came to this second job. As a slave, he couldn’t be prosecuted by the law. Harris spent more than 50 years unearthing freshly buried bodies and supplying the students of the medical college with corpses to dissect and learn from. His forward-thinking employers gave him all the tools that he needed to be a successful body snatcher—they even taught him how to read and write, so he could keep an eye on newspaper obituaries himself. Harris had uncanny flower arrangement skills, which came in handy when he needed to reassemble funeral flowers after removing a body. But many times, that wasn’t even an issue. One of his favorite stomping grounds was Cedar Grove Cemetery, where the most impoverished people were buried in coffins that were easily shattered by an axe. After the Civil War, Harris found himself a free—and learned—man. He took a position as a judge in a small Georgia town, but the students he had formerly supplied with dead bodies weren’t about to let him forget where he came from, no matter how powerful he was by day. Harris continued his grave-robbing activities and brokered deals to supply the college with slightly more legitimate bodies, purchased from prisons and hospitals. He also spent his later years teaching the finer points of grave robbing to his son, who ultimately replaced him at the college. In 1908, Harris gave a lecture at the college, teaching others just how he managed to be such a successful resurrection man. He died in 1911 and was buried in the same Cedar Grove Cemetery where he’d spent so many lamplit nights. Perhaps as a precautionary measure, there’s no grave marker, only a monument. No one knows exactly where his body was actually buried.

9The Plot To Steal Abraham Lincoln’s Body

Not all body snatchers were working in the medical field; some were simply out for themselves. In the 1870s, Chicago was home to a gang of counterfeiters run by “Big Jim” Kennally. All was well, until he lost one of his top engravers to a 10-year stint in Joliet. But Kennally wasn’t about to let his man sit in prison if he could help it. Somehow, Kennally and his gang hit upon the idea of stealing Abraham Lincoln’s body and holding it for ransom: $200,000 and the release of their colleague. For some bizarre reason, the two men Kennally hired to do the body snatching part of the plan had absolutely no experience in the field. The men, a nickel-maker and a saloon owner, decided they were going to need a little help and hired a third man to help them. Unfortunately for them, the man they hired was on the payroll of the then-infant Secret Service. Their Secret Service assistant went through with the plan, all the while telling the government exactly what was going on. When the time came, they headed to the cemetery, cut the padlock off the crypt (as no one knew how to pick the lock), and were temporarily halted when they realized they had no way of moving the concrete slab that sealed the tomb. The Secret Service was about to arrest the men, but then someone’s gun went off, alerting the ill-fated criminals to their presence. Fortunately—as we’ve already established—the body snatchers weren’t that bright. They were apprehended when they retreated back to the saloon owner’s bar.

8Body Snatching In The Wrong Place

London Hospital was just one of the many places in Britain that used real corpses as teaching tools for their students. A recent archaeological dig at the school found countless piles of bones buried behind the college in unmarked graves and containing the remains of an estimated 500 people. Many of them had died in the hospital and then were disposed of after being used for medical research. In fact, the sheer number of people who went through the London Hospital—and died there—meant that the place was in a rather unusual position. It had more bodies than it could use, so the hospital started selling the bodies to other institutions. It might seem like a reasonable way to make some extra cash, but it wasn’t entirely legal. Because of this, most of the body removals were done at night, and one William Millard might have been an unfortunate casualty of the practice. In 1832, he was arrested in the hospital’s burial grounds and charged with being a body snatcher. There wasn’t actually any evidence implicating him, but it didn’t really matter. He eventually died in prison, but his wife protested his innocence long after his death. According to her, he was there to pick up some of the hospital’s extra bodies to take them to a buyer. She claimed that his only crime was being in the wrong place at the wrong time, doing something that the hospital might have sanctioned but didn’t quite want to become common knowledge.

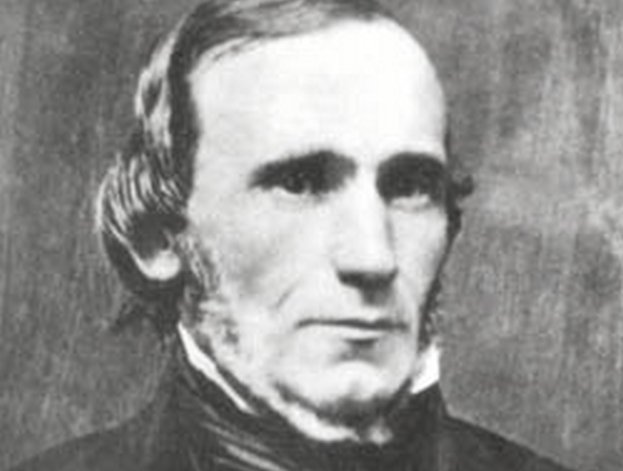

7John Scott Harrison

John Scott Harrison was the son of US President William Henry Harrison and the father of another president, Benjamin Harrison. He was also at the center of one of the most horrific cases of body snatching in US history. A beloved congressman and father, he died at the age of 73 and was buried in the Congress Green Cemetery, near the Medical College of Ohio. While the family was burying their beloved patriarch, they noticed that the grave of John Scott’s recently deceased nephew, Augustus Devin, had been disturbed and the body taken. After the funeral, John Harrison, son of the recently buried John Scott, took a local constable and a search warrant to the Medical College of Ohio to look for the body of the young man. There were only a few bodies there, and nothing looked outright amiss, but the janitor who was showing them around was noticeably squirrely. John might have turned and left, if he hadn’t seen something suspicious: a rope and a series of pulleys, leading down to a lower level of the school. When they winched the heavy rope up, they found a body . . . but not the body they were looking for. It was John Scott, recently buried, more recently disinterred, and horribly disfigured and damaged. The younger John, faced with the body of his dead father, started a campaign against the college that soon threatened to escalate to mob violence. The college defended their right to use bodies for dissection—saying that they hadn’t known where any of said bodies were coming from—but it wasn’t over yet. The investigation also uncovered the body of Augustus Devin, rotting in a vat with about 40 other bodies. Both John Scott and Augustus were reinterred, and two local body snatchers were arrested. However, lawsuits filed against the college had less-than-stellar results.

6Bishop, May, And Williams

Sometimes, graveyards didn’t have enough fresh bodies for the resurrection men to keep up with demand. John Bishop had been operating as a body snatcher for about 12 years when he and his partners decided to go from stealing dead bodies to making some of their own. Some targets were easier than others. In November 1831, Bishop and his cohorts presented their latest acquisition to anatomy instructors at King’s College in London. While the instructors presumably had no qualms about repurposed bodies, they did grow suspicious when presented with the body of a young boy who had rather telling wounds on his head. Keeping Bishop there with the story of needing to get change for a £50 note, the instructors summoned the police. Eventually, it was found that the group had been preying on street urchins and beggar boys. Even though the body snatchers started pointing fingers at each other while denying knowledge of the crimes, John Bishop, John May, and Thomas Williams were eventually tried and convicted for the murders of 14-year-old Carlo Ferrari, 10-year-old Cunningham, and a 35-year-old woman. In addition to selling their bodies, the trio also made some side money by knocking out their teeth and selling them to dentists. Before Bishop was hanged, he proudly declared that he was responsible for brokering deals with anywhere from 500 to 1,000 bodies. The story would go on to inspire a young writer named Charles Dickens, who would use the plight of the orphaned beggar boys in several of his novels—most notably, The Pickwick Papers. The body snatchers were hanged and then handed over to medical students to dissect.

5University Of Maryland And ‘Frank’

According to an 1828 recruitment advertisement from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, the school was “the Paris of America, where the subjects are in great abundance.” Those subjects were, of course, corpses, and the abundance of dead bodies was said to be the work of “Frank.” His last name isn’t known, but Frank’s prowess in uncovering and returning with dead bodies was well documented in a series of letters between college staff and professors. One of his favorite haunts was said to be the Westminster Burying Ground, where he supposedly made off with so many bodies that the school had an excess of them. According to letters from Dr. Nathan Ryno Smith, bodies would be sold to other schools and, in order for them to make the journey without decomposing (or smelling), they were packed in whiskey barrels. Rumor had it that when the bodies made it to their final destination, students that were unable to see why they should waste perfectly good whiskey would drink it. Other versions of the rumor had Frank himself bottling the used whiskey and selling it to area bars. Not everyone was a fan of using human bodies to teach medical students, however, and by 1831 Frank was fearing for his life. The school’s practices had long been protested by the locals, and one of the medical school’s original buildings had been attacked by an angry mob and torched. The new building—Davidge Hall—was built in 1812 and included secret passages and trap doors for escape . . . just in case. One of the cadavers is still there, and his name is Hermie.

4Elizabeth Ross

While body snatching is mostly a man’s world, there was one woman who met the same grisly end as notable names like Burke and Hare. Elizabeth Ross was convicted, executed, and handed over to the same medical students that she’d supposedly supplied, all for the murder of her family’s lodger. According to records from the trial, Ross was well known not just for her love of gin but also for being a thief. She was painted as a big, burly, almost manly Irish woman, who had the strength to easily commit such a heinous murder and then carry the body away to sell it to the London Hospital. However, Ross claimed she’d last seen their lodger alive and in the company of Ross’s 12-year-old son and his father, Edward Cook. The evidence against Ross was pretty nonexistent, and it appeared that her son, who had testified against her, was more interested in saving his father than his mother. Also, a sketch of Ross made before her corpse went under the doctor’s knife showed a rather slight woman. Nevertheless, she was found guilty by a city that was all too familiar with nighttime grave robberies and murders. It was said that neighborhood cats often disappeared around Ross’s home and that she was exactly the kind of person who would do such a horrible thing to cash in on the money. Regardless of whether or not she was guilty, Ross was executed for the crime and found herself on the dissecting table.

3Snatching Bodies Before Burials

While our traditional image of body snatching is of dark, moonlit cemeteries and questionable figures digging through the freshly turned soil of a new grave, not all body snatchers waited until a corpse was buried to grab it. In 1830, London police testified to recovering nearly 100 bodies that had been stolen from homes while their wakes were still being held. One incident, attributed to a well-known body snatcher, Clarke, was the theft of the body of a four-year-old girl who had been laid out in the home of a nurse. Clarke scouted the house and the location of the body. He then shared a drink with the nurse in memory of the dead girl. He left but then returned when he knew the nurse would be deep in alcohol-induced sleep and stole the body of the little girl. The body was recovered by a police officer who recognized Clarke when he was about to sell it. Clarke was arrested and given a jail sentence of six months. In some cases, these bodies weren’t destined to be sold for medical research. Some were ransomed back to the families, while others were used in even more bizarre schemes. Bodies of suicide victims would be stolen while waiting for examination and ultimate ruling by a coroner. Body snatchers would sell the corpse to a teacher or surgeon, then report their sale to the police. Police would seize the body and return it to the relatives. The “relatives” waiting to claim the body would be the body snatchers themselves, who would then turn around and do the whole thing all over again.

2Saved By The Body Snatchers

As if the idea that your body was at risk of being stolen after your death wasn’t bad enough, the same time period also saw the fear of being buried alive. According to one broadsheet newspaper story, that’s exactly what happened to John Macintire on April 15, 1824. According to the terrifying account, Macintire was alive through his family gathering around what they thought was his deathbed and through the mourning that happened over his coffin at his wake. Macintire wrote that he remembered being sealed in the coffin and carried to the graveyard and that he could do nothing as he listened to the dirt being thrown on top of his coffin. And then . . . silence. He described the horror of nothingness, of darkness around him, of being unable to move as he thought of the worms and the bugs that would soon work their way in. Then, he described the digging. Macintire was stripped of his shroud and rather unceremoniously conveyed from the grave to a dissection table. He heard the voices of the students and the doctors that were filing into the room for the lecture that he was to be an integral part of. It was the feel of the knife slicing through the flesh of his chest that finally woke Macintire from his paralyzed state. The doctors, realizing that their “corpse” wasn’t quite fully dead, successfully revived him.

1So How Much Did They Make?

Body snatching wasn’t just against the law, it was ethically, morally, and religiously questionable, too. Body snatchers were at the bottom of society, and most of those who turned to body snatching didn’t have far to fall. So how much did they make, and was it really worth their while? According to records from the early 1800s, a typical adult corpse in London was worth about four pounds and four shillings. That’s about $447 in today’s money. The body that got the abovementioned body snatchers Bishop and May in trouble had an agreed-upon price of nine guineas, or about $1,469 today. According to the lamentations of those running the Blenheim Street School, demand for bodies had driven up the prices considerably; students whose teacher had paid two guineas (around $319) could end up purchasing bodies at a ridiculous 16 guineas ($2,235) by the time they became teachers themselves. More and more universities were using corpses to teach. Schools were forced to either pay what body snatchers were demanding or see them go elsewhere and sell the bodies to other schools. In addition to selling the bodies, many would also remove the teeth to sell separately to dentists. Some records show dentists offering five pounds (around $560) for a set of teeth. Not a bad living for someone scraping by in the early 1800s . . . if you could stomach it. Read More: Twitter