Now, a little more than 40 years later, we do have the technology to rebuild human beings—or parts of them, at least. As these ten bionic innovations that could change medicine indicate, it may not be much longer before we can completely “rebuild” injured men and women.

10 Eye

As a result of age-related macular degeneration, British pensioner Ray Flynn lost his ability to distinguish faces in 2009. His quality of life improved drastically in 2015, when he received an electrical implant that transmits a video feed to healthy cells in his retina. A tiny camera attached to his glasses captures the video. He can now recognize faces again as well as read. He can see his TV more clearly, too. Most amazing of all, he can see even with his eyes closed, thanks to his video glasses.[1] People suffering from retinitis pigmentosa have been assisted by the same technology that helps Flynn to see. Ophthalmologist Paulo Stanga of the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital said, “This technology is revolutionary and changes patients’ lives—restoring some functional vision and helping them to live more independently.”

9 Ear

In some cases, gene therapy may work with bionic technology to improve hearing. Most hearing loss takes place between the hair cells in the cochlea and the auditory nerve. Cochlear implants alleviate this by simulating the auditory nerve with tiny electrodes. However, when auditory nerves are damaged, the signals sent by the electrodes must be stronger, which muddles the resulting sound. The only way to refine the sound is to repair the auditory nerves. That’s where gene therapy comes into play. In tests, such therapy has caused “shriveled” auditory nerves to regrow. More specifically, Jeremy Pinyon, an auditory scientist at the University of New South Wales, and his team administered a gene-encoding neurotrophin, a protein which stimulates nerve growth, to cells in the inner ears of deaf guinea pigs. This resulted in auditory nerve regeneration, allowing the animals to hear again. Although the procedure won’t be ready for clinical use for some time, it shows promise as a way to produce bionic ears enhanced through gene therapy.[2]

8 Teeth

The ability to regenerate teeth and prevent cavities using bionic technology is possible in the near future, as dentists use bioactive replacements to battle tooth decay. Dr. Ana Angelova Volponi says research toward creating such “bioteeth” has made big advances by using adult gingival stem cells. Although the development of bioteeth may be possible, experts differ on the practicality of growing teeth as a routine dental practice. However, research continues, some of it involving 3-D printing, in the hope that, in the future, we’ll be able to grow replacement teeth.[3]

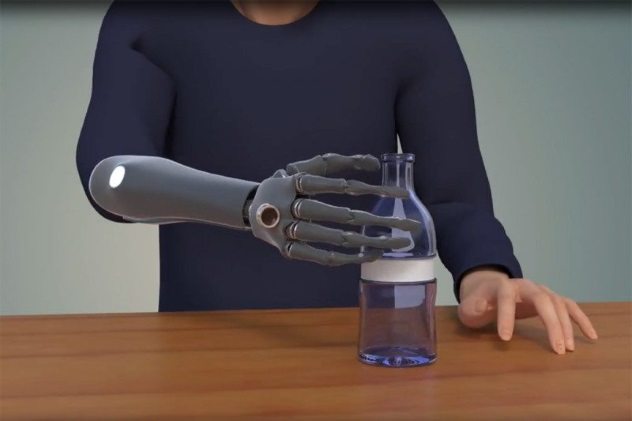

7 Hand

The 2006 movie Pan’s Labyrinth introduced a character with eyes in the palms of his hands. Although the movie is a fantasy, a bionic hand equipped its own artificial eye is a fact. The prosthesis uses artificial intelligence to “see” objects. The wearer’s intention to pick up an object is relayed, as electrical impulses, to the hand. The hand responds by taking a picture of the object. Then, using “one of four possible grasping positions,” the hand closes on the desired object, lifting it. Pictures of over 500 different objects were used to train the hand. Each was shown in 72 images to indicate various angles and to display various backgrounds. As tests progressed, the hand learned which grasping position worked best for each object. Presently, the hand is a prototype, although it’s been tested by two amputees, with 90-percent effectiveness. Before it can be put into service, it must attain a success rate of 100 percent. Researchers hope new algorithms will enable them to reach that goal. They also plan to make the hand lighter and to put the camera in its palm, instead of on the back of the hand.[4]

6 Pancreas

The bionic pancreas created by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston University measures blood sugar automatically, releasing insulin as needed. A sensor implanted under the skin monitors blood sugar in the wearer’s tissue, uploading data to an iPhone application. Every five minutes, the app calculates the amount of insulin needed, supplying it through a pump. There’s no need to determine the carbohydrates consumed in each meal and input the quantity into the device. Instead, wearers indicate whether the meal was “typical,” “more than usual,” “less than typical,” or a “small bite” as well as whether it was breakfast, lunch, or dinner. A test of both adult and adolescent diabetics showed that the participants’ blood sugar was healthier when they used the bionic pancreas instead of their usual treatments. After further tests, the bionic pancreas may provide a new way of monitoring and controlling blood sugar levels in diabetic patients.[5]

5 Leg Brace

When he was two years old, John Simpson, now in his sixties, fell and cut his chin. As a result, he contracted polio, which left him unable to walk without a leg brace. The brace was cumbersome and limited in function. “For as long as I can remember,” he says, “I’ve had to walk with a locked-knee steel caliper which I had to manually adjust whenever I wanted to bend my leg. If that malfunctioned, I broke my leg.” His new bionic leg brace, however, has given him freedom. With it, he can walk, ride a bicycle, and climb stairs. The device has “revolutionized” his life, he said. Employing Bluetooth technology, the computerized bionic brace, using sensors on Simpson’s thigh, monitors his steps, moving with him. The carbon-fiber brace is stronger than steel and operates on a rechargeable battery. The bionic brace checks the knee’s position every 0.02 seconds, giving Simpson the flexibility he needs but lacked with his previous brace.[6]

4 Knee

Hailey Daniswicz flexes the muscles in her thigh. Electrodes send signals to a computer. On a monitor, an avatar bends its knee. The young woman lost her lower left leg to cancer. Once the computer has been calibrated to “recognize slight movements of her thigh,” she can be be equipped with an bionic leg which she controls naturally. According to project leader Levi Hargrove, a research scientist at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago’s Center for Bionic Medicine, the goal is to “integrate the machine with the person.” The prosthesis uses electromyography (measuring muscles’ electrical activity) and pattern recognition software. Nine electrodes, each attached to a different muscle, detect electrical signals sent from the nerves to the muscles. The computer recognizes signal patterns and determines whether she wants to bend her knee or flex her ankle. Daniswicz and the program’s three other test subjects could not only move their legs and bend their knees, but they could also control their ankles using the bionic knee. Over two million people have had their lower legs amputated, and twice as many are predicted to undergo such an operation by 2050, due to an increase in diabetes. Currently, prosthetic legs rely on their wearers initiating the legs’ movement by swinging them. It’s hoped that new bionic knees and limbs will revolutionize these prostheses in the future.[7]

3 Ankle

According to Hugh Herr, director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Biomechatronics group, “Technology is marching forward at such an accelerated pace that we can easily imagine many disabilities that exist today no longer being disabilities.” Bionic limbs are one of the applications that can restore lost abilities to handicapped people. Adrianne Haslet-Davis is an example. A professional ballroom dancer, she lost part of her leg in the Boston Marathon bombings. Herr, who lost his own legs in a climbing accident, built an artificial ankle that restored Haslet-Davis’ dancing ability. “In this lab, we steal from nature,” Herr explains. “We model the body part that’s missing and we model the muscles and how the muscles are controlled by the spinal cord and from that science we extract principles that dictate how the mechanics are designed.” Herr’s team has supplied 90 amputees with custom-made versions of the bionic ankle. The Veterans Administration, the Department of Defense, and some private insurance companies bore the cost of the ankles, but in the future, Herr hopes the high-tech prosthesis will become more widely available for those who need them.[8]

2 Exoskeleton

Advances in bionic technology have resulted in the development of a bionic exoskeleton. Worn over the body, the exoskeleton helps its wearer to walk. Kevin Oldt injured his spine in a snowmobile accident. As a result, he was dependent on a wheelchair. Now, with his exoskeleton, a harness-like device combining an assortment of struts, sensors, straps and software, he receives assistance specific to his needs. Once Oldt starts to walk, aided by crutches, the exoskeleton’s four electric motors straighten his lower body. His legs work with the exoskeleton, as the latter measures the amount of force he generates as he raises his foot, pushing against the floor. In April 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the Ekso GT exoskeleton that Oldt uses for stroke patients and people with spinal injuries below the neck.[9]

1 Tail

It’s not often that a person needs a tail, but the special effects team for the Lord of the Rings movies provided Nadya Vessey of Auckland, New Zealand, with one so that she could take a swim. A congenital condition prevented her legs from developing properly, and at age 16, they were amputated. When Vessey was 50, a young boy, seeing her remove her prosthetic legs, asked her what had become of her own legs. She told him she’s a mermaid. Inspired by her explanation, she wrote to Oscar-winning Weta Workshop, the special effects company that also created visual effects for The Chronicles of Narnia and King Kong, asking them to make her a mermaid’s tail. They responded by building her such a tail from wet suit fabric and plastic molds. The tail’s structure enables her to swim in graceful, undulating movements like those of the mythological creature she resembles when wearing the prosthesis. The tail is custom-fit for Vessey, complete with a polycarbonate spine and tail fin as well as digitally printed scale patterns. The loss of her legs notwithstanding, Vessey competed in high school swimming, and she hopes to use her bionic mermaid’s tail to compete in a triathlon’s swimming event.[10]