10The Peltasts

Peltasts were Greek light infantrymen and skirmishers of the late fifth century. Usually recruited from the ranks of Thracian mercenaries and citizenry, they were the original peasant army. They were most often armed with spears, javelins, or slings, and they used light shields called pelts, from which they get their name. The peltast forces would open a battle, launching their javelin or sling attacks, and then retreat to let the better-protected phalanx move in. As the phalanx cleared the way, the peltasts would advance again, and the process would repeat itself until both armies were engaged in close quarters. Peltasts generally wore no armor and fared poorly if forced into hand-to-hand combat. However, these brave skirmishers fought alongside their much better-protected phalanxes, sowing panic and confusion among the enemy hoplite phalanxes and maintaining the ability to avoid attack. Peltasts even went at it with Spartans, playing an important role in the Peloponnesian Wars in 425 B.C. at the island of Sphakteria, where the Spartans faced a nearly unprecedented defeat at the hands of the Athenians.

9The Cataphraoti

The cataphraoti were a class of heavy cavalry created to counter the infantry of the Iranian Parthian Empire in the third century. The first reference to them comes from Livy, who notes their presence in Antiochus III’s Seleucid army of horsemen. Both horse and rider wore knee-length full-scale armor made of steel or bronze, and the rider also wore a steel helmet. They were armed with kontos, a type of spear up to 4.5 meters (15 ft) long, as well as a variety of daggers. They also carried a compound bow, which they often shot backward as they retreated in the famous “Parthian shot.” Sometimes, cataphracts were supported by camel riders or riderless camels that bore arrows and made up a mobile ammo depot. These elements made the cataphracts a greatly feared enemy. The Romans were so impressed with the cataphracts that they incorporated a similar form of cavalry into their own armies, who became the early prototypes for the medieval knight.

8The Genitors

The genitors (or jinetes, which means “horseman” or “rider”) were a class of warriors common in 14th-century Spain that wielded swords as well as lances or javelins. They were also known to sometimes use darts called assegais. While they were considered light cavalry, they often wore heavy armor consisting of mail hauberks with bascinets and cuirasses. They also had shoulder, elbow, and knee guards made of plate. They employed heart-shaped shields, like most medieval knights, while their horses were either armored lightly or not at all. The genitors were formed as a response to devastating attacks by Moorish cavalry during the Reconquista. As such, they were developed to be as close a match as possible to their Moorish enemy. They were highly skilled horsemen who could only be effectively countered by missile fire or the use of similar cavalries. As skirmishers, genitors could dance circles around most infantry, famous for the way they dashed in and out of reach.

7The Conquistadors

When Columbus arrived in the New World, Spain wasted little time expanding its empire into the region. Their main agents were the Conquistadors, a fearsome infantry that also consisted of explorers, governors, and exploiters who acted as missionaries, converting the native populations of conquered regions to Christianity. Conquistadors usually wore armor made in Toledo, Spain, as “Toledo armor” was some of the strongest known at the time. Cavalry used 3.5-meter (12 ft) lances and one- or two-handed broadswords, while foot soldiers used bows and short swords for close combat. While early firearms like the arquebus were available and may have sometimes been used, they weren’t fit for the tropics and would have been rare. While the term conquistador can be applied to any member of the Spanish army in the New World, it is popularly associated with its leaders. Because these men operated so far from home, they often acted with a great deal of autonomy. Legendary Conquistador Hernan Cortes actually had his appointment to the Americas withdrawn, but he set sail before the orders could go through. By the time Spain could send agents to arrest him, he was well established, and he often turned those agents to his cause. He left with only 10 vessels, 600–700 Spaniards, 18 horsemen, and a few cannons, but he still managed to conquer what is now Mexico. He even destroyed his ships behind him to let his men know that retreat was not an option. While many people believe he burned his ships, he actually sunk them. The plunder of the New World continued with Conquistadors like Juan Ponce de Leon, Francisco Pizarro, Panfilo de Narvaez, and Hernando de Soto. By the time the Spanish Orders for New Discoveries in 1573 curbed the excesses of the Conquistadors, they had left another lasting legacy—smallpox, malaria, measles, and sexually transmitted diseases. These diseases had never been seen in the New World, and the natives had no resistance to them.

6The Musketeers

Once guns came into play in the 14th century, warfare was changed forever. By the 15th century, the first musketeers sprung up in China, the Ottoman Empire, India, Russia, and throughout Europe. The first special guard of French musketeers was formed in 1600 by King Henry IV. They were armed with carbine-style firearms and called the King’s Carabineers. With the introduction of muskets, they became the romantic musketeer of mythic proportions known as the French Musketeers of the Guard, an elite unit consisting of nobles and the very best soldiers culled from the infantry. In battle, they were proficient in pistols, earning a reputation as lauded duelists, as well as their famous rapiers and a type of dagger called the main gauche. They were equally deadly on foot and on horseback. In addition to participating in campaigns, it was their personal duty to defend the king and his household, compelling other powerful men to organize their own musketeer guards. The antagonist of Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers, Cardinal Richelieu, introduced the blood red tabard, but blue and black were also used. Whatever the color, the tabard of the musketeer also displayed a cross and the fleur de lis crest. They also wore leather gauntlets, dueling pants, black suede boots, and the jaunty leather cavalier hat. The royal Musketeers of the Guards were disbanded for good in 1816.

5The Mamluks

The Mamluks (meaning “possessed” or “owned,” generally referring to military slavery) began their history as a slave warrior caste under Islamic sultans. They were drawn mainly from the Qipchak Turks in Central Asia, while the Bahri Mamluks were drawn from southern Russia and the later Burgi from the Circassians of the Caucasus. The Mamluks were cavalry units who were also trained in fencing and the use of the lance, mace, and battle axe. They followed their own strict code closely based on the principle of furusiyya, representing ulum (“science”), funun (“arts”), and adab (“literature”). Furusiyya was a moral code but also an art and a teaching guide in tactics, horse care, mounted archery, and warfare in general. Despite their adherence to furusiyya, the Mamluks were mostly illiterate. Usually captured around the age of 13, they were converted to Islam and given elite training for personal use by sultans or higher lords. They went on to become a ruling class after the conquer of Egypt and Syria, when the Mamluks forced a marriage between their commander Aybeg and the widow of the last sultan in 1250. In the midst of intense and brutal political infighting, the Mongols arrived. They had taken almost all of Islam’s heartland when the Mamluks, in power for less than a decade and bitterly divided, defeated them and saved all of Syria and Egypt from the horde. The Mamluk dynasty ruled Egypt and Syria until 1517, when they were overthrown by the Ottoman Empire. While they ruled, the Islamic kingdom became a hub for the arts, scholarship, and craftsmanship. Not bad for former slaves.

4The Landsknechts

In the late 15th century, Germany developed the Landsknechts (meaning “servant of the country”) to counter the extremely effective Swiss infantry. Early forms of the Landsknechts were so thoroughly modeled after Switzerland’s excellent halbadier and pikeman soldiers that they were sometimes referred to as “counterfeit Swiss.” They were first formed under Maximilian I with the assistance of Georg von Frundsberg (the “father of the Landsknechts”) and went on to fight in many of the major engagements of the 16th century, sometimes on both sides. Many Landsknechts were arquebusiers, marksmen armed with an arquebus and bandoliers of power tubes, an early type of bullet. They also also used a polearm and a short sword called a Katzbalger, which became a symbol for them. They often wielded two-handed or hand-and-a-half swords, which could be used to sweep aside pike walls. Cavalry forces were nearly useless against the combination of firearms and polearms, leading to their adoption all over Europe. The most distinctive characteristic of the Landsknechts were their costumes. They wore headgear with large feathered hats and flamboyant garments of puffed and slashed construction that revealed inner costumes of contrasting colors, with layers of mail or other protective clothing both on top of and underneath their costumes. In the end, their mercenary nature proved to be their undoing. Despite swearing oaths to never fight with “enemies of the empire,” their international involvement in conflicts led to their decline around the middle of the 16th century. Their characteristic colorful costumes faded away until they were replaced by imperial foot soldiers called the Kaiserliche Fussknecht, who would become the forerunners of modern soldiers.

3Maori Warriors

For centuries, New Zealand was locked in a seemingly endless cycle of warfare. These conflicts ushered in the elite Maori warrior class, tattooed fighters armed with several unique weapons who fought in bands of a few hundred men. Their principle weapons included the patu (a short club made from wood, bone, or greenstone), the waihaka (a polished wooden club with a notch for disarming an opponent), the kotiate (a double-notched flat club that chiefs also used in speech-making), the taiaha (a 1.5-meter [5 ft] club), and the toki pou tangata (a large, tomahawk-like weapon made of wood with a greenstone blade). The Maori were highly skilled warriors who counted both men and women in their ranks. They excelled in stealth and guerrilla tactics, and they trained using martial arts and several forms of dancing, the most well-known of which is called haka. The haka also induced psychological effects, designed to make the warrior intimidating and fearful of aspect. The time before a battle was highly ritualized, featuring fasting and dancing. Maori warriors fought to the death to ensure that there was no one left to seek revenge, or utu. When fighting, they often stuck their tongues out at the enemy. This was an insult of the highest order, meaning “I will kill you and eat you.” It wasn’t an idle threat—captured enemies were often eaten, after which their heads were preserved with head-shrinking, their bones were made into fish hooks, and their blood was drunk.

2The Janissaries

The first Janissary Corps were formed in 1380 by Sultan Murad I Bey. Their name was taken from the Turkish yeni cheri or yani cheri, meaning “new soldiers.” Their numbers quickly grew until they became some of the most feared warriors of the Crusades. The infamous whirling dervishes that frightened Europe were drawn from their ranks. Janissaries were originally archers, but by the 15th century, they had adopted muskets. The Janissaries were recruited solely from the ranks of Christian slaves. They evolved from the practice of using captured slaves as mercenary units during the Ottoman Empire, but by the time of the capture of the Balkans, the Turks began taking tribute in the form of male children as slaves. Some of these children were chosen to be trained over a period as long as 10 years to become Janissaries. They were virtual killing machines, generally recognized as some of the best-trained and most effective soldiers of the 16th and 17th centuries. They were also sworn to Islam and freed of any local political connections that could be a danger to their leaders. Janissaries were also some of the best-paid soldiers of the period. They drew a cash salary in times of both war and peace in addition to a hefty share of any spoils. For centuries, their loyalty was beyond reproach, but around 1826, they were replaced with a modernized army after many revolts. Subsequently, their effectiveness declined. They were steadily granted more rights that undermined their loyalty until their autonomy eventually led them to lose their political neutrality, and they became a threat to the state.

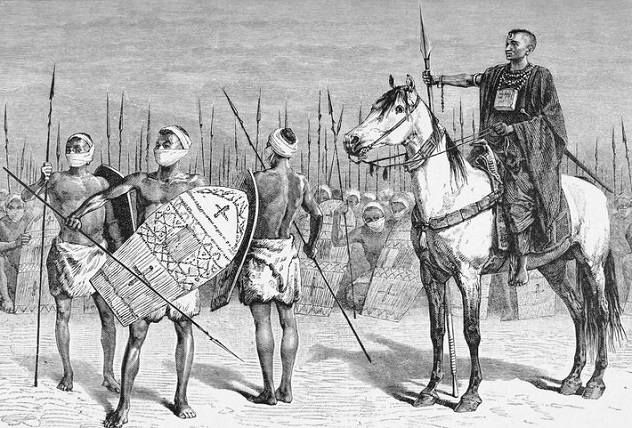

1The Kanuri Cavalry

The European colonialists who went to battle in North Africa in the mid-19th century must have thought they had traveled back in time when they were confronted by the elite cavalry of the Kanuri people. They soon learned not to laugh. The Kanuri people lived northeast of Lake Chad in Kanem-Bornu, a kingdom that existed from the ninth to the 19th century. While the court was officially Islamic, the mai (king) also recognized and permitted traditional beliefs. The kingdom was dissolved by French colonialists in 1900. At its height, it had expanded as far as the Niger River to the west, Wadiai to the east, and the Fezzan to the north. They did all this with the help of the Kanuri cavalrymen. The soldiers and their horses were both clad head to toe in an astonishingly strong quilted cotton or padded armor, wielding swords and lances. The cavalrymen in many regions had helms made with brass and ostrich feathers but generally did not carry shields. Some places, particularly Cameroon, had access to mail armor as well, and all were elaborately decorated with a rich variety of symbols and patterns based primarily on clan membership. The Bornu horsemen also boasted trumpeters, who led the troops into battle. Lance LeClaire is a freelance artist and writer. He writes on subjects ranging from science and skepticism to religious history and issues to unexplained mysteries and historical oddities, among other subjects. You can look him up on Facebook or keep an eye out for his articles on Listverse.