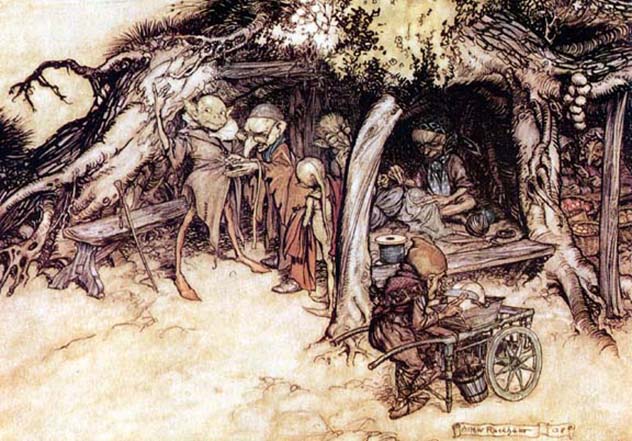

10Iceland’s Elves

When the Icelandic Road and Coastal Administration set about completing a road that would help connect the Alftanes peninsula with the rest of the country, groups were outraged. Part of the problem was environmental, with some saying that the road was going to destroy bird habitats and not a few of Iceland’s most beautiful lava formations. But another huge part of the outcry was on behalf of Iceland’s oldest native creatures: their elves. Even then, in 2013, the elves came first for countless people who had grown up with stories of just what happens when you cross them. The voice of the people’s protest was led by a seer and elf garden owner-operator named Ragnhildur Jonsdottir. Jonsdottir claimed—among other things—that one of the largest rocks that was slated to be demolished for the road was an elf church. How does she know this? Because she could see it and sense it, having a connection to the elves that many Icelanders also claim. The problem was compounded by the idea that all elf churches are connected, and destroying one would set off a disastrous chain reaction. Jonsdottir is not alone in her beliefs, and in 1998, a survey suggested that around 54% of people believed in elves and their power to do good or evil. Protests against building projects made on behalf of elves are so common that the government has a 5-page “standard reply” that they issue when the debate comes up. In the 1970s, a road-building project was stopped because it supposedly went through an elf area, and since then, it has been said that the elves now protect those in the area. They protect those in other areas, too; In 2010, a former member of Parliament walked away from a major car accident with only superficial injuries, and later found out about a belief that there were a group of elves living in a nearby boulder. After consulting with them through Jonsdottir, they accepted his offer to be moved to a safer location in a sheep field near his home. The debate over the new Icelandic road was no short-lived argument, either. The Icelandic Supreme Court got involved in 2013 to listen to the arguments for the church—which was said to be the legendary church Ofeigskirkja. It wasn’t until March of 2015 that the matter was settled with the moving of the 70-ton “church”. Jonsdottir reported that the elves were happy after being given a year and a half to prepare for the moving of their church, and noted that they were usually more than happy to comply with a request that would benefit their human neighbors.

9Washington State’s Bigfoot Protection Ordinance

Bigfoot might be the most well-known of all the crytids, the ape-like, man-like creature that has proven incredibly elusive in spite of all the attempts that have been made to find him. The earliest references to Bigfoot date back to the 1840s when a missionary named Elkanah Walker published a story about a creature that he named after a Native American word that was anglicized as “Sasquatch”. According to the stories, they live primarily in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, and Washington State has issued several ordinances that makes killing them a crime. In 1969, Skamania County passed the County Ordinance no. 69-01. The law was based on the possibility that the legends, sightings and footprints really did come from an actual creature, along with the idea that a huge number of people head out into the woods every year to try to find definitive proof that the creature exists. Those people, the one-page document explains, are most likely armed and well aware that the only concrete evidence that might convince skeptics is a corpse. That makes them a danger to not only the obviously endangered Sasquatch, but also to other innocent hikers and travelers exploring the county’s wilderness for reasons completely unrelated to cryptids. So the ordinance made killing Bigfoot a felony that carried a sentence of no more than a $10,000 fine and five years in jail. Even though it was adopted on April 1, it is easy to see why the ordinance is a good idea as it discourages people from heading into the woods armed to the teeth, and might well prevent human casualties of over-zealous Bigfoot hunters. Skamania’s ordinance was amended in 1981 (to a $1,000 fine, a year in jail and a misdemeanor, as the county didn’t actually have the authority to declare the killing a felony), and in 1991 Whatcom County issued a similar ordinance. Both laws came on the heels of a renewed interest in Bigfoot; in Skamania County, the fervor was started by the release of the now-famous footage of a Bigfoot walking along a Northern California Creek. The influx of Bigfoot hunters that hit Whatcom County coincided with the Mount Baker Foothills Bigfoot Festival, which sadly no longer runs.

8The Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary

The Sakeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Bhutan is an incredibly beautiful, remote area of the little country that is recognized by UNESCO as the Paradise of the Rhododendrons and for its threatened species. It is home to the red panda, the musk deer, the Himalayan serow, and the Himalayan black bear, along with 147 types of birds. If the stories are to be believed, however, there is another creature in the reserve far more endangered than any other: the migoi, the Himalayan version of the yeti. The sanctuary was set up to protect the mythical migoi, using a $700,000 grant given to Bhutan’s government by the MacArthur Foundation. The migoi isn’t your traditional Bigfoot. According to the legends and lore, the creature stands around 8 feet (2.4 meters) tall and has been known to evade trackers by walking backwards in its own footprints. It can also make itself invisible, a handy ability that is used to explain why it is so elusive. The few glimpses people have been able to catch of the creature happened in the area that is now the Sakeng Wildlife Sanctuary, which was officially designated a protected area in 2003. The sanctuary is also home to a group of native people called the Brokpas, one of the handful of isolated groups that still resist contact with outsiders. The group are a semi-nomadic people who rely on their yaks for survival, following the animals to grazing lands when the conditions are harshest and returning home when the climate becomes, at least temporarily, more bearable. They have developed their own distinct culture, complete with songs, ballads, and something called the yeti dance. That all makes the sanctuary just as valuable for them as for the legendary migoi.

7The Storsjo Lake Monster

The oldest mention of a monster living in the depths of Sweden’s Storosjon (Great Lake) date back to 1635. Since then, there have been hundreds of sightings and in 1894, one Swede even set up a stock company whose main purpose was the capture of the lake monster. Descriptions are all over the place, with some claiming the beast has three humps, that it is anywhere from 9 feet (2.74 meters) to 50 feet (15.25 meters) long. It has been described as having a dog-like head with fins. It has been yellow, red, black and grey, and some claim it makes a wailing sound—or a rattling sound—when it surfaces. In 2008, cameras installed underwater seemed to show the silhouette of something that believers called the mysterious lake monster. The footage was captured in the village of Svenstavik, and its reported success was followed by the establishment of an Observation Station. The Storosjon lake monster has enjoyed a protected status for some time, but in 2005 a government watch group decided to step on everyone’s fun by condemning the 1986 law that made the monster an endangered species. The law—which would have protected the creature from hunters that would try to prove its existence by killing it—was revoked in 2005. According to those who took a stand against the law, there was no way to prove the monster was real and, therefore, there was no way that it should be considered an endangered species. There are still plenty of people who believe, especially with the new video evidence that seems to prove there is something living in the depths of the Swedish lake.

6Canada’s Motion to Protect Bigfoot

In 2005, a video from Manitoba went viral when it was claimed that the out-of-focus creature hanging out on a riverbank was the elusive Bigfoot. A few months later, a tuft of hair was found in the Yukon after residents rushed to investigate what sounded like a huge animal moving through the brush. Even though it turned out to be another false alarm (it was bison hair,) the renewed interest in Bigfoot led one Canadian Parliament member to campaign on the cryptid’s behalf. Bigfoot believer Todd Standing took a petition to Parliament member Mike Lake, appealing for legal protection to be issued to all members of the Bigfoot species. Standing claimed to have absolute, definitive proof that the elusive cryptid was real, but that he wasn’t going to be sharing it with anyone until he was certain they were going to receive all the protections of any other endangered animal species. In turn, Lake took the petition to Parliament and almost immediately issued a statement that not only did he not actually endorse the petition as much as present it, but that he felt it his duty to represent the interests and opinions of his constituents that took the time to make sure all their documents were in order. His press release also stated that the motion to afford Bigfoot legal protection had been tabled. As for Todd Standing, his professed evidence still hasn’t come to light. In 2014, he was appealing for help from a geneticist to perform DNA testing on a piece of hair that he was convinced belonged to Bigfoot, in spite of previous lab findings that said it was simply human hair. New videos of Bigfoot in the wilderness were uploaded in 2015, but Standing still has to convince Canada that they need protecting.

5Ireland’s Leprechauns Get EU Protections

There are a few things that are quintessentially Irish, like Guinness, ancient standing stones and, of course, leprechauns. But things have changed in Ireland, and according to one man who claims to be one of the few that are still capable of talking to the leprechauns, there are now only 236 of them left. Kevin Woods—better known to locals as McCoillte—was granted his unique gift after he found a few gold coins left behind in a Carlingford, Couty Louth wall. According to the story, it was a man named P.J. O’Hare who found four gold coins, a little leprechaun suit and some bones in 1989. He kept the bones and the suit and put them on display at a local pub (where they still reside), but the coins went missing when he died. According to the story, McCoillte had been repairing a stone wall when he found the coins that his old friend had left behind. He kept them for years, not really giving much thought to the whole thing, until one day when he was out walking his dog. They came across three leprechauns sitting on a rock and talking when they were transfixed, unable to move. The leprechauns took no notice of them, and it was only when they went on their way that the spell was broken and McCoillte could move again. Even though his wife didn’t believe his explanation of where he’d been all day (it was 8 p.m. by the time he returned home), McCoillte knew that he had to start campaigning for the protection of Ireland’s few remaining leprechauns. The resulting campaign led to the 2009 European Habitats Directive that designates the entire area as a protected sanctuary for the local flora, fauna, and leprechauns—all 236 of them. McCoillte and his family are still there, too, escorting curious visitors through the local Leprechaun Caverns, telling the story of the evolution of their folklore from the Druids and the Vikings, through the invasion of the Normans and into modern times.

4Mermaid Ivory

While skeptics and cynics might think that issuing a protected status for a mythological creature or a crytpid is a bit silly, the idea of protecting so-called “mermaid ivory” is a little different—even though there are a number of people who think that the protection of a creature that doesn’t exist anymore needs to be implemented. The Stellar’s sea cow has been extinct for around 250 years, gone long before we developed the idea of protecting endangered species. Since they died out before laws were passed, that makes it perfectly legal for people to sell carvings and other trinkets made from their bones. They’re frequently marketed under the partially deceptive name of “mermaid ivory”, while similar trinkets made from the bones of walrus are often called “mermaid bone”. The problems really started when samples of mermaid ivory were tested. Pieces that were from St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Strait—well out of the known range of the Stellar’s sea cow—tested as being from individuals who died there around a thousand years ago. And some pieces sold as mermaid ivory have been proven to be not Stellar’s sea cow at all, but gray whale and various types of endangered dolphins. Those animals are, of course, protected by law. Specifically, they’re protected under the Maine Mammal Protection Act, and while the native people of St. Lawrence Island are allowed to hunt a certain number of the protected animals on a subsistence basis, selling pieces and products made from the animals that are killed during their hunts isn’t allowed. The professor that did the DNA studies that determined not all mermaid ivory comes from an extinct species notes that while those that are doing legal hunting don’t seem to be the ones making a profit from any illegal sales, she does say that extending legal protection to a species that hasn’t existed for centuries might help protect species that are in danger today.

3Protecting Nessie

Britain’s Tory government used one of the country’s most famous icons in order to give a rather exotic, mysterious face to some serious legislation. The inquiries started with the Swedish government, who were looking to find out how Scotland was dealing with their lake monster. The inquiries resulted in the afore-mentioned protection given to the Storsj lake monster, but the idea didn’t go unnoticed in Scotland, either. A series of tongue-in-cheek memos raised concerns that since Nessie couldn’t be classified as a freshwater fish, the Salmon and Fisheries Protection (Scotland) Act of 1951 wouldn’t apply to her. In the end it was decided that there was at least one law that did apply to her: the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act made harming Nessie—and the country’s other protected species—illegal. Five decades earlier, Nessie’s local MP Sir Murdoch MacDonald had penned a letter suggesting that he was going to appeal for legal protection for her. The seemingly odd request made a lot more sense with the discovery of some of the most bizarre documents in Scotland’s recent history. In 1933, Scotland opened an official file on Nessie’s activities and the activities of those that were looking for her. A series of documents and correspondence only uncovered in 2014 told the bizarre story of a London-based National History Museum academic who put out a call for monster hunters. They wanted Nessie and they wanted her dead, mounted and displayed at the museum in London. McDonald had gotten wind of the plan and requested that a bill be put to Parliament to protect Nessie from English trophy hunters that wanted to catch and kill her for the museum. Inquires found that there was no protection for “Monsters” and “great fish”, and if they wanted to keep Nessie from ending up in an English museum, something needed to be done. While no new legislation ultimately resulted from the proposition, it was later decided that Nessie was protected by the 1912 Protection of Animals Act, which states that it is illegal for any person to do anything to an animal that would result in it coming to harm.

2Protecting Champ

The stories of the monster that lives in Lake Champlain date back to the local Iroquois and Abenaki. Even though Samuel de Champlain is usually credited as the first European to see Champ, he did record some of the tales he was told about the mythical monster. He was told that the beast resembled a pike, but was protected by a skin so thick that no weapon could pierce it. In 1819, a sighting from Bulwagga Bay seemed to cement the idea that there was something terrifying living in the lake, and over the next few centuries, hundreds of people would claim to have spotted Champ. Champ’s hide was also on the wish-list of P.T. Barnum, who offered a $50,000 reward to anyone who was to bring him the supposedly indestructible skin so he could add it to his exhibits. Not everyone has taken to the idea of catching Champ, and Port Henry spearheaded a campaign to protect the monster. In the 1980s, they proposed—and passed—legislation that declared the waters off the coast of Port Henry a safe haven for Champ. Their laws were echoed by similar legislation passed by the State of New York and the State of Vermont, making Champ a protected creature. In April 2014, Port Henry went a step further. Based on the musing of crytptozoologists that have suggested Champ is a plesiosaur left over from the days of the dinosaurs, the mating season of Champ and his (or her) associates would likely be in the spring months. Following a decrease in Champ sightings, the Port instigated a ban on fishing from April 15 to June 29 to allow Champ and company to have a little alone time that will hopefully keep the species going. The fishing ban turned out to be an April Fools’ joke, but the other legislation is very real.

1The State Where You Can Kill Bigfoot

While most of the aforementioned legislation is of a protective nature—either for the cryptids in question, the people who are looking for them, or the other endangered species they share their territory with—there is one notable exception. In Texas it is perfectly legal to kill Bigfoot. It started with an inquiry to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, asking about the legalities of capturing or killing Bigfoot. Their response, written by L. David Sinclair, states that as far as Texas was concerned there are no limits on their killing or capture. Bigfoot’s official status is as a non-protected animal, and that means that he can be hunted anywhere (with consent from a landowner if necessary) and during any season. There are also no limits on how many Bigfoots you can take home, either. Bigfoot is considered an exotic, non-indigenous animal to Texas—in other words, he is an invasive species. Texas has considerable problems with invasive species, like feral hogs, and the resulting laws state that you can pretty much kill as many of them as often as you like. The Gulf Coast Bigfoot Research Organization (GCBRO) has tracking and ultimately killing a Texas Bigfoot as one of its core goals, claiming to be the coastal area’s first line of defense against Bigfoot. Featured on a Discovery Channel show in 2014, their goal—coming home with the dead body of an adult male Bigfoot—wasn’t to be fulfilled, and not everyone was thrilled about their mission. While there is also a debate over just how sentient and human-like Bigfoot is—and whether or not killing one should be considered murder—there are also people that aren’t thrilled by the idea of zealous hunters wandering around the countryside: the exact thing the Washington State legislation was hoping to stop. Read More: Twitter