Despite many Mamluks being the captured sons of Christians, Jews, pagans, and other non-Muslim religions, the Mamluks quickly gained a reputation for being zealous jihadists. Indeed, their gory conquests outdid those of the famous Muslim warrior Saladin and his Ayyubid Empire, which the Mamluks overthrew in 1250. At their height, the Mamluks controlled Egypt, northern India (including the major city of Delhi), the cities of Aleppo, Damascus, and Jerusalem, and the nation which would become known in the 20th century as Iraq. It was the Mamluks who finally defeated and destroyed the last remnants of the Crusader states in the Middle East, and Mamluk forces held their own against the Ottoman Empire and the French Army of Napoleon. These fascinating soldiers deserve to be studied more, and we hope that this list is part of that correction.

10 Slave Origins

The Arabic term mamluk simply means “property.” The first Muslim power to use such slave soldiers was the Abbasid Caliphate based in Baghdad. Under Abbasid rule, the Islamic Empire enjoyed what is commonly called its “Golden Age.” The Abbasid court oversaw the “Persianization” of the Islamic world, with Arab scribes and scholars translating Zoroastrian texts on medicine, philosophy, art, and poetry. Similarly, Abbasid scholars developed their own interpretations of the Greco-Roman texts that they found after Muslim armies seized Egypt.[1] Despite this flowering of culture, several of the Arab and Berber rulers of North Africa and Spain felt that the Abbasids had given up on the holy cause of converting the whole world to Islam. In the autonomous states of the Cordoba Caliphate of Spain, the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt, and Ghaznavid Empire of Central Asia, more stringent brands of Islam prevailed, which resulted in increased persecution of Christians and Jews in those areas. To retain their control over North Africa and Central Asia, the Abbasids began converting the nomadic Turkic people of the Pontic and Caspian steppes. Christians from the Mediterranean and Caucasus Mountains were also converted or captured by the Abbasids. Many of these converts had been sold into slavery by their impoverished families. Once Muslim, these slaves were trained to be excellent cavalry soldiers. The Mamluks pledged their loyalty to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. Such a system would later be adopted by the Turkic Ottoman Empire, which used its slave Janissary soldiers to conquer large parts of southeastern Europe.

9 Takeover Of Jerusalem

Unfortunately for the Abbasids, Turkic Muslims proved to be independent-minded. In fact, the marauding Turks earned a much more fearsome reputation among Christian powers than their Arab predecessors. In August 1071, the mighty Byzantine Empire was decisively defeated by the Seljuks, a Turkic confederation that included Mamluk veterans, at the Battle of Manzikert. Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes was captured during the battle, and from that point on, the Byzantine Empire would never be able to reclaim its control over most of Anatolia.[2] Two years later, Seljuk Sultan Malik-Shah I captured the holy city of Jerusalem. Under Malik-Shah’s reign, Seljuk Turks, with the blessing of the Abbasid caliph, conquered the breakaway territories of Mesopotamia, Azerbaijan, Syria, and Khorasan. While Malik-Shah’s sultanate did earn a reputation for learning (including supporting the poet-intellectual Omar Khayyam), his conquest of the Holy Land saw horrific massacres that turned Christendom against his rule. This set the stage for the First Crusade, which was preached by Pope Urban II as a specifically anti-Turk war.

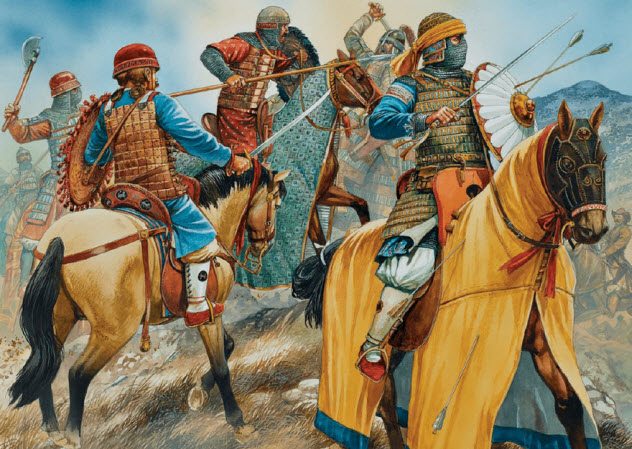

8 Ayyubid Soldiers

Arguably the greatest military general in Islamic history is the Kurdish warlord Saladin. Salah al-Din Yusuf Ibn Ayyub, or Saladin, was the nephew of Shirkuh, an earlier Kurdish general who was employed by the feared Turkic ruler of Aleppo and Damascus, Nur ad-Din. Under orders from Nur ad-Din, Shirkuh invaded Egypt to stop the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem from conquering the main grain-producing parts of that country. When Saladin came of age, he took control of Egypt and purged it of the Shia Fatimid Caliphate. Prior to his famous exploits against the Crusader army under the command of English King Richard I (“The Lionheart”), Saladin carried out a murderous military campaign against the Shia in Egypt and established Sunni Islam as the official religion of the new Ayyubid Sultanate. The Ayyubid army, which earned battlefield distinction and captured the city of Jerusalem after 88 years of Christian rule, was primarily composed of Mamluk horsemen and foot soldiers. Until its collapse in 1250, the Ayyubid Sultanate relied overwhelmingly on the strength and skill of its Mamluk soldiers.[3]

7 Fighting The Fifth And Seventh Crusades

Even though Saladin thwarted the Crusaders’ desire to seize Egypt, this does not mean that the remaining Christian forces in the Middle East or the various kingdoms of Europe had given up on the idea of seizing Cairo, Alexandria, or Damietta. Beginning in 1219, Christian armies began invading the northern reaches of Egypt. One army, led by Spanish Catholic Cardinal Pelagius, captured the port city of Damietta. This army, which included the Knights Templar, tried to take the Ayyubid capital of Cairo. But their plan failed. Before long, the Crusaders were low on supplies and men, which forced them to abandon Egypt. In December 1244, King Louis IX of France launched the Seventh Crusade with 100 ships and approximately 35,000 men to capture the major cities of Egypt. The idea was to capture Damietta, Alexandria, and Cairo to exchange these cities for Syrian municipalities like Aleppo and Damascus.[4] On June 6, 1249, King Louis’s mainly French army seized Damietta. However, this victory proved short-lived when the Crusaders failed to capture the important fort of al-Mansurah. This stopped the Seventh Crusade from gaining Cairo. In almost every battle of both these crusades, the Mamluk soldiers squared off against the Christian knights and peasant soldiers of Western Europe. Indeed, following the capture of Damietta, Shajar Al-Durr, the Ayyubid queen, won control of political power in Cairo thanks to support from the Mamluks. In March 1250, King Louis IX, later to become Saint Louis in the Catholic Church because of his famous piety, was captured by Mamluk soldiers and ransomed for 400,000 livres.

6 The Seizure Of Egypt

The initial success of the Seventh Crusade helped to further fracture the political situation in Ayyubid Egypt. Ever since the death of Saladin, the Mamluk soldiers had had a significant say in political matters. After all, the Ayyubid army was dominated by Mamluk captains and generals and these men were not shy about using the threat of violence to keep the Ayyubid sultans in line.[5] When Shajar Al-Durr became the undisputed leader in Cairo, the Mamluks exerted pressure on her to get married. The man she ultimately married was a Mamluk general named Aybak. With this marriage, Aybak became the first Mamluk sultan of Egypt. Although Aybak died ignobly after being assassinated while taking a bath, he did found the Bahri dynasty, a Muslim ruling family of Cuman-Kipchak Turk origin. From then until the 16th century, Egypt would be in the hands of Mamluk sultans. Most of them were also of Turkic origin.

5 The Most Terrifying Warlord

Baibars (aka Baybars) is the most famous (or rather infamous) of the Mamluk sultans of Egypt. Baibars’s rise to power is one of the most unlikely stories in history. Before becoming the fourth sultan of Egypt and Syria, he was an impoverished Kipchak Turk born near the Black Sea. In 1242, the Kipchak state was conquered by the Mongols. As a result, Baibars was sold into slavery and purchased by Ayyubid Sultan as-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub. Due to his outstanding military skills, Baibars was named the chief of the sultan’s bodyguards. Baibars’s first victory as a military commander came during the Seventh Crusade when his army turned back King Louis IX from al-Mansurah. When Aybak seized the Ayyubid throne, Baibars was forced to escape to Syria because of personal animosity between himself and Aybak. Baibars remained in Syria for a number of years. In 1260, Baibars returned to Egypt at the invitation of Mamluk Sultan Qutuz. He wanted Baibars to lead an army against the invading Mongols, the most feared military in the world during the 13th century. Sultan Qutuz hoped that Baibars would be able to defeat the Mongols, something that almost every commander in the world had failed to do at that point in time.[6]

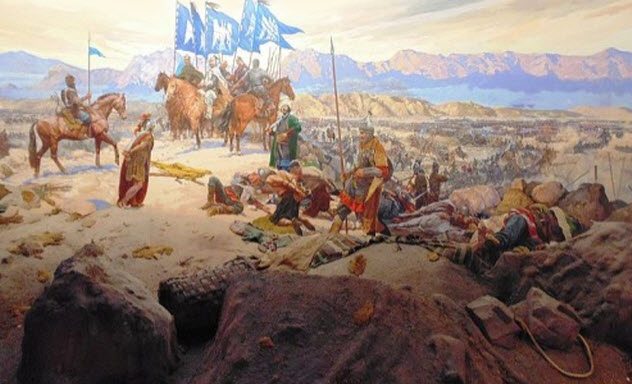

4 The Battle Of Ain Jalut

Beginning in 1260, the Mongol leader Hulagu sent emissaries to the court in Cairo to negotiate the surrender of the Mamluk sultan. Hulagu’s letter warned Sultan Qutuz to “think of what happened to other countries and submit to us.” Sultan Qutuz responded to this threat by killing the two Mongol emissaries and placing their severed heads on the gates outside Cairo. A massive Mongol army gathered in Syria and Palestine to take on the stubborn Mamluks. Unknown to the Mamluks, a civil war was brewing over the naming of the next Great Khan in Mongolia. Hulagu raced back to Mongolia to get his brother Kublai named as the Great Khan instead of Arik-Boke. Ultimately, Kublai would become khan, the creator of China’s Yuan dynasty, and the greatest Mongol conqueror besides Genghis. On September 3, 1260, the 20,000-man Mongol army, which Hulagu had left behind in the Levant, faced off against a similarly sized Mamluk force. At the Ain Jalut oasis near the Jezreel Valley in Palestine, the Mamluks used a feigned retreat to lead the Mongols into a trap.[7] This is precisely what happened, and the faster horses used by the Mamluk cavalry overwhelmed and decimated the Mongols. The Mongol commander, Ketbuqa, was decapitated. This victory marked the beginning of the end for Mongol expansion into the Mediterranean world.

3 The Capture Of Antioch

After helping Sultan Qutuz’s army to defeat the Mongols at Ain Jalut, Baibars decided that he had had enough of taking orders. On the way back from the battle, soldiers loyal to Baibars assassinated Qutuz and proclaimed their loyalty to the new sultan. With this, Baibars became Baibars I, the Mamluk sultan of Egypt and Syria. Between 1265 and 1271, Baibars, a devout Muslim who believed in violent jihad, began attacking the last Crusader towns and villages in Syria and Palestine. Baibars’s Mamluk soldiers soon became the rulers of Christian coastal cities like Arsuf and Jaffa. In 1268, the Mamluks began their devastating siege of Antioch, the last Crusader state still standing in the Holy Land. Although the Christians fought bravely until the bitter end, the city ultimately fell to Baibars. Once inside the city’s walls, Baibars oversaw a grotesque slaughter of the population. According to French historian Rene Dussaud, Baibars turned the once-thriving metropolis into a glorified village. By 1271, Baibars’s army had captured the last Crusader castles in the Middle East, including the majestic Krak des Chevaliers. Due to these victories, Baibars became a great Muslim hero. For the Christians, Baibars became the personification of evil. Whatever the perspective, it is undeniable that Baibars was the man who forever ended the dream of the Crusaders.[8]

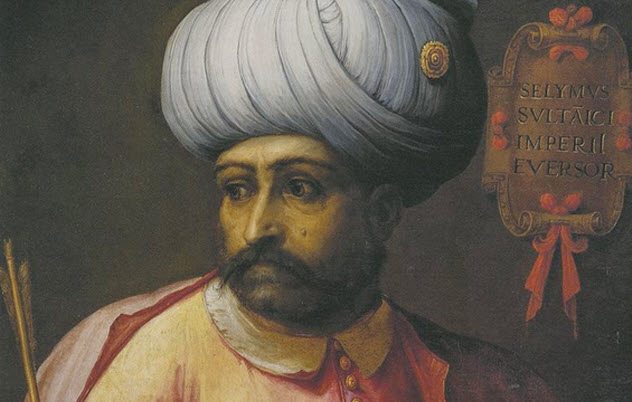

2 The War Against The Ottomans

Despite sharing a common Turkic ancestry, the Ottomans and the Mamluks were bitter enemies during the 15th and 16th centuries. For the Ottomans, the Mamluks stood in the way of their plans to unite the entire Sunni Muslim world under one caliph. For the Mamluks, the upstart Ottomans had no right to lay claim to the Mamluk lands of Egypt and Syria. The first war between the two powers began in 1485. During that decade, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror had already achieved great victories against European Christians at Rhodes and Otranto. Mehmet also had designs on conquering all of southern Italy and giving direct military aid to the rebellious Muslims of Granada. However, by 1481, Sultan Bayezid II was in control of the Ottoman Empire, and he was nowhere near as capable a military commander as his father. The first Ottoman invasions of Mamluk-controlled Anatolia and Cilicia ended in stalemates. Out of fear of the Ottomans, King Ferdinand II of Aragon, Castile and Leon, and Sicily formed a military alliance with the Mamluks. This meant that the Mamluks enjoyed a steady supply of Spanish foodstuffs and weapons until the war ended in 1491. One year later, the Nasrid dynasty of Granada surrendered to the Spanish crown because they could not rely on Ottoman support. This ended the “Reconquista” of Spain and Portugal.[9] Between 1516 and 1517, the Ottomans fought another war against the Mamluks. This war would prove to be decisive for the Ottomans. Under the command of Sultan Selim I, Ottoman armies captured Aleppo, Palestine, and, ultimately, Cairo. This war ended the Mamluk dynasty of Egypt and brought most of the Muslim world under the yoke of the Ottomans.

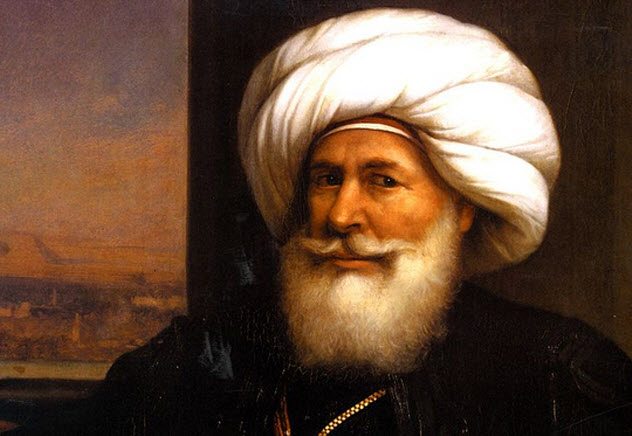

1 Battle Of The Pyramids And Egyptian Independence

Despite losing their sultanate in Egypt, the Mamluks remained a powerful force in the politics of that country. The Ottomans actually kept the Mamluks around and incorporated them into the Ottoman army. Even as late as 1798, a Mamluk bey, or military chieftain, was still in control of Egypt. This time, though, Murad Bey had to answer to Ottoman authority. In 1798, the brilliant French military general Napoleon led his army into Egypt and captured Cairo. The goal of this move was to seize control of the Red Sea and the wealth of Egypt to fund Napoleon’s military campaigns in Europe. Only about 25,000 Mamluks defended Alexandria and Cairo and put up very little resistance. Although the Battle of the Pyramids turned out to be a military embarrassment for the Ottomans, Napoleon failed to maintain power in Egypt thanks to the involvement of the British Royal Navy. Ten days after taking Egypt, Napoleon’s navy was handily defeated by Admiral Horatio Nelson during the Battle of the Nile. Napoleon’s brief victory in Egypt exposed the fact that the Ottoman military and government in Cairo was in the firm grip of the Mamluks, many of whom were tired of fighting on behalf of Istanbul. By 1805, Ottoman Egypt was all but officially independent thanks to the administration of Muhammad Ali, an Ottoman viceroy of Albanian extraction. Muhammad Ali went on to found the royal dynasty that ruled Egypt until 1952. Muhammad Ali’s creation of the antonymous Khedive of Egypt would never have happened without the aid of Mamluk soldiers and Muslim mercenaries from the Balkans.[10] Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Boston. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet