10 Hopi Sentenced To Alcatraz

First discovered by the Portuguese and the Spanish in the 1540s, Alcatraz had already been inhabited for at least 10,000 years. By the time the Spanish came to the area, there were about 10,000 individuals settled in the Bay Area around the island. According to tradition, the island had long been used for exactly the same purposes it later was—isolating people who had broken a law. In 1894, the Hopi were in the middle of a rebellion against government regulations, which stated that they needed to send their children away from home to attend government-run schools. In order to force the children to go, it was first suggested that the military and law enforcement be sent in to arrest anyone who wasn’t sending their children away. When bad weather and snows made that impossible, it was decided that they’d interrupt the supply of goods and food instead. It was a completely legitimate strategy, as far as the law was concerned. According to the Rules for Indian Schools of 1892, food and other necessities could be taken away to force compliance. When that didn’t work and the Hopi still refused to send their children to government schools, 18 tribal leaders were arrested and put on trial for their refusal. Found guilty, they were sentenced to Alcatraz. Those left behind still refused to comply with government orders, and when the original leaders were released a year later, they continued their nonviolent protests against the educational restrictions. With the resistance leaders unwilling to resort to violence, the government-sanctioned development of schools continued. In the 1960s and 1970s, members of the Sioux and Mohawk, along with a group going by the name “Indians of All Tribes,” occupied Alcatraz in order to demand that the island be returned to those who had been there first. They didn’t win the island, but they did succeed in bringing attention to problems that had gone unaddressed for too long.

9 Black Mesa

Black Mesa is in northern Arizona, and it’s huge. The coal fields cross both Hopi and Navajo reservations, and in 1909, an incredibly brief survey of the area would determine that there was a huge amount of potential resources that could be exploited. The area already had an operating mine, and the coal was being used on the reservation. By the end of World War II, the country was looking for some ways to maximize use of their own resources, and that included coal. In 1943, the Navajo attempted to increase their mining operations in the area, recognizing what they were sitting on for what it was—cash. At the time, they were an extraordinarily poor nation, relying on an income from the Bureau of Indian Affairs for support, so they entered into an agreement with the Interior Department. Coal was selling for $4.40 per ton, and in a typical deal, $1.50 of that would be going to the owner of the land. That was the basic price, though it’s absolutely not what the government offered the Navajo and the Hopi; they got $0.17 per ton. There was also no provision in the contract to renegotiate prices should the price of coal go up, and it did. By the time the country was in the middle of the 1970s oil crisis, coal was $15 a ton. The tribes whose lands were being mined were still receiving $0.17. To add insult to injury, the tribes, who had seen little choice but to agree to the contracts and allow the government to come in and start mining, had their hands tied when it came to how the mining was done. In the early 1970s, the mine was putting out about 1 million tons of coal each year, and the process was likened to tearing down St. Peter’s Basilica for the marble. It wasn’t just environmental groups that leaped on the companies for their strip mining processes; the tribes absolutely weren’t happy with the complete destruction of ancient sites.

8 The Termination Of The Menominee

A huge amount of US dealings with various tribes across the country has involved some absolutely audacious attempts to integrate them with what’s considered more mainstream American society. Beginning in the 1940s and continuing into the 1960s, there was a policy put in place that was ominously called Termination. In the 1930s, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs had been a man named John Collier, who had given the different tribes nothing less than the right to keep their own culture. When he left office in 1945, those that hadn’t agreed with him took the opportunity to reverse everything he’d done. The Termination policy was touted as an emancipation process that would free tribes from the control of the government. What the policies were really doing was taking away the power for tribal governments to run themselves. Reservations were to be broken up and no longer receive any kind of government protection. In turn, groups that had previously been run by their own, generations-old system of governance would now be answering to the same rules and institutions that European Americans did. The process was a long one, and it required legislation to be drawn up for each individual tribe. One of the first was Wisconsin’s Menominee Tribe. In 1954, they were officially terminated, and Congress declared that they would no longer be recognized as a tribe. The council was told that they would be terminated whether they liked it or not. Several extensions were granted, but eventually, in 1961, they were terminated. The fallout was fast. Programs that had been supported by the federal government before, like schools and hospitals, didn’t have a funding base. The small population couldn’t afford to support things like utility services on its own, and termination, bizarrely, meant the removal of government funding that small towns all over the country rely on to survive. Hospitals and clinics closed, courts were shut down, police departments dissolved, utility services were shut down, and suddenly, the people needed to pay for hunting and fishing licenses for the land that had sustained them for thousands of years. Termination was repealed in 1973, largely due to its disastrous results with the Menominee, but the damage was already done. The tribe had been living in the same area for more than 10,000 years and were so closely tied to the land that they took their name from the Menominee River, where their origins were set. Before termination, they were one of the wealthiest tribes in the country, completely self-sufficient with their own government, law enforcement, and schools. Fifty years later, the Menominee are reincorporated as a tribe, but they’re still picking up the pieces.

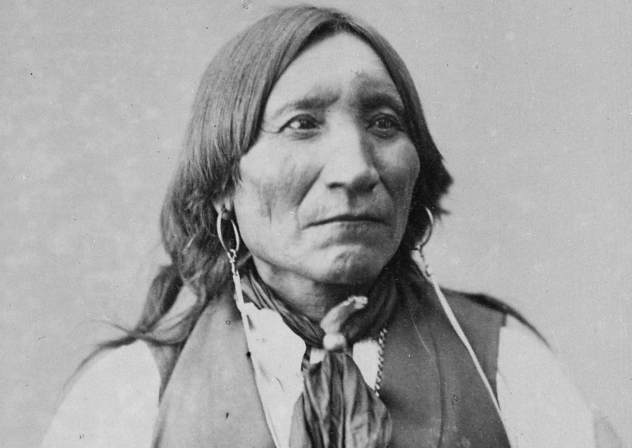

7 Lone Wolf vs. Hitchcock

By the turn of the 20th century, many tribes had been forcefully removed from their ancestral lands and forced onto reservations. An 1867 treaty called the Medicine Lodge Treaty appeared to give tribes at least some sort of say in what happened to the lands that they had been forced onto. In theory, the treaty said that in order for reservation land to be made available for other uses, a three-fourths majority approval needed to be given by the tribe that was currently on the land. In 1900, though, the government decided to parcel off the land that had been given to the Kiowa-Comanche tribe. Those that accepted a specific plot of land were also given citizenship with it, and the extra land was also parceled off—to be sold to anyone, even though no approval was given. Kiowa leader Lone Wolf sued the government for breach of treaty, and he lost. The verdict given was that Congress had the right to change absolutely any previous treaties as they saw fit, because as the government, they had complete control over everything that went on in a reservation. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where the verdict was upheld. Members of tribes were deemed “wards of the nation,” and not long after, 50,000 settlers moved into what had been dubbed surplus reservation land. The verdict has never been overturned and is still a valid precedent.

6 The Cherokee Strip

When the Cherokee were forced to settle in an area that’s now Oklahoma, they were given about 7 million acres in three separate areas. By the 1880s, though, the country was expanding, and ranchers and settlers needed that land. The US government made an offer to the Cherokee, attempting to buy the land at $3 an acre. The offer was refused, and in 1889, Congress ordered them to sell at $1.25 an acre. The Cherokee had been making a lot of their income from leasing their land to ranchers. In 1890, though, the president signed into effect a law that prohibited all grazing after October, cutting off a huge portion of their income. After several delays, during which the government agreed to enforce the boundaries on the land that the Cherokee had managed to keep, the Cherokee Strip was opened for land claims from settlers. Somewhere around 135,000 people showed up to stand in line at the nine registration booths that were opened for registering land claims, and it went about as smoothly as you’d guess. Cavalry were called in to keep the peace, but it was a mass of fights (some drunken, some not), bribery, counterfeiting, and no small amount of heat stroke. Individual members of the Cherokee were allowed to make a run for a piece of the land that they’d previously called home, but an overwhelming majority of people who tried for land didn’t get it. And once the land had been handed out, those that did get it found that they were ill-equipped to handle it. A huge number of claims were abandoned before a year passed. Towns failed, and farms folded, adding insult to injury to those that had been forced to sell their land at a pittance.

5 The Indian Child Welfare Act Of 1978

It wasn’t until the 1970s that a big problem was brought to light, and it was a problem that people didn’t even see as a problem before that. Children were being taken from their families on a huge scale. From 1969–74, 25–34 percent of all Native American children were removed from their homes on a temporary or permanent basis and passed into the system of federal schooling, foster care, or adoption. Compare that with the non–Native American children removal rate of 5 percent. Part of the problem was the idea of federally instituted boarding schools, and we’ll look at that more in a minute. The other problem was that laws didn’t take into account the differences in tribal conditions for raising children. Generally more communal in nature, it’s perfectly normal for extended family or even neighbors to take care of children a large amount of the time. In a system that was biased in favor of families made up of only parents and children, this was seen as a problem. In states like North Dakota, about 99 percent of children removed from families were because of cases like this, which were deemed neglect cases. It wasn’t until 1978 that Congress established the Indian Child Welfare Act, which used a different set of guidelines for the removal of native children from their homes. It included a requirement for the tribal government to be involved in such rulings, added considerations for tribal customs, and, should a child still need to be removed from parent care, placement with a native family. For the first time, part of the guidelines definitely stated that maintaining family and cultural bonds was of the utmost importance.

4 The Burke Act And US Citizenship

For decades, the question of citizenship for Native Americans has been something of a weird dilemma, and the government used it as a sort of blackmail. The Dawes Act of 1887 automatically granted citizenship to any member of any tribe that left their lands and voluntarily moved away . . . except for those belonging to the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole tribes. They weren’t included until a 1901 amendment, but it was the 1906 Burke Act that was really strange and very bizarrely worded. According to the Burke Act, anyone who moved away from their tribe and accepted an allotment of land was granted citizenship, with a catch: That citizenship was withheld for 25 years or until they received special notice from government officials. Further notes in the law indicated that they not only needed to move away from their tribe but that they also needed to embrace the “habits of civilized life” before they were eligible for citizenship and all the benefits that went along with it. It was up to the Secretary of the Interior to decide if they had fulfilled their obligation to the so-called “civilized life.” Government officials were also the ones deciding whether or not people who wanted to take allotments were capable of running one. Those who received allotments and either did their 25 years or received their approval for citizenship early still weren’t in the clear; once they died, it was still up to the Secretary on whether or not their descendants were capable of running the land. If they weren’t, the land would be sold.

3 The Theft Of Geronimo’s Skull

According to the story, Yale’s secretive Skull and Bones society was responsible for robbing the grave of Geronimo and stealing his skull. For a long time, it seemed like the story would never be anything more than a rumor, until an author researching a book on Yale’s World War I veterans stumbled across a letter that seemed to prove that they had indeed stolen Geronimo’s skull. Before the leader died, he had been very specific in his wishes: He wanted to be buried in New Mexico, on Apache land. He definitely did not say he wanted his bones to be in the hands of the rich, elite members of the secret society. Yale still officially says that they don’t have the bones, but members of the society aren’t saying anything. With more than 800 of those members still around today, that makes things even more complicated. Geronimo’s great-grandson opened a lawsuit in 2009, suing both Skull and Bones and Yale for the return of the bones. The suit cites plenty of evidence, including the letter and testimony from Skull and Bones members, which confirms that inside their headquarters is a glass case containing bones that they were always told belonged to the Apache leader. The letter, dated 1918, also says that they have other bones, along with some of the tack from Geronimo’s horse. Why steal it? It’s something called crooking, a competition among the society members to see what important things they can steal for their “tomb.” Still, Yale insists that they don’t have the bones and that they have no control over Skull and Bones, while the society itself isn’t saying anything. It was only in 1990 that a law was passed to protect the graves and remains of Native Americans and to give their families rights to preserve them. In 2010, Geronimo’s family lost. According to the verdict, only thefts that occurred after 1990 are protected by the law, and the government will not force the society to return remains that had been stolen prior to that.

2 The Innocent Fun Of Grave Robbing

For the citizens of Blanding, Utah, picking up arrowheads and pieces of pottery seemed like no big deal. It was all over the place, after all, and there was so much of it that it often ended up being used for target practice. Finally, Winston Hurst, a local boy turned archaeologist, realized just what it was that people were picking up, destroying, and in some cases selling—part of the history of an entire people. In 2009, his information led to a 150-man FBI raid, along with a series of arrests. Jim Redd, a local doctor, was among those that were arrested for looting and selling antiquities; he killed himself the day after the raid. According to the townspeople, picking up artifacts was just a way of life, and according to Hurst, that’s the problem. When the mayor pointed out that there was just so much of the stuff lying around that no one had seen what the big deal about collecting—and destroying—it was, the implications were horrifying. Archaeologists like Hurst were seeing the historical record of an entire culture wiped out, and as the relic-hunting operations got larger and larger, so did the destruction. Sites around town, which were roughly 12,000 years old, were badly, amateurishly excavated. By the time Hurst had assembled a case, a staggering amount of artifacts had been looted and sold, which were later seized by the FBI. Once home to the Anasazi, the area around the town has yielded incredible treasures, jewelry, pottery, baskets, feather blankets, and other items, once left in graves as tributes to the dead. The fallout was incredible, with other suicides following the arrests, and the people who had once been his neighbors cursed Hurst as a traitor. Meanwhile, graffiti is scrawled across pueblo walls and ancient cave paintings, and offerings once left along burial sites are sold on the black market. The town, founded in 1900, was also the site of a recent sting operation in which a single agent spent $335,000 purchasing illegal artifacts over the course of two and a half years. Meanwhile, the locals whose ancestors are buried in the caves won’t even enter them, simply out of respect for the dead.

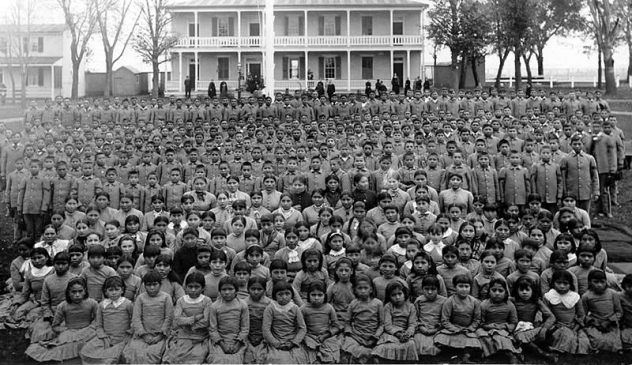

1 Assimilation Via Boarding Schools

It started in the 1870s, and in 2015, there are still people who remember being sent away from their families to attend Native American boarding schools. The programs and the idea was based on a prison program, and statements made by the man who developed that program are horrific: “All the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” That was from a speech given in 1892 by Richard Pratt. Decades later, the practice was still in place and, in 2015, there are still people who remember their mothers crying as they were taken away, being beaten for speaking in their native language, being forced to cut their hair, and being given new, Americanized names. There were around 100 boarding schools operating in the United States, and even into the 1960s, teachers there were told that their first responsibility wasn’t to educate students but to “civilize” them. The goal of the boarding schools was to take away everything that gave the students their identity. Schedules were so strict that in some cases, they were planned out in increments of five minutes, time that was precisely used for things like making beds and brushing teeth. From hairstyles and clothing to learning a new religion, they were taught everything they needed to know to not be Native American anymore. Ironically, among those that have spoken out about their experiences in boarding schools, where they were discouraged from embracing their native culture, are the Navajo Code Talkers, whose language was of unprecedented importance throughout World War II—quite a difference from their experiences in school. There are still a handful of these boarding schools in existence, but now, they have a different mission: to educate and to preserve culture. For those that still remember being torn from their families and forced to become something they absolutely weren’t, though, there’s still a lot that needs to be mended. Read More: Twitter