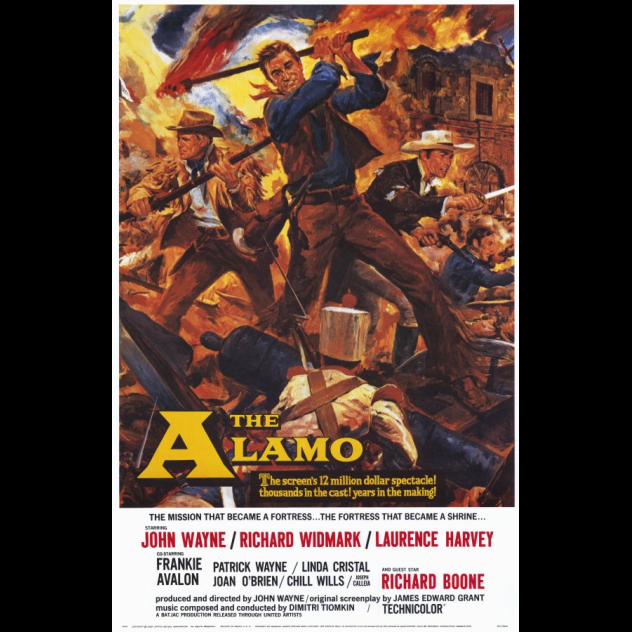

Before dying of cancer in 1979, Wayne acted in nearly 250 films, many of which were great movies with fantastic performances from the Duke. (Think Stagecoach, The Searchers, and The Shootist, just to name a few.) But while he was one of the biggest stars of his day, Wayne wasn’t content standing in front of the camera; he wanted to take a seat in the director’s chair. The Duke was especially interested in directing a film about the Alamo, the legendary mission where a small band of Texans fought to the death against a massive Mexican army. Only when Wayne finally got a chance to work on his passion project, things spun wildly out of control, resulting in one of the most disastrous film shoots in Hollywood history.

10 A Rough Beginning

John Wayne had wanted to make an Alamo movie ever since 1944. There was something about the story that appealed to his red, white, and blue way of thinking. An intensely patriotic man, Wayne admired the courage of the Alamo defenders and wanted to inspire “namby-pamby” 20th-century audiences “to stand up and fight for the things they believed in.” According to Wayne’s third wife, Pilar, The Alamo was Wayne’s way of fighting against “the faint-hearted who didn’t believe in good, old-fashioned American virtues.” In fact, Wayne so passionate about the Alamo that author Gary Wills wrote, “The closest Wayne came to having a real religion, one for which he would sacrifice himself, was his devotion to the Alamo.” Despite his patriotic fervor, getting the project off the ground proved to be incredibly difficult. In the 1940s, Wayne was under contract to Republic Pictures, and studio head Herbert Yates kept putting off Wayne’s pet project. Eventually, Wayne grew tired of the cold shoulder and left the studio to make the film on his own. A few years after he left, Yates greenlit an Alamo movie, perhaps as revenge against Wayne for leaving the company. Unfortunately, Wayne soon discovered that most Hollywood studios weren’t keen on the idea of the Duke as director. Almost every major film company turned Wayne down, until he finally struck a deal with United Artists. They agreed to release the movie, fork over $2.5 million, and give Wayne creative control, but the actor had to make a few concessions: First, he had to sign a three-picture deal. Second, he could only direct if he also starred in the film. Originally, Wayne had only wanted to appear in a cameo role as Texas general Sam Houston, but with United Artists calling the shots, the Duke agreed to don a coonskin cap and play the famous frontiersman Davy Crockett.

9 Building San Antonio

Now that The Alamo was finally on track, Wayne needed to find the perfect location to make his movie. At first, he considered shooting in Mexico, hoping to circumvent union restrictions and high wages for extras. But when a group of powerful Texans (oilmen, media magnates, and political bigwigs) learned of Wayne’s plan, they sent the Duke a rather intimidating message. If Wayne filmed The Alamo in Mexico, they’d make sure that no Lone Star institution invested in his project. Even worse, they guaranteed that the film would never play in Texas theaters. Wayne knew his Mexico plan wasn’t going to work, so he immediately set about searching for a location in Texas. And that’s how he stumbled across James T. “Happy” Shahan. A small-town rancher-turned-politician, Happy Shahan was the mayor of Bracketville, Texas, a little city outside San Antonio. Shahan owned a large piece of property that he wanted to turn into a Hollywood film set, and he began to lobby for Wayne to set up shop on his ranch. The Duke was impressed with the 22,000-acre property and agreed to shoot the film there. Now that he was filming in Texas, Wayne was able to convince all of those powerful Texas businessmen to invest in his film. As Wayne rubbed elbows with everyone from Governor Price Daniel to the publisher of The Houston Chronicle, he was also busy turning Happy Shahan’s ranch into a 19th-century “Alamo Village.” Extras were brought across the border to make over one million adobe bricks to rebuild the old town, and art director Al Ybarra set about building an Alamo replica to exact scale. Workers got busy laying electric wires and setting up a sewer system, and they even built a landing strip for airplanes coming to and from the set. Since he was doing a period piece, Wayne needed a lot of livestock. With the help of Shahan, the Duke rounded up somewhere around 1,400 horses, not to mention approximately 300 Texas longhorns. The animals stayed inside newly erected corrals, which covered around 500 acres. The crew even laid down railroad tracks so a train could drop off animal feed at the set. Needless to say, this was an incredibly expensive project. Building the sets cost about $1.5 million . . . a lot of which came out of Wayne’s own pocket. The man was so eager to make an Alamo movie that he mortgaged two of his homes, all of his cars, and even his own movie production company, Batjac. It was an incredibly risky gamble, which caused Wayne to say, “My career, my personal fortune, and my standing in the business are at stake.” According to Wayne, everything he owned was riding on this picture, including his very “soul.”

8 Casting Problems

With Wayne playing Davy Crockett, he needed to find stars to play the other two primary roles—knife-fighting adventurer Jim Bowie and military commander William B. Travis. Originally, the Duke considered both Clark Gable and Frank Sinatra for Travis, but he eventually went with British actor Laurence Harvey (best known for playing the sleeper agent in The Manchurian Candidate). Quite a few Texans were upset that a foreigner was playing their Lone Star hero, but Wayne ignored their complaints. To play Bowie, Wayne wanted future Oscar-winner Burt Lancaster, but he eventually settled on Richard Widmark (from Kiss of Death, Judgment at Nuremberg, and Murder on the Orient Express). This proved to be a rather troublesome choice, as the two men quickly came to hate each others’ guts. Perhaps it was because they were on opposite sides of the political spectrum (Widmark a liberal, Wayne a conservative), or maybe it was because Widmark didn’t respect the first-time director. Either way, the moment Widmark arrived, sparks started to fly. For example, when Widmark was hired, Wayne took out an ad in The Hollywood Reporter which read, “Welcome aboard, Dick. Duke.” But when Widmark showed up at the Alamo Village, he said to Wayne, “Tell your press agent that the name is Richard.” Wayne quickly fired back, “If I ever take another ad, I’ll remember that, Richard.” Things only went downhill from there. Another casting controversy came about when Wayne tried to pick someone to play Jim Bowie’s slave, Jethro. Singer Sammy Davis Jr. badly wanted the part in order to shake up his image, but the Texas businessmen financing the picture weren’t interested in having Davis in the film. The oilmen didn’t care for his Rat Pack image or the fact he was romantically involved with white actress May Britt. Despite all of Davis’s campaigning, Wayne eventually went with actor Jester Hairston for the role of the subservient slave, a character who’s caused a bit of debate among film fans. Wayne also hired pop singer Frankie Avalon (to win over the young crowd) and bullfighter Carlos Arruza (to bring in the Hispanic crowd). In fact, Wayne personally hired every actor and stuntman on the picture. And in addition to the cast and crew, which numbered around 342 people, there were thousands upon thousands of extras, many of whom were trucked back and forth from Mexico each day. When everyone was hired and cameras were ready to roll, over 300 people gathered on the set to bless the film with a prayer led by a local Catholic priest. They should’ve prayed harder.

7 Disaster After Disaster

Even before cameras started rolling, The Alamo‘s set was plagued with disasters. As the crew fashioned the adobe bricks necessary to build the Alamo Village, the heavens decided it was time to unleash their fury, dropping 74 centimeters (29 in) of rain on Happy Shahan’s ranch. The massive storm gave way to a flood which nearly wiped out all their work. This was just a sign of things to come. After the flood, Shahan’s daughter was involved in a nearly fatal car crash with two Alamo crew members. Afterward, the Alamo publicity office caught fire. Although actors and crew members rushed to the scene with fire hoses, they were unable to save stacks of paperwork, including payroll files and publicity materials. Things took an even nastier turn when 80 percent of the cast and crew caught the flu. It probably didn’t help matters that the set was crawling with rattlesnakes and scorpions. Not even the A-list celebrities were safe from pain and suffering. During one key scene, Laurence Harvey (playing William Travis) was standing atop the Alamo walls, looking down at a Mexican messenger. The messenger asked Travis to surrender, and the Texas commander responded by firing a cannon in defiance. However, after the cannon went off, the big gun rolled backward and crushed Harvey’s foot. Fortunately for the scene, Harvey managed to stay in character through the rest of the shot. Once the cameras stopped rolling, Harvey began to howl in pain. But instead of going to the hospital, he decided to stay on set, alternately soaking his foot in buckets of hot and cold water. This act of machismo undoubtedly impressed Wayne, but all these disasters paled in comparison to what happened to a promising young actress on the cusp of a Hollywood career.

6 The Alamo Murder

LaJean Ethridge was a member of the Hollywood Starlight Players, a small group of actors who performed in theaters across Texas. When her troupe learned that John Wayne was filming a movie in Bracketville, Ethridge and her five male co-stars got jobs working as extras. When she showed up on set, Ethridge made an impression on casting director Frank Leyva, who gave the actress a speaking role. This promotion meant that she would stay at the nearby Fort Clark with the rest of the cast and crew. As for the rest of the Starlight Players, they had to remain in Spofford, a town 32 kilometers (20 mi) away. This did not sit well with Ethridge’s actor boyfriend, Charles Harvey Smith. When it finally came time for Ethridge to shoot her scene, she did such a good job that Wayne asked her to do a few publicity shoots. He also decided to give her a bigger role and increase her salary. This made Ethridge’s boyfriend even angrier. Jealous, he demanded that Ethridge leave Fort Clark and return to their Spofford lodgings. Ethridge refused and decided it was time to ditch Smith. But after an argument, Smith stabbed her to death with a 30-centimeter (12 in) knife. As she lay dying, Ethridge’s last words were supposedly, “I love you.” Obviously, Wayne was upset by her death, but he was also worried about how the murder might affect the film shoot. After all, The Alamo was costing about $60,000 a day, so the Duke couldn’t afford to shut down production. So he simply filmed around the police investigation, but things became somewhat complicated when he received a subpoena from Smith’s lawyer to testify at an upcoming hearing. Unwilling to take any time off, Wayne actually had Texas highway patrol officers set up road blocks in an attempt to find the lawyer and change his mind about the subpoena. Eventually, Wayne was allowed to give a deposition, and he later told the press that he hoped Smith would receive the death penalty. Instead, the murderer was sentenced to 20 years behind bars.

5 The Duke Gets Frustrated

As you might expect, John Wayne was getting pretty irritated by this point. In fact, he was so tense that he was smoking over 100 cigarettes a day. The insane Texas temperatures—nearly 40 degrees Celsius (100 °F)—didn’t help Wayne’s temperament, either. The heat, combined with his old-timey costume, caused Wayne to lose around 4 kilograms (10 lb) a day in water weight. Adding insult to injury, all that sweat continually loosened the glue that held Wayne’s toupee in place. Making matters even worse, Richard Widmark and Wayne still couldn’t get along. Widmark continually dissed Wayne on set, and one evening, he showed up at Wayne’s living quarters, demanding to be let out of his contract. The Duke was eating at the time and didn’t want to discuss business. When Widmark persisted, he got into his much smaller co-star’s face and ordered him out. Eventually, the two nearly came to blows after Wayne referred to Widmark as “a little s—t.” However, after their almost violent confrontation, the two stars toned down their rhetoric. Still, Wayne was uptight for the rest of the shoot. He occasionally threw rocks at cameramen who weren’t listening up, and when a plane full of curious sightseers flew by to get a look at the set, Wayne grabbed a prop rifle and started firing blanks at the sky. Wayne’s anger eventually caused him quite a bit of embarrassment. One day while filming, the Duke heard chattering coming from behind his director’s chair. Infuriated, Wayne unleashed a volley of curse words, oaths of religious and sexual nature. But after his colorful tirade, Wayne realized that the noise was coming from a group of nuns who were visiting the set that day. Needless to say, Wayne apologized, but as uncomfortable as things were, the situation would become even worse.

4 Enter John Ford

Draw up a list of the greatest directors of all time, and John Ford would definitely make the cut. A four-time Oscar winner, Ford has influenced everyone from Steven Spielberg to Akira Kurosawa. He was also the man largely responsible for making John Wayne a star. Ford picked the Duke for his breakout role in Stagecoach, and he later directed Wayne in classics like The Searchers, The Quiet Man, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Wayne felt incredibly indebted to Ford, and he treated the old director like a father. But Ford was an abusive dad. The eye-patched filmmaker was something of a sadist who regularly assaulted his actors, both verbally and physically. And despite his physical stature and commanding attitude, Wayne often took the brunt of Ford’s abuse . . . and he took it quietly. So when Ford arrived on the set of The Alamo, Wayne was filled with mixed emotions, especially when Ford tried to commandeer the movie. As soon as he showed up, he began telling Wayne how to shoot his scenes. And if things didn’t play out to Ford’s liking, he would shout, “Do it again!” When Wayne asked why, Ford would holler, “Because it was no damn good!” On one occasion, Ford even told an actor to wear his hat a certain away. The actor protested, saying Wayne had given him different instructions. Ford, being Ford, snapped, “Oh, what the hell does he know about that stuff?” Wayne, ever the dutiful protege, had no clue what to do. True, the Duke wanted sole director’s credit, and he didn’t want people claiming that Ford was the man really pulling the cinematic strings here. But Wayne didn’t have the heart (or the guts) to order Ford off the set. Instead, Wayne came up with a clever idea to get the old man out of the way. He spent $250,000 to give Ford his own second unit to film battle sequences . . . far away from the main action. Historians dispute how much Ford’s second unit actually contributed to the picture. According to some accounts, Wayne didn’t use any of Ford’s footage, a move which angered the old director. But according to writer Scott Eyman, Ford was responsible for 10–15 percent of the movie. Either way, Ford agreed to give a little blurb for the film, boldly proclaiming that The Alamo was “the most important picture ever made.”

3 Russell Birdwell, PR Man

Originally, John Wayne expected The Alamo to cost around $5 million, but with all the extras, costumes, animals, and sets, the budget eventually ballooned to somewhere between $10–12 million, making it the most expensive movie of its time. Knowing he needed to drum up widespread interest in his overpriced picture, Wayne hired a Texas PR expert named Russell Birdwell to plug his film. The results were a bit . . . extreme. Before working for Wayne, Birdwell had promoted films like Gone with the Wind and Howard Hughes’s infamous Western, The Outlaw. For the 1939 Civil War epic, Birdwell staged a nationwide search for an actress to play Scarlett O’Hara. This drummed up massive amounts of publicity for the film, and 1,500 actress tried out for the part over three years. When it came time to promote The Outlaw, Birdwell was the man responsible for the famous pin-up photos of Jane Russell in a cleavage-baring top. Simply put, Birdwell (dubbed “the P.T. Barnum of advertising“) didn’t believe in subtlety, and he went all-out to promote John Wayne’s new film. For example, Birdwell claimed that the actual battle of the Alamo was the most important event since “they nailed Christ to the cross.” According to Texas Monthly, Birdwell petitioned Congress to award the Medal of Honor to all the Alamo defenders. He even wanted England, France, the US, and the USSR to hold a summit at the titular San Antonio mission. Topping it all off, Birdwell compiled a nearly 200-page press kit—nicknamed “The Bible”—which listed an impressive set of numbers in order to wow audiences. The book listed how much coffee the crew drank (510,000 cups), how many new roads were laid on set (23 kilometers [14 mi]), how many Spanish tiles were brought in (2,800 square meters [30,000 ft2]), and how much ice cream was consumed (900 gallons). Birdwell’s methods were big, loud, and gaudy, much like Wayne’s film. However, while Birdwell certainly got people’s attention, not everyone was pleased with his tactics. According to Happy Shahan, “Birdwell was Wayne’s doom.”

2 Chill Wills’s Oscar Campaign

After John Wayne shouted “cut” for the final time, the score was composed, and all the scenes were edited together, The Alamo was released in 1960. At its initial screening, Wayne realized that the film was too long and snipped out 40 minutes of footage. Unfortunately, when the film finally reached audiences, critics tore it to pieces. That didn’t stop Wayne and Birdwell from promoting their Alamo monster. The Duke hoped that if the movie could win a few Oscars, then perhaps it would give the film some traction and allow The Alamo to recoup its overblown budget. During Oscar season, Wayne and Birdwell made it clear to Academy voters that if they voted against the film, well, they weren’t good Americans. Wayne’s intense lobbying eventually paid off, and The Alamo was nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture. (In true Oscar fashion, the Academy overlooked worthier films like Psycho.) It was probably painful for Wayne that he was snubbed for Best Actor and Best Director, but at least there was always Chill Wills. A Texas character actor who appeared in films like Giant, Meet Me in St. Louis, and the Francis the Talking Mule series, Willis was nominated for Best Supporting Actor for his turn as Beekeeper, one of Davy Crockett’s hard-drinking but goodhearted sidekicks. Suspecting that this might be his only chance to win an Oscar, Wills hired his own PR manager, W.S. “Bow-Wow” Wojciechowicz. Much like Birdwell, Bow-Wow believed in over-the-top tactics. For example, he took out an ad listing the name of every single Academy member alongside a picture of Chill Wills. Next to the photo, there was a little caption that said, “Win, lose, or draw, you’re my cousins, and I love you all.” This prompted comedian Groucho Marx to take out his own ad which read, “Dr. Mr. Chill Wills, I am delighted to be your cousin, but I voted for Sal Mineo.” However, Bow-Wow wasn’t finished yet. Against all sound logic, he took out an ad in The Hollywood Reporter (without the knowledge of Wayne or anyone who’d worked on the film) that proudly proclaimed, “We of The Alamo cast are praying harder than the real Texans prayed for their lives in the Alamo for Chill Wills to win an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor.” As you can imagine, this did not sit well with Academy members, and it made John Wayne furious. Hoping to get a lid on the situation, the Duke took out his own ad in Variety, explaining that Wills was completely out of line. “I refrain from using stronger language,” Wayne wrote,” because I am sure [Wills’s] intentions are not as bad as his taste.” Wills wasn’t pleased with Bow-Wow, either, and fired his PR manager, but it was too late to rescue his Oscar night dreams. When the Academy voted on their choice for Best Supporting Actor, they went with Peter Ustinov for his performance in Spartacus. In fact, The Alamo only won a single Oscar that night, and it was for Best Sound. As for the category of Best Picture, Wayne’s period piece was defeated by Billy Wilder’s brilliant comedy, The Apartment. It was an ignominious end to a glitzy night, and The Alamo cast was forced to go home in defeat.

1 Remember The Alamo

Of course, at the end of the day, Hollywood is all about money. It doesn’t matter if a film is savaged by critics if it makes big bucks at the box office. So how did The Alamo fare with mainstream audiences? As it turns out, the movie did surprisingly well. It was one of the top 10 grossing films in the US in 1960, and while it was banned in Mexico, The Alamo packed theaters in countries like England and Japan. Just because the picture was doing well didn’t mean Wayne was making any money, however. After all, The Alamo had gone massively over its budget. As previously mentioned, the man had heavily invested in his own film, mortgaging his own homes and film company, and now the Duke was in the red. “The picture lost so much money,” Wayne once said, “I can’t buy a pack of chewing gum in Texas without a co-signer.” In fact, Wayne was in so much financial trouble that he was forced to sell his share of The Alamo to United Artists in order to cover costs. This all came about at a pretty bad time for Wayne. In addition to The Alamo’s massive failure, his financial adviser had made some rather awful investments. Then, Ward Bond, one of Wayne’s best friends, passed away from cancer. These numerous disasters sent Wayne into a depression, but you can’t keep a movie star down for long. Wayne continued making popular movies, cementing his reputation as a legend, and even won Best Actor for 1969’s True Grit. Eventually, the state of Texas even declared Wayne an honorary Texan. As for the film itself, United Artists has rereleased the film enough times to see a profit. As for the set, the Alamo Village appeared in several other films and also operated as a tourist attraction before it was closed in 2010. Despite all the setbacks, disasters, wrecks, rattlesnakes, and rotten reviews, Wayne never turned his back on The Alamo. The Duke was always proud of his movie, even though history has labeled his film a failure. After all, as his Alamo co-star Linda Cristal once explained, “John loved The Alamo as a man loves a woman once in a lifetime—passionately.” Nolan Moore is a writer and editor from Texas. He’s also a big-time movie lover and John Wayne fan (although he doesn’t care for The Alamo). If you want, you can friend/follow him on Facebook or send him an email.